‘The Big Bill Broonzy Story’: A Captivating Tale Of The Blues

Recorded across several intimate sessions, ‘The Big Bill Broonzy Story’ remains an enduring monument to the man who bridged urban and rural blues styles.

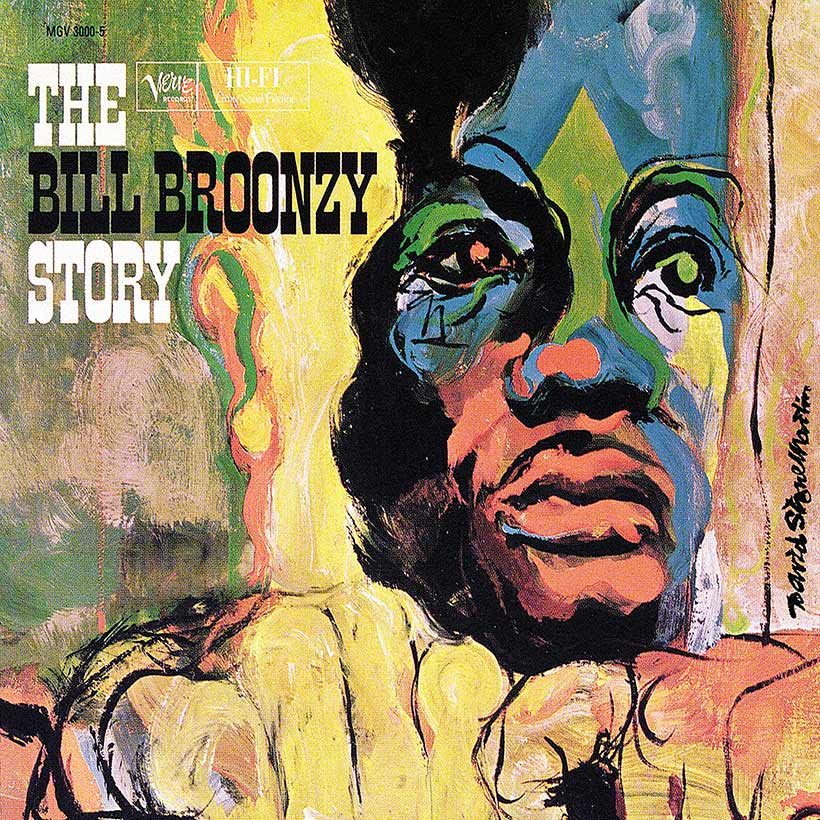

It’s the midnight hour on Friday, July 12, 1957, and blues legend Big Bill Broonzy, 64, is ensconced in a Chicago recording studio laying down tracks for what will become a mammoth 5LP box set released as The Big Bill Broonzy Story on Verve’s Folkways imprint. There’s no band behind Broonzy – rather, it’s just him with his acoustic guitar sitting in front of a lone microphone. Beside him is producer Bill Randle, and behind the glass-fronted control room is the shadowy figure of a recording engineer.

Listen to The Big Bill Broonzy Story on Apple Music and Spotify.

Randle was a noted American folk historian and his rationale for bringing Broonzy into the studio was simple, as he wrote in the liner notes for The Big Bill Broonzy Story: “[It] was to preserve as much of the blues complex as he was able to give us.” Given that Broonzy – an articulate raconteur, despite being illiterate until his later years – came across like a walking history book of the blues, and had known the idiom’s early pioneers who were long gone, Randle’s passion for undertaking the project was wholly understandable. Broonzy’s life, too, was a fascinating and colorful one, and had taken him on an extraordinary journey from the cotton fields of the American south to European concert halls.

Born in 1903, in Scott, Mississippi, and raised in Pine Bluffs, Arkansas, William Lee Conley Broonzy was one of 17 children born to impoverished, sharecropping parents who were former slaves. He worked as a plow hand on a farm from the age of eight, but when he wasn’t toiling in the fields he could be found playing a crudely-constructed box fiddle, which he quickly became proficient at, performing for small change at segregated picnics.

In 1920, after a spell in the army, Broonzy ventured north to Chicago. There he hooked up with early blues pioneer, Papa Charlie Jackson, switched from fiddle to guitar, and began his career as a musician. With his smooth but strong voice accompanied by dexterous guitar playing, Big Bill Broonzy was soon impressing people with his urban-inflected country blues, and then cut his first record, in 1927. He recorded under a variety of guises in his early years – Big Bill And Thomps, Big Bill Johnson, Big Bill Broomsley, to name a few – and in 1938 appeared at New York’s prestigious Carnegie Hall (which up until that point had been exclusively a classical music venue) in the famous From Spiritual To Swing series of concerts organized by legendary A&R man and talent spotter John Hammond.

Broonzy wasn’t a convert to the electric blues style that emerged in Chicago in the 50s, but continued to ply his trade in an acoustic setting, which resulted in him being largely perceived as a folk musician. It was a period when, despite his approaching twilight years, he traveled abroad and was playing to packed venues throughout Europe.

A sprawling quintuple LP, released on April 17, 1961, The Big Bill Broonzy Story came at a time when there was an explosion of interest in blues and folk music from predominantly white audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. Producer Bill Randle just put Broonzy in front of a microphone, gave him a whiskey, and rolled the tape. They recorded for three hours and then had two more follow-up sessions. The vibe on all of them was informal and relaxed, with Broonzy interspersing his performances with spoken reflections on his life and anecdotes concerning the many musicians he had known. What results is a deeply fascinating oral history of Broonzy’s life – significantly, it also paints a vivid picture of life for African-Americans during the early part of the 20th Century.

Randle gave Broonzy a free hand in choosing his material for the album, which included two of his most famous songs, “Key To The Highway” and “Southbound Train.” He also featured “Tell Me What Kind Of Man Is Jesus” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” to illustrate his roots in African-American spiritual music. He also paid tribute to fellow blues mavens Bessie Smith, Tampa Red, and Leroy Carr – the latter described by Broonzy as “one of the greatest blues writers I’ve ever known” – with heartfelt renditions of their songs.

It’s hard to believe that Broonzy’s voice – with its clear articulation, rich timbre, and soulful vitality – was silenced not long after the album was made. In fact, the day after the third recording session for The Big Bill Broonzy Story, Broonzy went into hospital to undergo surgery for lung cancer. By April 1958, the singer was seriously ill and required another operation, this time on his throat, which, tragically, took away his ability to sing. Just over a year after The Big Bill Broonzy Story was recorded, its creator was dead, passing away on August 15, 1958, at 5.30am.

Often described as Big Bill Broonzy’s last will and testament, The Big Bill Broonzy Story remains an enduring monument to a man whose singular style was the bridge between rural and urban blues styles.

Lucien Stark

October 23, 2019 at 12:21 am

Well all I can add is he got the last clean shirt

Tony Thomas

August 7, 2021 at 7:50 pm

Recent scholarship suggests that this one of many reinventions Broonzy made of himself to market himself as a commercial performer. It comes in the period when he marketed himself as a “folk blues” performer largely because the Blues he cranked out in Chicago ultimately as the main main in Lester Melrose’s stable of blues artists mainly feeding into RCA Victor’s Bluebird records. By the late 30s, Broonzy was perfrming more and more in what could only be seen as a jazz combo often with horns and had dropped his acoustic guitar for an electric guitar. Curiously, though Broonzy began as a fiddler and didnt fully learn guitar until Chicago, the jazz recordings gave him license to play the violin he always carried with him throughout his career. This kind of show was epitomized by Broonzy’s performance in the Spirituals to Swing concern in 1938 at Carneige Hall. There Bill who had lived in Chicago since 1920, appeared in overalls, claiming to have stepped out of the cotton fields of Arkansas and played a few tunes and said he had to get back, when he in fact lept into his Cadillac to drive back to Chicago to play at a Christmas party for Tampa Red, I believe, and other stars of Melrose stable. Broonzy was the product of the great music the professionalization of Black blues singing, guitar, and ensemble leadership that came in the late 1920s and 1930s and early 40s. I am not down grading his “folk blues” but this was what Broonzy found a way to do when his music was superceded by newer folks like Muddy Watters. I adore his folk blues and folk singing as the best he could do, but the music he

Lance Jablonski

April 19, 2022 at 5:34 pm

Best thumb in the business!