Best Yusuf / Cat Stevens Songs: 20 Peaceful Pop Hits

The lyrical honesty and varied instrumentation of the singer-songwriter makes for great songs that are far more complex than first meets the ear.

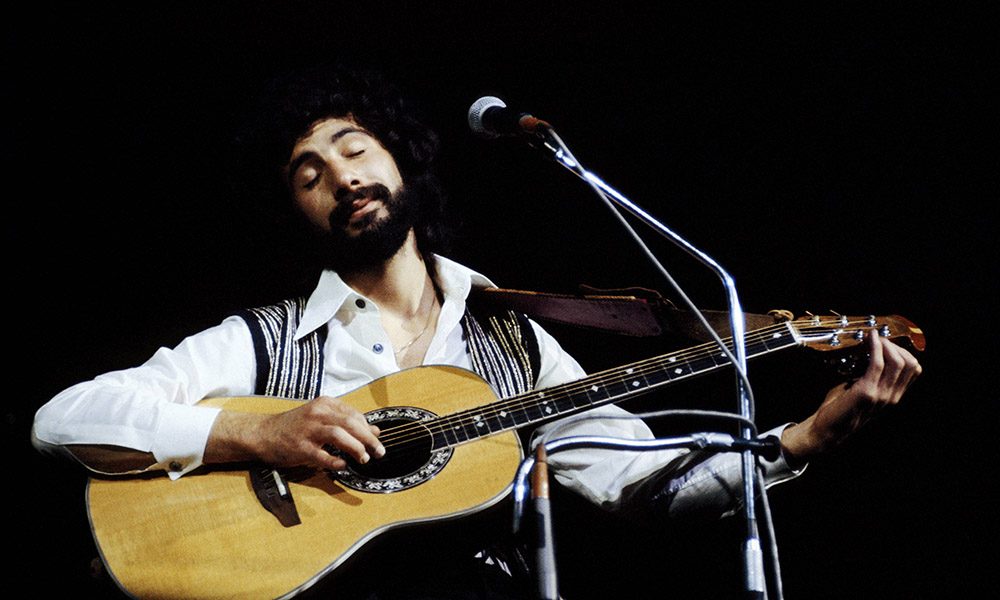

Although he’s best known as a rosy-eyed, hippie-era guitarist, Yusuf / Cat Stevens’ lyrical honesty and varied instrumentation are far more complex than first meets the ear. His voice – at times twangy, at others soft and sincere – fits seamlessly with booming choruses and gentle missives alike. Mired in the vision of a peaceful future but clouded with worry at what’s to come, Yusuf’s music comforts and frets in equal measure.

To call Yusuf solely a singer-songwriter would ignore his penchant for orchestration and grandeur, heights that sit alongside his gentle, folk tunes. He’s also had a hand in hits beyond his own: before he broke through as an artist, he wrote both “Here Comes My Baby” and “The First Cut is the Deepest.”

Cat Stevens left his music career behind in 1977 when he converted to Islam, taking on the name Yusuf Islam. In 2006, he returned to the studio, after which he released 2006’s An Other Cup, 2009’s Roadsinger, and 2014’s Tell ‘Em I’m Gone. In 2014, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and has continued to release music. In 2020, for instance, he recasted his 1970 classic Tea for the Tillerman.

Listen to the best Yusuf / Cat Stevens songs on Apple Music and Spotify.

Existential Eulogies

(“Wild World,” “Father and Son,” “I’ve Got a Thing About Seeing My Grandson Grow Old,” “Oh Very Young,” “Dying to Live”)

Yusuf’s songs always want the best for their addressee, and that steeps them in sentiment: each track advises and frets, often accessing a wisdom far beyond his age at the time of writing. He wrote both “Wild World” and “Father and Son” around age 22. Two of his most famous tracks, they’re cautionary and fearful – the narrator realizes he may not be able to guide or stay with others forever. “Wild World” recounts his uncoupling from actress Patti D’Arbanville, whereas “Father and Son” was originally created for a musical set during the Russian Revolution – this project was halted when he contracted tuberculosis. When it was later released, many felt it highlighted the divide between generations. The fact that “Wild World” is ostensibly a breakup song and “Father and Son” appears familial, is of no importance: both tracks are driven by empathy, by wanting the best for others after you’re gone, saddled with the awareness that it may not be possible.

“Oh Very Young” is preoccupied with intangibility: a person slipping through your fingers and what they leave behind, especially when they pass young. “I’ve Got a Thing About Seeing My Grandson Grow Old” finds the narrator taking care of himself, motivated to stay alive so he doesn’t miss out on the future.

Yusuf ruminates existentially to some degree on all these songs, but none so explicitly as “Dying to Live.” Across a pseudo-jazzy piano track, an isolated man wonders about life’s purpose and meaning.

Aspirational Anthems

(“Sitting,” “If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out,” “Can’t Keep It In,” “Hard Headed Woman”)

Sometimes, Yusuf’s enthusiasm bursts out into the open; he quite literally “Can’t Keep It In.” It’s hard not to smile just a little bit when you hear the lyrics “I gotta show the world, world’s gotta see / See all the love, love that’s in me” sung out loud. It’s not hamfisted because it’s sincere. On these songs, he’s nearly shouting. But warmly, with excitement. On “Sitting,” he imagines success from the outset (“Oh, I’m on my way, I know I am”) and offers a unique way of imagining that optimism (“I feel the power growing in my hair”).

These songs seem made for the sake of singing: you could compare them to the “I Want” songs of musical theater. Just listen to “If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out” (which also appears on Harold and Maude) – the title says it all. Whether it’s joy he wants to express or possess (“Hard Headed Woman” is an ode to the type of motivating lover he craves), Yusuf’s aspirational anthems reverberate with personal yet universal ambitions.

Religious Reckoning

(“Morning Has Broken,” “King of Trees,” “The Wind,” “Miles from Nowhere”)

Even before Yusuf’s conversion to Islam, he was ruminating on the world. “Morning Has Broken” is originally a Christian hymn. An ode to nature, the imperative “praise” asks listeners to jointly experience that first morning light, that first blackbird singing: the idea that every new day is a new birth of the world. The natural wonder is even more apparent on “King of Trees,” where synths and keyboards open on Yusuf praising nature’s majesty and resilience, even as humans threaten to destroy it.

“The Wind” is more introspective. Over fingerpicked guitar, Yusuf listens to the “wind of his soul”; he admits to “[swimming] on the Devil’s lake” but says he’ll “never make the same mistake.” “Miles From Nowhere” takes religious reckoning into practice: it’s all about the journey. Each time the song builds up from the verse, he cries: “Lord, my body has been a good friend / But I won’t need it when I reach the end.” His preoccupation with death is immaterial when religion enters the song: there’s conviction, always, even when it’s not clear what that belief is.

Choral Crooners

(“Peace Train,” “Tea for the Tillerman,” “Moonshadow”)

Yusuf has never been afraid to bring in a traditional chorus for his songs, and they always usher in joy. “Peace Train” – his first Top 10 US hit – rolls on the wheels of its backing voices, bolstered by their reverential, outstretched arms. His optimism shows most clearly on these songs. The group vocals naturally signal unity and community – that positive hippie vibe he’s most often associated with.

The choral effect is a bit different on decidedly brief “Tea for the Tillerman,” where group vocals don’t work throughout the song as an echo, but instead serve for a dramatic end. The track starts out with soft piano, Yusuf’s vocals ambling forward. It speeds into the euphoric phrase “happy day,” and that’s where the choir flows in; the homonymous album closes out on a very quick, joyous note.

“Moonshadow” alternates between sloping, quiet verses that praise nature and more jubilant choruses wherein he offers himself up to this beauty, no matter the price. The choir backing on this song is most reminiscent of folk tradition: the voices join him with full strength for the final chorus.

Mournful Moments

(“Trouble,” “Sad Lisa,” “Where Do the Children Play,” “Maybe You’re Right”)

Yusuf often wavers between optimism and pessimism in his songs. Sometimes, though, they’re more fully dejected. “Trouble,” for instance, was written after a year of convalescence, when at 19, he was hospitalized and expected to die. It marinates in sorrow. (You may have heard it in Harold and Maude, where it plays before Maude’s death.)

“Sad Lisa” is similarly sullen. Like his sentimental family songs, it focuses on a person he wants to save, its piano reminiscent of a lullaby. On the same album, “Where Do the Children Play?” also worries for others’ wellbeing. However, it’s more concerned with consumerism and capitalism – and, by extension, our general sense of wellbeing amid “progress.”

Always one to reason through feeling, “Maybe You’re Right” analyzes then tries to move on from a breakup. The narrator sees both sides. But still, desperation surges: “So tell me, tell me, did you really love me like a friend? / You know you don’t have to pretend / It’s all over now, it’ll never happen again.” With that admission, he comes to terms with it, repeating like a mantra: “it’ll never happen again.” At the end, he’s circled back to where he began: it’s anyone’s blame and both their regrets.

Did we miss one of the best Yusuf / Cat Stevens songs? Let us know in the comments section below.

Amit Sen

December 4, 2020 at 9:07 pm

“Into White”, “Fill My Eyes”, “Lillywhite”, “Katmandu”, “18th Avenue”, “Sweet Scarlet”

German Rosas

March 11, 2021 at 5:43 pm

I think the song about the breaking with Patti D’arbanville is “My Lady D’arbanville”, not “Willd World”, s song Cat Stevens wrote about himself.

Thanks.