The Best Camarón de la Isla Songs: 15 Revolutionary Flamenco Tracks

The singer’s voice was rooted in the historic laments of the diverse marginal communities that came together in Spain. It created nothing less than a revolution in song.

There’s one word commonly associated with Camarón de la Isla’s voice: goosebumps. Others call it simply “the Camarón effect.” Young, old, gypsies, non-gypsies, and, at this point, several generations of Spanish and global fans regard Camarón as the greatest flamenco singer of all time. Flamenco experts have deemed his singing “the call of life and of death,” and his instrument “God’s throat.”

Born José Monge Cruz in 1950, the singer attracted immediate attention in San Fernando, his hometown in Southern Spain, when he started singing publicly at no more than kindergarten age. It was in the 1970s that he would change the sound of flamenco and become an idol for the masses; flamenco’s forever rock star.

Listen to the best Camarón de la Isla songs here.

Decades after his premature passing at age 41, Camarón is a musical beacon for young artists from the reggaeton generation, most famously Rosalia, and a Spanish popular hero. Without him, flamenco would not have so powerfully transcended the confines of classification as a folkloric “world music” genre. The indescribable voice of Camarón made a sound rooted in the historic laments of the diverse marginal communities that came together in Spain, creating nothing less than a revolution in song.

The gypsy songbook

Camarón de la Isla was one of eight children born into a Romani family in Spain’s Cadiz region, the cradle of flamenco. He got his nickname early – he was called “shrimp” because of his slightness, and his light hair and complexion, that could seem almost transparent next to his family members. Like other flamenco artists, the name was connected to his city of origin: San Fernando is located on la isla de León (León Island).

José’s voice was already known to neighbors when he started going to La Venta de Vargas, a restaurant where he first heard great singers like Manolo Caracol, who became a mentor. By age eight, he was singing there himself. Today, it’s a shrine to his memory.

The album Camarón – Venta de Vargas is an incredible time capsule. Here, you can hear Camarón’s voice in pure form as an adolescent, accompanied on songs by guitar, handclaps, foot shuffles, clacking plates, patrons talking, and even crickets. Raw and joyous on tracks like “Azucar Cande” and “Amante de Abril y Mayo,” this compilation is a testimony to Camarón’s innate talent and enthusiasm for his art, before his voice deepened and his soul darkened, relishing in the rhythms that were his birthright.

In later years, when he had begun to experiment with new fusions, Camarón would be accused of betraying the authentic essence of flamenco. This album serves to confirm what the singer said in an interview with Spanish television interview that has been quoted like gospel by flamenco fans: “If what is inside of you is truly pure, you will never lose it.”

The magical duets with Paco De Lucia

From the moment that Camarón de la Isla met guitarist Paco de Lucia in a Madrid flamenco club, they were inseparable. Their relationship, as suggested by the stark title song of their second collaborative album, 1970’s Cada vez que nos miramos (“Every Time We Look at Each Other”), could seem telepathic. On that album’s cover, the singer stands facing the guitarist under a fiery Andalusian sky.

The first albums, starting with 1969’s Al verte las flores lloran (The Flowers Cry When They See You), highlights the budding guitar genius of De Lucia and Camarón’s unmistakable vocals in a classic flamenco style. Camarón and Paco riffed on standards, and music and lyrics composed by some of the genre’s most popular artists. On the track “Que un toro bravo en su muerte,” Camarón starts to unspool the emotion that would characterize his career: Cue the goosebumps.

Those first albums, released on cassette, were quickly noticed in working-class neighborhoods in Cadiz and Sevilla, and particularly by teenagers, who would soon begin to copy Camarón’s musical style, but also his dress and mannerisms. It was 1981’s “Como el Agua,” however, that became their first big hit, a lighthearted Spanish road trip evergreen that portended what was to come, for both Camarón and flamenco.

The legendary album

In 1979, four years after the death of dictator Francisco Franco, Spain was becoming a new world, and Madrid was its cork-popping cultural capital. With the guitarist Tomatito taking the place of De Lucia at Camarón de la Isla’s side, and a cast of Spanish musicians weaned on flamenco but enamored by Jimi Hendrix, Camarón ushered in the age of flamenco rock with a musical fusion that brought electric guitar, drum kit, and sitar into the mix.

It was Camarón’s tenth record. La Leyenda del Tiempo, a concept album whose lyrics adopted poems by Federico Garcia Lorca, inaugurated a new era for flamenco, perhaps best represented by “Volando Voy” – an anthem for a freewheeling modern lifestyle written by rocker Kiko Veneno.

Like other revolutionary records, it was met with disdain from critics and alienated fans, some of whom returned it to the store, decrying it as music for hippies. But it later became a cult hit, particularly prized by musicians for its weaving of rock and jazz with flamenco. A writer for one Spanish newspaper summed up its effect simply as “the album that taught us to be free.”

The chartbuster

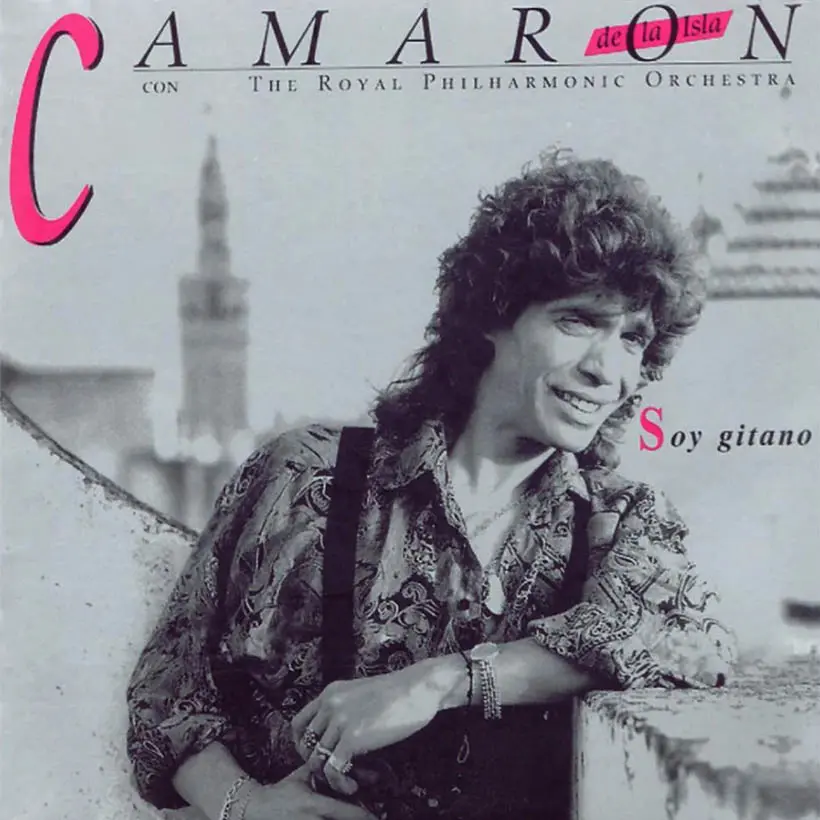

By 1989, Camarón de la Isla’s star was shining in mainstream circles, and his next album would be a major production, complete with a fashion-forward photo shoot and a recording session at Abbey Road studios. On “Soy Gitano” (“I Am a Gypsy”), the Spanish icon is backed by London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. That may have started out as a producer’s idea of a gimmick, but Camarón transcended the novelty, and the album earned him his first gold record in Spain.

Camarón had reached iconic status, but one song on the album – given his early death – seems chillingly prescient, “Dicen de mi” (“They Say About Me”).

They say about me,

That time is threatening me,

They say about me

Am I alive or dead

And I tell them I tell them and I say.

While my heart still boils

I will defeat my enemy

The Montreux Jazz Festival Concert

Cheers and applause greet Camarón de la Isla and guitarist Tomatito on the album Montreux 1991, live from the Montreux Jazz Festival. The singer, dressed nattily in a suit with a pocket square, was the main attraction at the famed festival’s flamenco night, a Spanish showcase presented under the slogan “Spain, where new music lives.”

Tomatito’s lush guitar accompanied Camarón on a sampler of traditional flamenco styles, untitled on the album, opening with an alegrías, party music from Cadiz; and including tarantos, the miners song from Almeria, and tango flamenco.

The excited crowd greeted Camarón’s spurts of vocal energy with applause and shouts. But his voice was noticeably hoarse, and his breath at times labored as Tomatito urged him forward onstage, like a jockey encouraging an injured racehorse. An acoustic version of “Soy Gitano,” featuring the full ensemble of flamenco artists who had come for the all-star concert, made for a fantastic “fin de fiesta” for those in the audience. Listening to it today, it sounds like a bittersweet tribute to Camerón himself.

The last songs

Camarón de la Isla’s last album, Potro de Rabia y Miel was released in early 1992, about six months before he died of lung cancer. The album, which had taken 14 months to record, features both of the guitarists who accompanied him in his career and his life, Paco de Lucia and Tomatito.

In this coda, which one Spanish music critic called the singer’s “sonoric will,” the power of Camarón’s voice is in force, returning to his roots and carrying them forever into the future. The songs include “Una Rosa Pa Tu Pelo,” a tribute to his boyhood idol Manolo Caracol. But the title track, featuring a haunting ecclesiastical chorus of voices and handclaps, is an epitomic example of the Spanish blues that Camarón sang like no other.

He died on July 3, 1992, news reported on Spanish television by red-eyed commentators. Over 100,000 mourners attended his funeral, ushering Camarón de la Isla into immortality.