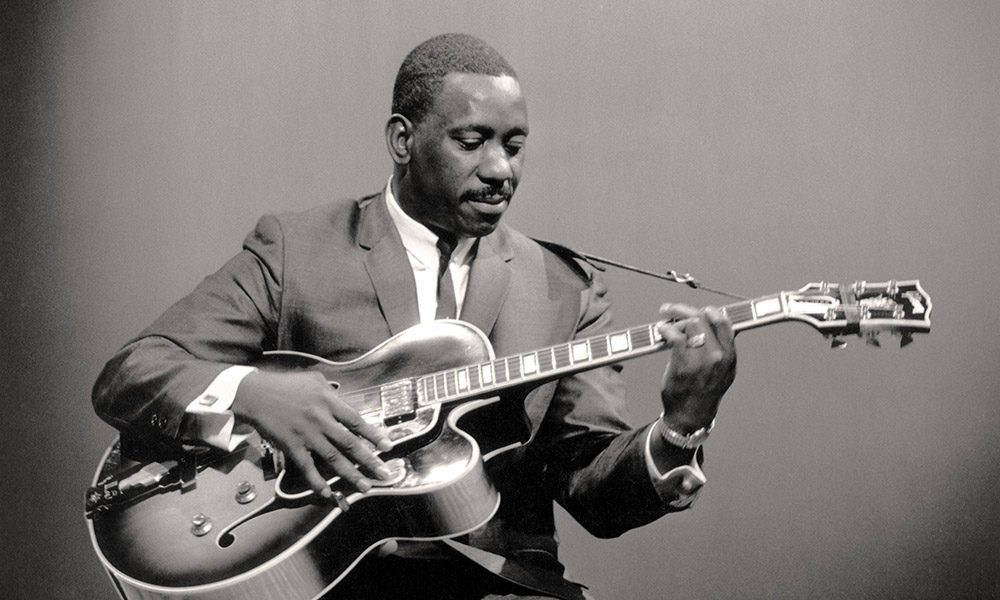

Best Wes Montgomery Pieces: 20 Jazz Essentials

Decades after his death, Wes Montgomery’s keen ears and boundless imagination still bowl over jazz aficionados and newbies alike.

If jazz seems too impenetrable and intimidating to get into, dig this. Wes Montgomery, arguably its greatest guitarist, couldn’t read music, didn’t know theory, and didn’t understand his instrument’s electronics. He also strummed exclusively with his thumb, an idiosyncrasy that would make any music instructor run faint. But with the possible exception of Jim Hall, any jazz guitarist with an iota of self-awareness genuflects to him as the greatest to ever do it. Decades after his death, his keen ears and boundless imagination still bowl over jazz aficionados and newbies alike.

“You know, I love Grant Green,” says guitarist and instructor Mike Pachelli, plucking one of that celebrated guitarist’s riffs. “But try playing it in octaves. It’s extremely difficult, and nobody was doing that. That just did not exist when he did it. He was able to play that stuff at the same speed that Kenny Burrell or Grant Green could play single-note lines.” Wait. Pause. If Montgomery could play as nimbly and ably as those guitar pioneers, but with every note matched with its octave partner, wouldn’t that make him twice as good as those revered players?

“He was a hundred times better,” Pachelli says. “And if they’re honest, they’re saying the same thing. All of us who play jazz – and I only attempt to play jazz – we’re not even in the same hemisphere as this man. He was a naturally talented genius who was born to do this.”

Listen to the best Wes Montgomery pieces on Apple Music and Spotify.

Until he received his first guitar at 12 and began seriously practicing at 19, Montgomery was seemingly destined to be a nobody. His gateway was Charlie Christian, arguably the first famous electric guitarist. “I liked Django Reinhardt and Les Paul and those cats, but it wasn’t what you’d call new,” Montgomery recalled to DownBeat in 1961. “He was it for me, and I didn’t look at nobody else. I didn’t hear nobody else for a year or so.”

While Montgomery woodshedded Christian’s solos, the neighbors’ noise complaints compelled him to drop the plectrum and play with his thumb. The resulting plummy sound became his lifelong trademark. After only two months of practice, his playing caught the ears of a passing club-owner, and he was so impressed that he knocked on Montgomery’s door. One thing led to another, and Montgomery began gigging around his hometown of Indianapolis, copying Christian solos. His work on the club circuit led to his first big break: a brief stint on the road as part of the Lionel Hampton Orchestra.

In the six years after returning to Indianapolis, after clocking out at one of his several blue-collar day-jobs – at a battery factory, a cafeteria, or a dairy – he gigged in the evenings. In 1955, he began playing regular local gigs with his brothers, pianist-vibraphonist Buddy and bassist Monk. And that’s what defines the first era of Montgomery’s career: fraternal rapport.

The Montgomery Brothers

Montgomery’s run with Buddy and Monk roughly began and ended when the 1950s did. The trio released a handful of records as the Montgomery Brothers – and, later on, in the Mastersounds. As an introduction to this period, check out “Wes’ Tune” from 1958’s Montgomeryland (later reissued as Far Wes).

“That’s Wes playing rhythm changes, but with Wes’s chromatic language and reharmonizations on the bridge,” explains jazz guitarist Kenny Wessel. Decoded for non-musicians: Montgomery took the totemic chord progression to George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm” – rhythm changes – and applied his innovative, personal harmonic approach.

After you’ve digested “Wes’ Tune,” check out the bluesy title track to 1961’s Groove Yard – a Carl Perkins tune – and Buddy’s loose, mellow original “Beaux Arts” from that year’s The Montgomery Brothers in Canada.

Early leader albums

In 1959, the alto great Cannonball Adderley caught Montgomery at the Missile Club in Indianapolis. “Cannonball moved to a table in front of Montgomery, who was already showing his marvelous, unique technique. The next memory I have is that Cannonball leaned way back in his chair as if knocked out – which he evidently was,” photographer Duncan Schiedt later said. “He stayed rooted to his table all the time I was there.”

Upon returning to New York, “Cannon’s brief monologue in my office ran something like this: ‘There’s this guitar player in Indianapolis, and we’ve got to get him for the label!’” Riverside Records’ A&R director Orrin Keepnews said in the liner notes to Montgomery’s The Complete Riverside Recordings. “My immediate reaction was to want to hear for myself.”

Keepnews got on a plane from New York to Indianapolis and caught Montgomery at his frequent haunt, the Turf Bar. “I was able to get a bar stool almost directly in front of Wes, and it was only a matter of seconds until I realized I was listening to something truly different,” he recalled. “The thumb [moved] so fast on the first uptempo number that it literally blurred before my eyes.”

He bought Montgomery out of his contract with Preside Records for $108. Two weeks later, Montgomery, organist Melvin Rhyne, and drummer Paul Parker traveled to New York and recorded 1959’s not-bad A Dynamic New Sound: Guitar/Organ/Drums.

Montgomery as a leader really gets started with his second album, 1960’s The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery, with pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Percy Heath, and drummer Albert Heath. “West Coast Blues” contains everything quintessentially Wes – a big sound, a soulful groove, and a trademark solo structure that he’d repeat throughout his career.

“I don’t think he invented it, but I think he sort of codified this arc of the solo, which is to start with single lines, then to go octaves, then go to block chords,” Wessel says. “There was a built-in dramatic arc of the solo where it would get denser harmonically.”

Also must-hears: the simmering, percolating originals “D-Natural Blues” and “Four on Six,” his tender version of Dave Brubeck’s “In Your Own Sweet Way,” and his exquisite version of the standard “Gone With the Wind,” which Wessel calls “a masterclass in solo architecture in jazz guitar playing.”

“While We’re Young” also has a gorgeous solo performance from 1961’s So Much Guitar!, which features pianist Hank Jones, bassist Ron Carter, drummer Lex Humphries, and percussionist Ray Barretto.

With the Wynton Kelly Trio

In 1961 and 1962, Montgomery briefly joined John Coltrane’s quintet with multi-reedist Eric Dolphy, pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Reggie Workman, and drummer Elvin Jones. This collaboration proved to be a nonstarter. “He didn’t feel intimidated by the people in the band, but I think he was a little uncomfortable with some of the things that were happening musically,” Tyner told JazzTimes in 1995. “Maybe he felt like he couldn’t contribute to that. Whether he could have moved with us to the next conceptual stage is maybe questionable.”

At any rate, Keepnews then decided to capture Montgomery in comfortable settings with Miles Davis’s rhythm section – pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Jimmy Cobb – then considered the best in the business. The musicians recorded 1962’s Full House at the Tsubo club in Berkeley, California, with tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin. The album is a must-hear from beginning to end, but the bluesy, confident title track and the head-spinning “Blue ‘N’ Boogie” are outstanding.

“I’m not being facetious,” Pachelli says. “You can take four measures of a song like ‘Blue ‘N’ Boogie and spend the rest of your life on those four measures.”

Full House acts as an on-ramp to the ultimate Montgomery album: 1965’s Smokin’ at the Half Note, also with the Wynton Kelly Trio. “There wasn’t a tighter piano-bass-drum combination in jazz,” claims alto saxophonist Jim Snidero. “Wes jumped in the driver’s seat, and that was it. Magic.”

About the opener “No Blues”: “That’s a brilliant solo and a long development of great blues lines,” Wessel says. “That’s another masterpiece.” Montgomery’s solo on “If You Could See Me Now,” meanwhile, may make your heart leap into your throat. Pat Metheny didn’t call it “the greatest guitar solo ever played” for nothing. And there’s also the epochal solo on Sam Jones’ “Unit 7.” Quite simply, Snidero says, you can boil down this enchanting date to one repeated word: Swing, swing, swing!

Collaborations with organists

1963’s Boss Guitar may be the fourth- or fifth-best Montgomery album, but it displays two critical aspects of his art: his knack for extracting beauty from so-so material and his rapport with organists.

“He took some tunes that weren’t that great, like ‘Canadian Sunset,’ and made them so hip,” Wessel says. “Days of Wine and Roses,” another subtle, romantic ballad, benefits from Melvin Rhyne’s organ as aural glue. “For Heaven’s Sake” is languid and lovely enough to lower your blood pressure.

Although little information exists about their musical rapport, Montgomery’s two team-ups with Hammond B-3 master Jimmy Smith, 1966’s Jimmy and Wes: The Dynamic Duo and Further Adventures of Jimmy and Wes, are exceptional, swinging records. Start with “Night Train” from the former and “King of the Road” from the latter.

Strings and pop covers

Orchestral albums unfairly get a bad rap in the jazz world, but they can be transcendent; Charlie Parker’s astonishing With Strings is Exhibit A. Montgomery’s 1963 album Fusion! Wes Montgomery With Strings displays what he could do with an orchestra.

Montgomery turned up the commercial appeal with his final run of albums on producer Creed Taylor’s label CTI; the results sold well and made him his first real money. While the rococo string arrangements may be a bit much for some, Montgomery’s playing is first-rate. Check out how he wrings soul from the Beatles’ despondent “Eleanor Rigby,” from 1967’s A Day in the Life.

Montgomery died of a heart attack in 1968 at only 45. But jazz musicians are still transcribing and studying him, and he gave the rest of the world a lifelong toe-tapping experience.

“Unfortunately, Wes left us way too early. He was one of the most consistent jazz artists in history,” Snidero says. “For me, Wes was the epitome of the hard-bop movement. His music was highly arranged, incorporating his innovative block chord technique for Basie-like shout choruses. He favored a lot of gospel themes, balancing that earthiness with sophisticated bebop language. That’s hard bop.” Whatever you call Montgomery’s playing, we’re not likely to see the likes of him again.

Think we missed one of the best Wes Montgomery pieces? Let us know in the comments below.

Robert Cobb

March 7, 2021 at 11:34 pm

Wes is my Favorite and his ability to express songs of many eras is so cool.

Gus Chunkman

January 31, 2022 at 9:40 pm

Good list, but you could have replaced the tunes from the “Day In The Life” lp with more tunes from the “Down Here On The Ground” lp.

Martin jourard

June 15, 2022 at 6:27 pm

I’ve listened to most of Wes’s recorded output and to my ears, his solo on “Mr. Walker,” the trio version with the Heath brothers on bass and drums, has Wes’s most intriguing and structurally perfect solo.

David Rinehimer

March 8, 2023 at 2:54 am

Caravan – arranged by Oliver Nelson. So driving and melodic.

Myron Apilado

March 8, 2023 at 4:14 pm

Wonderful…..just that!