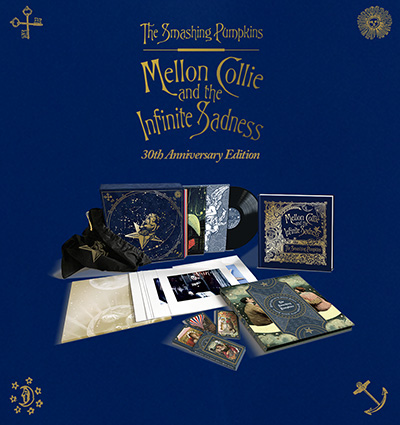

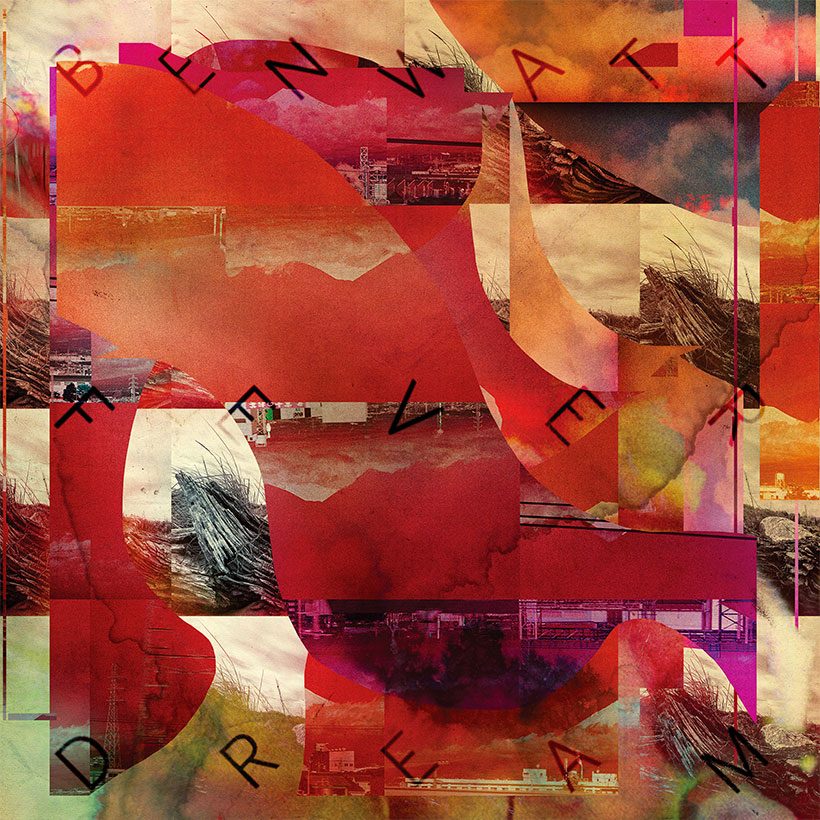

Ben Watt Shines Bright On ‘Fever Dream’

Thirty-plus years into a remarkably wide-ranging career, Ben Watt is ready to release his third solo album, Fever Dream. Like its predecessor, 2014’s Hendra, it sees Watt returning to “words and songs”, and the folk-jazz music he first explored on 1983’s North Marine Drive.

“I understand to a newcomer how my career must seem quite bewildering,” Watt says, going on to précis his work: “My early solo career as an experimental singer-songwriter guitarist in 1982-83, working with Robert Wyatt and Kevin Coyne; then 20 years on the fringes of the pop mainstream with Everything But The Girl, including one huge dancefloor hit; then 10 years as an underground house DJ with an electronic label. Throw in a couple of books, a residency on BBC 6 Music, and then a return to a kind of folk-jazz template and it all must get quite confusing.” He adds: “It’s not a conventional path, but does that matter?”

We’d argue that it doesn’t, particularly when you’re putting out records as good as Fever Dream. With the album due for release on 8 April, we spoke to Watt about this latest step in his astonishingly varied career…

There’s been very little time between Hendra and Fever Dream. Are you particularly full of ideas at the moment?

Having been wrapped up in electronic music for about 10 years, I realised I wanted to get back to words and songs again. It was where I started out back in the early 80s. Once I made the move I realised very quickly what it meant to me: I seemed to reconnect with some kind of nucleus within myself; I felt very motivated. I played 60 live shows with Hendra, my first for many years as a singer and performer. I got stronger every night. When I finished in December 2014 I just wanted to start again. Musically, I love playing live with musicians again: no loops, no computers. Lyrically, I feel in a rich vein at the moment – at the midpoint of my life looking forward and back. It throws up a lot of ideas.

Fever Dream is a wholly apt title. The album conjures being in two states at once: something that’s deeply felt and real, but which is also a bit like seeing things through a gauze… Is that an effect you were going for?

Fever Dream is a wholly apt title. The album conjures being in two states at once: something that’s deeply felt and real, but which is also a bit like seeing things through a gauze… Is that an effect you were going for?

That is a good description; it is exactly the mood I wanted. There is a precision to a lot of the lyrics but also a deliberately impressionistic, elliptical quality to others, to try and capture the way deep thought and dreaming can warp what we think we know and feel. I’ve realised that all thought is a kind of dreaming. When we are lost in thought, we say we are daydreaming: literally, dreaming during the day. I wanted to the album to be clear and unclear, transparent and opaque.

The songs seem to examine one’s intimate moments, yet the album also feels like it would work perfectly as a soundtrack. Does it reflect where you currently are in life?

There have been big turning points lately. Both my parents have died in recent years, as well as my half-sister, unexpectedly. At the same time my kids have grown up and are now teenagers and young adults. And my own personal relationship with Tracey [Thorn] is 35 years old this year… As we grow older we both find ourselves enmeshed in rewarding, complex long-term relationships, but also still aware of own isolated inner selves. I wanted to capture those feelings unsentimentally but also honestly and sympathetically.

You started out in 1983 with North Marine Drive, released on Cherry Red, a label still remembered back then for releasing the 1980 debut album by hardcore punks Dead Kennedys. How did you fit on that roster?

Cherry Red was deeply uncool. But then they took on a new A&R man, Mike Alway, with a remit to change everything and drag the label screaming into the 80s. He drew a line in the sand and signed a broad cross section of experimental underground pop and rock. The experiment exploded within three years and Mike moved on, but I was proud to share a label with new bands like Felt and Marine Girls. It felt like a new vanguard of like-minded souls.

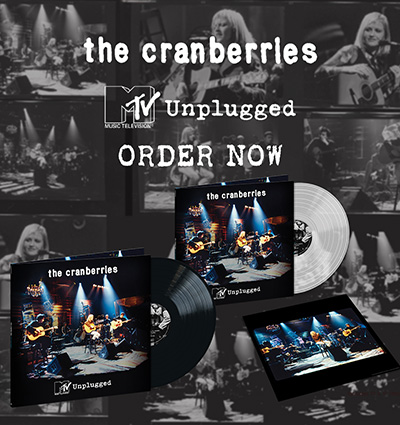

Your Everything But The Girl records have been reissued recently. How do you feel about that part of career, looking back?

Your Everything But The Girl records have been reissued recently. How do you feel about that part of career, looking back?

Good bits, bad bits. You always think you could have done something better. I knew the reissues would happen at some stage, and though neither Tracey nor I are nostalgists, we knew it was better to get involved in them rather than let someone else mess them up. So we tried hard to source interesting additional material and put each one into the context of when it was made: a proper historical document of each album’s respective time, which hopefully deepened people’s appreciation of them.

In an era where bands are reforming on a regular basis, have you and Tracey ever felt the urge to record or perform under the EBTG banner again?

No. Like I say, neither of us are particularly nostalgic. I think that if you are serious about your work, you should be looking to create, not curate, as much as possible. No one expects jazz musicians to play their old albums from start to finish, or painters to re-paint old paintings; we expect new work from them, until they die. Look at the recent Hockney landscapes. Phenomenal. But we reward pop musicians for reproducing their past glories note for note. Isn’t that a bit odd? It puts the power in the hands of the audience, which is not what an artist should really want, is it?

Obviously you’ve written pop hits, masterminded club tracks, have jazzier excursions in your catalogue, have run record labels and published books: how do you keep up with all these ideas?

I always wanted to be a musician and songwriter, to be involved with music. My teacher asked me in front of the class what I wanted to be when I grew up. I was thirteen. I said a rock star or Jacques Cousteau. Everybody fell about laughing. But I don’t feel so different now – the same sense of adventure and need to stand up in front of people and be heard. At heart I am probably just a terrible show-off.

From the names of your labels Buzzin’ Fly and Strange Feeling it seems you’re a Tim Buckley fan. Did he set a “no boundaries” precedent for you?

From the names of your labels Buzzin’ Fly and Strange Feeling it seems you’re a Tim Buckley fan. Did he set a “no boundaries” precedent for you?

I have always loved that jazz-folk template of the late 60s: Tim Hardin, David Crosby, Tim Buckley, Jim Sullivan, Nick Drake. It was one of the first things I really connected with musically. John Martyn was the front door for me as a teenager, and then I worked back into its roots. Perhaps it said a lot about my musical upbringing – my father was a jazz musician and my siblings loved 60s and 70s folk and rock. I just fused the two. I always thought Buzzin’ Fly would be a great name for a label, so when I launched one I chose it, even though it was a house and techno label!

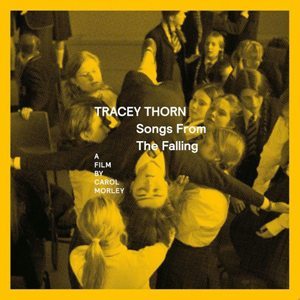

Strange Feeling, together with Buzzin’ Fly, both went on extended hiatus in 2013 to make way for my recent creative burst. They are both largely dormant now, though we still issue Tracey’s occasional releases through Strange Feeling, for example the 2014 film soundtrack she wrote for Carol Morley’s movie The Falling. But lately I have set up a new imprint, Unmade Road, as a vehicle for my new solo work, and I have done a label services deal with Caroline International to help it run globally.

It’s fair to say that you pioneered internet usage in the 90s. How do you view the impact it’s had on music?

It’s fair to say that you pioneered internet usage in the 90s. How do you view the impact it’s had on music?

I remember when the World Wide Web first appeared in the early 90s. I was immediately captivated. I taught myself basic HTML and designed the first Everything But The Girl website, launched in 1993. It was such a novelty – a band with a website – that Internet Today magazine put us on the front cover. Buzzin’ Fly made great use of cheap digital marketing through websites and email databases in the early 00s, and then of course social media really took over a few years later. With all these things you have to work them to your advantage.

The downside is: they are cheap to use and this leads to market saturation. We are awash with music. Yes, production and distribution costs have come down so much that anyone can release stuff, which is a good thing, but it does bring problems. The fact that five per cent of the artists sell the vast majority of the music means a hell of a lot of other artists are picking up the small change. A lot of power is also now in the hands of the filters and mavens, by which I mean the dominant radio stations and big music websites and streaming services. They are the gatekeepers of much of what we get to hear, because if we tried to keep up ourselves there would be no hours left in the day. I have sympathy with bands starting out now on their own. Getting on the first rung of the ladder is easy, but the distance between the first and the second has never been wider.

Fever Dream is out on 8 April.