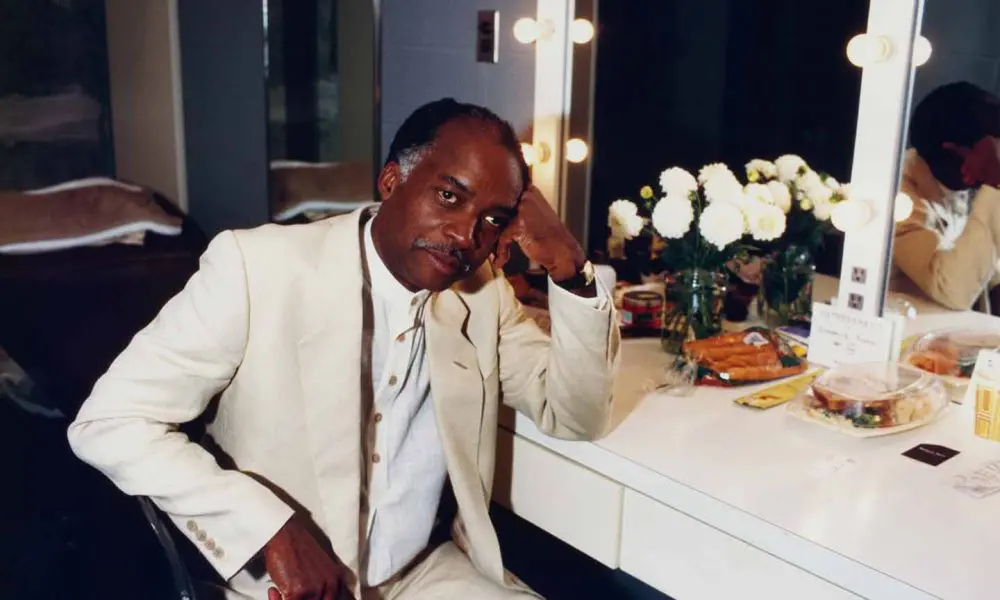

Ahmad Jamal, Jazz Giant, Dies At 92

The Pittsburgh-born jazz pianist known for introducing the world to a softer side of bebop has passed away.

Ahmad Jamal, the Pittsburgh-born jazz pianist known for introducing the world to a softer side of bebop, has passed away at the age of 92.

He died on Sunday (April 16) at his home in Ashley Falls, Massachusetts, after succumbing to prostate cancer, his daughter, Sumayah Jamal, confirmed to The New York Times.

Renowned for his supremely delicate touch, Jamal developed a distinctive playing style that combined sparkling melodies with dreamy, gossamer chords. Compared to flamboyantly virtuosic modern jazz contemporaries like Erroll Garner and Oscar Peterson, he preferred a more understated approach, building drama by inserting pauses between his melodic phrases and through contrasts in volume and coloration. It was a style that had a profound influence on the work of jazz trumpeter and friend Miles Davis. “He knocked me out with his concept of space, his lightness of touch, and the way he phrased notes and chords and passages,” Davis wrote in his 1988 memoir Miles: The Autobiography.

Although he released nearly 70 albums during his seven-decade career, Jamal is best remembered for one LP in particular: At The Pershing: But Not For Me, a live album full of lush ballads and lightly swinging grooves he recorded with his trio in 1958. An instant cocktail party classic with serious jazz intent, it would end up selling over a million copies and spending 107 weeks in the U.S. pop album charts. “Life changed and it’s constantly changing as a result,” he told uDiscover Music in 2019, speaking to the album’s impact. “It’s been the thing that has paid the bills for the last 61 years. And it still lives on. It’s really amazing.”

In the 1970s, when the popularity of straight-ahead jazz began to decline, the pianist embarked on a jazz-funk phase, playing with electric keyboards and expanding his repertoire to include covers of contemporary soul and R&B hits. He returned to his beloved Steinway grand piano in the 1980s, but no matter what he was playing on, his music never lost its sense of wide-eyed beauty and refinement. “Performing is like being the matador in the bullring,” he told The Boston Globe in 1988. “You have to be constantly concerned about what you’re doing or you get gored.”

Jamal was an urbane, articulate man who was known to be a bit guarded with the media. Though he laughed a lot during interviews, he was highly sensitive to any probing of his personal beliefs and rarely talked about his Islamic faith, which he started practicing in 1950. In 1986, he famously sued jazz critic Leonard Feather after Feather referred to him by his birth name in an article; following the incident, he would consent to do interviews if journalists agreed to adhere to a list of strict guidelines, which forbade any mention of Jamal’s birth name, his religion, and even Feather himself. Jamal was also open about his distaste for the word “jazz,” feeling it lacked respect for the music he made; following the lead of fellow pianists Duke Ellington and Dr. Billy Taylor, he preferred the descriptor “American Classical Music.” “The term ‘jazz’ is certainly not sufficient; it was used to try and downgrade the music,” he told the periodical American Visions in 1994.

Jamal was born on July 2, 1930, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to parents Robert Jones, a steelworker, and Lottie, a house-cleaner. He started showing interest in his family’s upright piano when he was a toddler. “One day when I was three years old, my Uncle Lawrence was playing it and he began to tease me and said ‘bet you can’t play this,’” he told Record Collector in 2019. “I played every note he played, and of course, the whole house fainted as that was the first time I ever sat down at the piano.”

Recognizing his unusual talent, his mother started saving up money for piano lessons. “[She] walked to work in order for me to have a dollar for my music lesson,” Jamal would tell jazz critic Bill King in 1990. “Her sacrifices were made every day.”

When he finally started training in European classical piano at seven, Jamal’s progress was rapid; by the time he was ten, he’d even played his first paid gig. As he continued playing semi-professionally into his teens, jazz cast a deep spell on him, and he became particularly enamored with the music of fellow Pittsburgh pianist Erroll Garner, who was ten years his senior and noted for his florid style. “He was my biggest influence,” he told Record Collector. “He went to the same elementary school and high school I went to. Our mothers knew each other.” Another inspiration was the virtuoso pianist Art Tatum, who Jamal met when he was 14. After hearing him play at a Pittsburgh jazz club, the musician, who was legally blind, hailed the youngster as a “coming great.”

By the time he began his recording career in 1951, Jamal had graduated high-school, toured with a couple of swing groups, and relocated to Chicago, which he would later describe to the Chicago Tribune as “a melting pot for a tremendous amount of talent” at the time. A year earlier, he’d converted to Islam and adopted the name of Ahmad Jamal, joining thousands of Black Americans who would gravitate to the faith in the 1950s.

During his thirteen years in the Windy City, he fronted a drummerless trio called Ahmad Jamal’s Three Strings, modeled on Nat King Cole’s piano, guitar, and bass ensemble. His first record was a stripped-back rendition of the “The Surrey With The Fringe On Top,” a song from the Rodgers & Hammerstein musical Oklahoma!. Its cool, laidback sound was the antithesis of the frenzied, hard-driving bebop his peers were making on the East Coast, but it found an early fan in an up-and-coming Harlem trumpeter named Miles Davis, who was beginning to establish himself as one of the chief architects of post-bebop modern jazz.

During the 1950s, Davis would end up covering thirteen tunes that the pianist had made his signature, including “Ahmad’s Blues,” “The Surrey With the Fringe On Top,” and most famously of all, “New Rhumba,” which appeared on his Gil Evans-arranged 1957 orchestral album Miles Ahead. “If you listen to some of [Miles’] first recordings, it had a lot to do with what he heard from Ahmad, in terms of tuning and conceptualizing the music,” Davis’ drummer at the time, the late Jimmy Cobb, told Billboard in 2019. In his memoir, Davis was effusive in his praise for Jamal. “I loved his lyricism,” he wrote. “[He] was a great piano player who never got the recognition he deserved.”

Despite Davis’ enthusiasm, the pianist had his detractors; as his profile rose in the second half of the 1950s, some jazz critics derided him as a glorified cocktail pianist, citing his tinkling piano melodies and easy-on-the-ear grooves. Others, like noted American jazz critic and author Stanley Crouch, saw him as a pioneer. “Through the use of space and changes of rhythm and tempo, Jamal invented a group sound that had all the surprise and dynamic variation of an imaginatively imagined big band,” Crouch wrote in his 2006 book, Considering Genius: Writings on Jazz.

Jamal’s so-called “chamber-jazz” aesthetic — a descriptor some critics used to describe his elegant small-group arrangements — reached its apotheosis on At The Pershing: But Not For Me, which he recorded for Chess Records’ jazz imprint Argo during a residency at the eponymous Chicago hotel in 1958. By then, Jamal had replaced his guitarist with drummer Vernel Fournier; together with bassist Israel Crosby, Fournier imbued the pianist’s music with subtle syncopations, elevating standards like the Gershwin brothers’ “But Not For Me” and Karl Suessdorf and John Blackburn’s “Moonlight in Vermont” into multi-layered musical conversations. The group seemed to play with one mind, as though guided by telepathy. “When you’re working together doing five sets night after night, you develop a cohesiveness and a musical cement that’s unequaled,” Jamal would tell uDiscover Music. “The result was beyond my wildest dreams.”

The album’s centerpiece was “Poinciana,” a languorous ballad purportedly based on a Cuban folk song that had previously been recorded by Glen Miller and Bing Crosby in the 1940s; Jamal transformed the song into an exotic tone poem, with shards of crystalline melody sparkling above softly shimmering chords and a bubbling undercurrent of percussion. “Poinciana” would become Jamal’s most famous song. Partly due to its popularity, the album became a huge success, crossing over into the U.S. pop charts for two years. Decades later, in 1995, the song would capture the popular imagination once again when it appeared in director Clint Eastwood’s The Bridges Of Madison County, which was set in the late 1950s.

At the end of 1958, Jamal cemented his success with a lightly swinging instrumental version of Doris Day’s 1954 chart-topper, “Secret Love,” which peaked at number 18 in the U.S. R&B charts. Newly flush, Jamal decided to try his hand at the restaurant business. After opening an alcohol-free restaurant in Chicago called The Alhambra and closing it a year later, he disbanded his trio, moved to New York, and took a three-year break from jazz, hoping to recharge.

When he returned to music in 1964 as the leader of a new trio, his music had become more experimental, foregrounding open-ended modal jazz-style pieces and percolating Latin rhythms. Still, he never abandoned the wistful lyricism that was his hallmark, producing music that was markedly more accessible than the more avant-garde territory his peers were exploring.

In 1969, he made a second foray into business — this time putting his solo career in the backseat to open his label and production company, Jamal, in New York. Though he assembled a promising roster of artists — including the virtuosic bebop saxophonist Sonny Stitt — the venture wasn’t a success, and he shuttered it in 1971.

Disappointed by his short spell as a record company owner, he decided to focus on his music again, signing with 20th Century Records in 1973. During his seven years with the label, he produced some of the most varied music of his career, ranging from conceptual orchestral pieces, to instrumental soul covers, to original jazz-funk material that saw him expanding his palette to include electric piano and even synthesizers. He also landed four albums in the American R&B charts — including 1974’s Jamalca, a piquant marinade of electric jazz, soul, and funk.

In the 1980s, Jamal abandoned the pop-style production values and layered arrangements that had defined his 1970s output, gravitating back to the acoustic piano and performing mostly within trio or quartet formats. Even during his twilight years, he continued releasing new music on a near-annual basis. Although he eased back on his touring schedule in 2014, he continued playing one-off gigs until his 90th birthday, in 2020. His final LP, 2019’s Ballades, which peaked at number 4 in the U.S. jazz charts, consisted mainly of solo acoustic piano pieces; it also included a striking interpretation of “Poinciana,” which he transformed into a rhapsodic keyboard improvisation, full of finely spun embellishments and surprising dynamic contrasts.

Ahmad Jamal was the recipient of several honors during his lifetime, including an NEA Jazz Masters award, in 1997; the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, in 2007; and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, in 2017. Though he was never a household name, he counted among his fans not only one of the greatest trumpet legends of all time (Davis), but also contemporary American jazz pianists like Matthew Shipp, Jason Moran, and Aaron Diehl — not to mention hip-hop legends like Nas, De La Soul, and Jay-Z, who all sampled his music in the 1990s.

Though he was a versatile musician whose recordings ranged from small group acoustic jazz to dancefloor-friendly electric funk, Jamal’s most profound legacy is that of a pianist who led a quiet jazz revolution in the 1950s. Though he wasn’t a prolific composer, his delicate, almost deconstructed arrangements of jazz standards were distinctive enough to feel like original compositions in their own right.

At a time when many of his peers were chasing down power and intensity, Jamal’s tinkling piano filigrees showed the world a more sensitive side of the art form, demonstrating that even the smallest musical gestures can make a big impact.

In 2013, a reporter for The Guardian asked him about the inspiration behind his elegant tunes: “It’s a divine gift, that’s all I can tell you,” he said. “We don’t create, we discover — and the process of discovery gives you energy.”

Deborah Hardwick

April 18, 2023 at 10:53 am

My Sincerest Condolences To The Family of The Great Maestro, Ahmad Jamal

Another Musical Genius Has Left Us

Peace and Blessings Be Upon Him!!!!

Although He Has Left Us, His Magnificent Artistry Lives On!!!!!!

Thank You.

Robert L Siefman

April 19, 2023 at 1:38 am

I had the pleasure of knowing Ahmad when he had his group with Jamil Nasser Frankl Grant and Azzedin Weston . He was playing regularly at Baker’s in Detroit where I grew up. He was a true master of music and one of the most gracious and wonderful people you could ever know. My heart goes out to his family!!!