“They Tell A Larger Story”: Vikki Tobak On The Visual History Of Hip-Hop

Vikki Tobak, author of the book ‘Contact High: A Visual History Of Hip-Hop’ talks hip-hop’s forgotten legacy in photographs and her new exhibition.

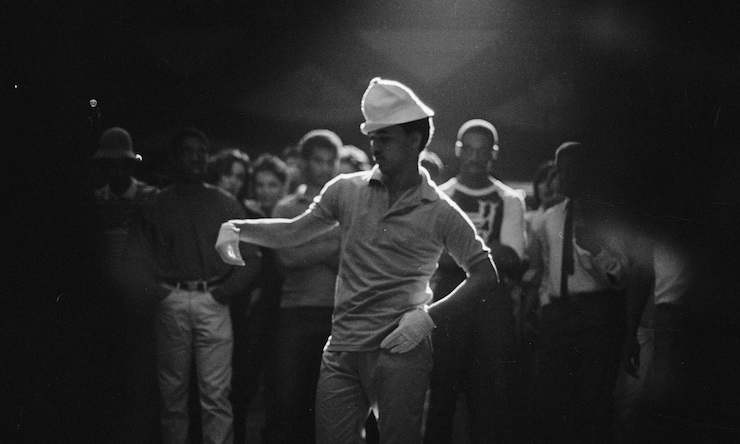

The spirit of hip-hop has always been about self-creation. When a DJ named Kool Herc extended the drum breaks on his favourite funk records using two turntables in the South Bronx, did he know he was inventing a genre of music that would eventually dominate the world? When a high-school student named Joe Conzo Jr photographed Herc and his classmates’ group, Cold Crush Brothers, did he know his work would be displayed in a museum all these years later?

Be it music, art or photography, everyone seems to be making it up as they go along. The same could be said for journalist, photographer and now curator Vikki Tobak, whose visual compendium of hip-hop history, Contact High: A Visual History Of Hip-Hop, is the subject of a new exhibit at the Annenberg Space For Photography in Los Angeles that runs from 26 April through 18 August.

“They reveal truths that a single photo cannot”

“I started thinking back on all those photo shoots that I was a part of, all those photographers I knew – where are the outtakes?” Tobak tells uDiscover Music.

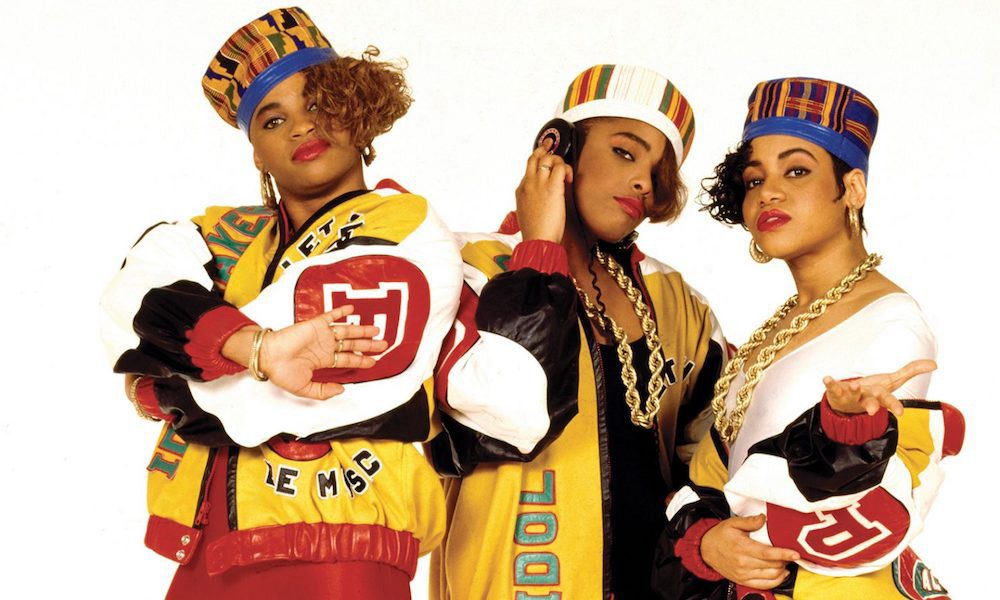

The exhibit operates as a kind of greatest hits, containing images from the book that are already burned into the collective memory of rap fans. There is Al Pereira’s 1989 black-and-white photo of Big Daddy Kane getting his flattop trimmed by dancer Scoob Lover; Janette Beckman’s bright and playful photo of Salt-N-Pepa in spandex; and Jay Z’s first photoshoot in 1995, just to name a few.

The sprawling exhibit contains nearly 140 photographs and 75 contact sheets: the work of 60 photographers that spans the last 40 years. While working as a journalist for CNN and CBS, Tobak became enamoured with photography and, specifically, contact sheets.

“They contain all of the outtakes from a photo session, which can tell a larger story and reveal truths that a single photo cannot,” says Tobak.

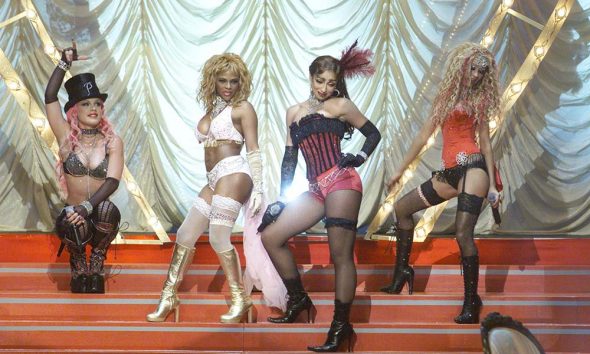

Photo: Janette Beckman, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

“They recognised hip-hop’s importance before the rest of the world”

The gears were turning for Vikki Tobak. She wanted to know more about the stories behind the shoots, so she started calling up photographers, asking them to dig in their archives and pull out all negatives, searching for the story behind these historic images.

“So many of them recognised hip-hop’s importance before the rest of the world did,” says Tobak.

Contact High was three years in the making – an insurmountable feat were it not for Tobak’s previously existing connections in the world of hip-hop.

Even before falling in love with hip-hop, Tobak’s musical roots took hold in Detroit. Born in Soviet-era Kazakhstan, Tobak and her family came to the US as refugees in the late 70s when she was five.

“I landed in Detroit – a predominantly black city, predominantly music-oriented city, where music is everywhere you go,” says Tobak. “You hear Motown, you hear Aretha and Stevie Wonder, that was my impression of what America was from the start.”

When hip-hop made its way to Detroit, it seemed like a logical progression of the music that already existed in the city. While in high school, Tobak had been going out to gay clubs like Club Heaven, Majestic and Music Institute – were epicentres of DJ-based electronic music – before moving to New York at 18 to get involved in hip-hop any way she could.

“It was underground, but starting to recognise its power”

“A friend of mine got me a job at this important club called Nell’s,” explains Tobak. “It was like a big hangout in the 80s for Warhol and Cher, but by the time I got there in the 90s, it had become an upscale hip-hop place. Russell Simmons practically lived there, and they shot [Notorious BIG’s] ‘Big Poppa’ video there… it was at this moment when hip-hop was still kind of underground but was starting to recognise its power.”

Tobak made connections and found herself covering music for Paper magazine while simultaneously holding down her Nell’s job and working at an upstart rap label by day. Payday Records, and its sister business, Empire Management, operated out of a small loft with four employees and no heat on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

“Because I was doing so much, like taking the guys to interviews, interfacing with the media and stuff, they made me the director of marketing and PR, but I was still answering phones too. We were doing everything!” says Tobak, whose fondest memories at Payday revolve around the rap duo Gang Starr, who brought artists like Jeru The Damaja and Group Home to the label.

“That’s how I met a lot of photographers who are in this book now,” explains Tobak. From the pioneering hip-hop photographer Jamil GS to award-winning Delphine Fawundu, both used to shoot press photos for Payday.

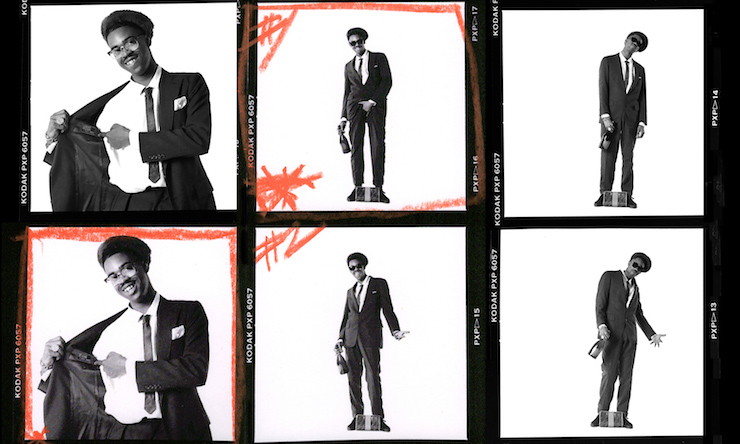

Photo: Barron Claiborne, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

“The Mona Lisa of hip-hop”

One of the highlights of the exhibit comes from what Tobak refers to as the “holy grail of contact sheets”. It’s one of the most enduring images of hip-hop: Barron Claiborne’s 1997 shot of a crowned Notorious BIG, taken six weeks before the MC was murdered.

“I jokingly call that photo the Mona Lisa of hip-hop,” says Tobak. “It is a defining photo when you think of Biggie. To see that there’s that goofy, laughing guy on the contact sheet, it was so cool to see that. People have a surprised reaction when they see it, but also those who knew him were like, ‘Oh, that’s the Biggie that I know.’”

Tobak also conducted extensive interviews for most of the photographers featured in Contact High, including Clairborne, the man behind the iconic image.

“Barron said the reason he photographed Biggie with the crown is that he was seeing all these photographers taking pictures that weren’t doing justice to young, black men,” says Tobak. “He told me, ‘I was a young, black man at the time, and I was given the power to take a photograph of someone just like me – my age, my background, my everything. I really wanted to make that statement of photographing him like royalty.’”

The Contact High exhibit not only features photography but rare ephemera from the era, from the very crown that adorned Biggie’s head to Rakim Allah’s personalised jacket that the rapper wore in the 1988 Drew Carolan photos for the second Eric B & Rakim album, Follow The Leader.

“I wish I had used another photo”

It seems Tobak has been able to procure just about every iconic image of an MC or DJ from every era. The scope and breadth of what she has accomplished is almost overwhelming, but was there a photo she wasn’t able to include?

“The second to last shoot in the book was supposed to be a portrait of Nipsey [Hussle] by Jorge Peniche, who is a great photographer and Nipsey’s road manager who’d been photographing him for years,” Tobak says.

The photo in question was of the late rapper and his daughter on his lap, pretending to drive a car. Hussle preferred not to include his daughter in published photos and Tobak honoured the request.

“I wish I had used another photo or checked back with him,” says Tobak. “Especially when it’s become so apparent what he meant to the community and to hip-hop.”

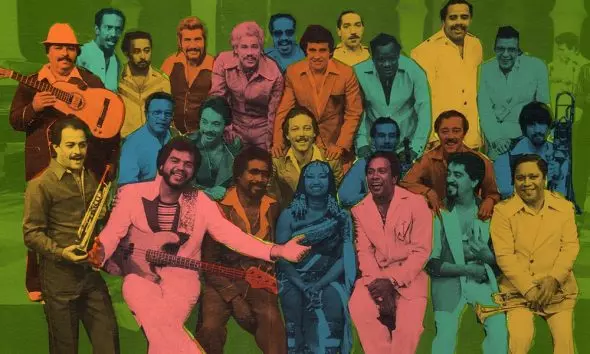

Photo: Joe Conzo Jr, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

A Great Day In Hip-Hop

Gracing the front wall of the Annenberg is a massive reproduction of A Great Day In Hip-Hop, Gordon Parks’ 1998 photo of an astounding 177 rap luminaries, a direct homage to Art Kane’s 1958 photo A Great Day In Harlem, which captured 57 renowned jazz musicians on the same steps.

If being able to identify as many people as possible in the photo is a barometer of rap knowledge, Tobak estimates that she is in the 95th percentile – an impressive measurement by any standard.

Who are the stars of Contact High? Is it recording artists like Slick Rick, Nas, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Eazy-E and Kool Keith, whose images are contained within the photographs? Photographers such as Danny Clinch, Sue Kwon and Trevor Traynor, who captured them?

Or maybe the star is Vikki Tobak herself, for having the vision to see the inherent value in all those contact sheets that had been collecting dust in drawers and storage lockers for years.

Contact High: A Visual History Of Hip-Hop is on display at the Annenberg Space For Photography from 26 April through August 18. Visit the museum’s official site for more details.