Virgin: The Electric 80s

It was early in September 1982 when a new Virgin release was heard on the radio for the first time; from its gentle opening it morphed into a white reggae influenced song that captivated record buyers in Britain, storming to the top of the charts, and by early 1983 it was at No.2 in America. Culture Club’s ‘Do You Really Want To Hurt Me’ was not just a different sound, they were a band that looked different, they were different. Soon they were not just the biggest pop band in the world, they were also the most controversial. Culture Club followed their debut with a string of top 10 hits on both sides of the Atlantic, including a No.1 in the US with ‘Karma Chameleon’, but it was not officially released through the label as Virgin’s identity had yet to be established in America. It wouldn’t be until 1987 when Cutting Crew’s anthemic ‘(I Just) Died In Your Arms’ that Virgin Records, who had by now opened their own US office, secured the label’s first bone-fide US No.1.

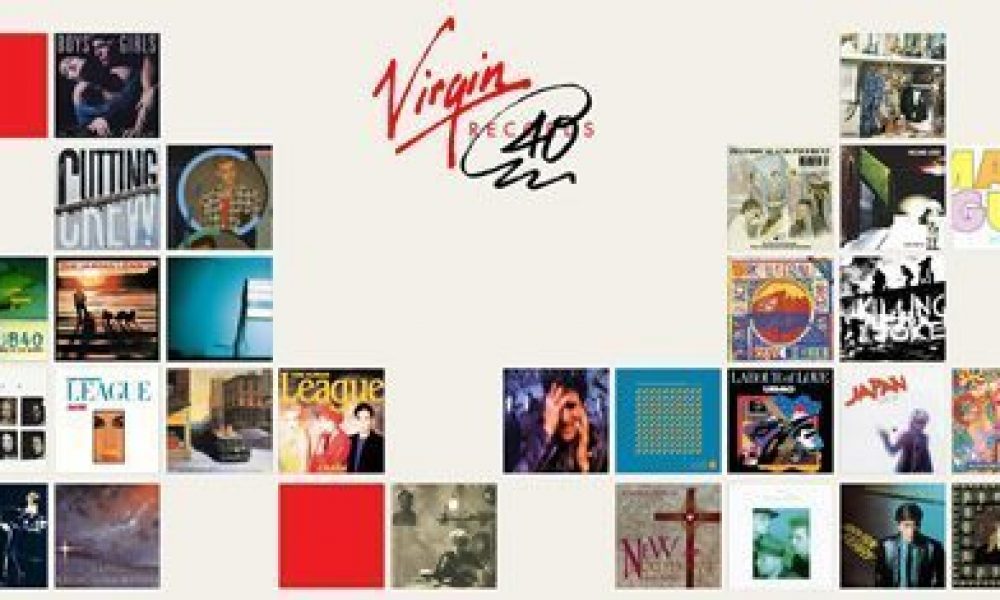

In the summer of 1984 America was introduced to another facet of Richard Branson’s business empire when Virgin Atlantic Airways began flying to New York from London. It was all part of a plan for world domination, of which the record label was an integral part. From its beginnings in the 1970s (read our Virgin 40: The Early Years feature to learn more), Virgin Records had pioneered electronic music with acts such as Tangerine Dream and they would reap the benefits of their influence through Electronica and Synth pop bands like Human League, Heaven 17 and OMD, while Japan and David Sylvian continued to show that the label was tuned into what was hip and different. Virgin also signed bands that were more rock influenced, among them Simple Minds and Cutting Crew. With Danny Wilson and UB40 they discovered bands that were polar opposites of the pop canon, but both made stylish records that proved to be very popular. By the time Virgin bought the EG label, whose stars included Roxy Music, Bryan Ferry, Eno and Killing Joke, they successfully cornered the market for the eclectic, Electric 1980s.

When in 1967 Jimi Hendrix’s voice crept out of the speakers during the song ‘Third Stone From the Sun’, promising “to you I shall put an end, you’ll never hear surf music again”, we knew what he meant. 1967 was a watershed year for rock music but then tides come in and out. Psychedelia didn’t kill surf music just as punk didn’t terminate progressive rock. But subtle changes were coming.

Virgin Records, which started out as a mail-order-only business before literally becoming the hippest vinyl store in London town (and over a shoe shop at that) was, no pun intended, instrumental in a shift towards experimental sound. By the time we reached the electronic 1980s there was every chance one could listen to an album or go to a concert where few if any traditional instruments were used. The synthesiser, which only two decades earlier had been the domain of avant-garde neo-classicists like Karlheinz Stockhausen became de rigeur kit amongst new wave rock groups. While there had been resistance to technological innovation – many fearing the machines would take over – in fact, electronic music in inquisitive young hands proved to be just as organic as any guitar, bass and drums group from previous eras.

Virgin’s initial releases in 1972 appeared on the eve of glam rock. Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells, Flying Teapot by Gong and The Faust Tapes all made partial use of rudimentary electronica but it was the signing of Tangerine Dream, during their “Virgin Years” which had the most impact on emergent Krautrock. Their early adoption of sequencers, unreliable Moog synthesiser and almost unheard of digital technology seemed so futuristic that audiences were frequently as baffled as the Luddites who booed when Bob Dylan turned folk electric. Of course what the Dream did would eventually become the norm.

Robert Moog’s creation was first publicly demonstrated at the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967 and was heard on groundbreaking ’60s cuts like The Beatles’ ‘Here Comes The Sun’, but it was Roxy Music’s Brian Eno who introduced the VCS3 synthesiser to the stage and to Top of The Pops. Making full use of the VCS3’s low-frequency oscillators, filters and eerie noise generator, Eno was fascinated by the medium and was delighted when Bryan Ferry suggested “let’s try for some lunacy, make the damn thing sound like we’re on the moon”, during sessions for ‘Ladytron’. As sax player Andy Mackay said, “we certainly didn’t invent eclecticism but we did say and prove that rock ‘n’ roll could accommodate – well, anything really.” That was Eno’s contention. During recording of the second Roxy album, For Your Pleasure, Eno began immersing himself in Krautrock and modeled his work in the track ‘The Bogus Man’ on the Köln School, and Can in particular. Eno too is responsible for the tape effects on the title track, the chilling tape loops on, ‘In Every Dream Home A Heartache’ and the crunchy VCS3 solo on ‘Editions of You’, where he actually trades ‘licks’ with Mackay’s sax and Phil Manzanera’s treated guitar.

Roxy Music were as influential on the electronic ’80s as any band bar Kraftwerk but in fact when people talk of their inspiration it’s likely they’re citing Eno’s flamboyant imagery and unearthly sonics. Eno didn’t want to stand still, musically speaking, and his albums from Here Come The Warm Jets, via the ambient Music For … series to the ambient styling of Before and After Science exerted a considerable evangelical hold on everyone from The Human League to Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. He was the kind of person who opens up new worlds of possibility.

The idea that popular music was capable of innovation in the years after Elvis Presley is very evident in The Human League and OMD. The League’s advance publicity included an “Electronically Yours” sticker, catchphrases like “beware of sugar-coated bullets”, a computer printout of the band’s world-view, and a demonstration tape that spliced music and self-satirising commentary. They didn’t use the conventional rock line-up. Drums, bass and guitars were jettisoned in favour of two synthesizers, controlled by Ian Marsh and Martin Ware. In their view, unlike say fellow Sheffield band Cabaret Voltaire, or the agit synth combo Throbbing Gristle who used electronics to treat standard acoustic instruments, “synthesizers are best used as synthesizers.” According to Ware: “Anyone can sit around and be weird. The very early stuff we did, we wouldn’t even consider letting people listen to it now, but it would compare favourably with a lot of the output of those other bands that have been compared with us, because it was more overtly experimental.”

According to Ware, “It’s a matter of discipline. What we’re aiming for is to be professional. People are going to be more impressed if they think a lot of work has gone into something than if you shamble on stage and do something that you self-consciously think is very valid and arty, and tell them they can either take it or leave it. We’re not interested in that.”

Marsh and Ware were also not interested in Phil Oakey’s notion of the torch song and opted to quit Human League to form Heaven 17 as a far more underground, club orientated act with new singer Glenn Gregory. While Oakey perfected a kind of nonchalant, witty parochialism, Heaven 17 wanted the full Giorgio Moroder flavoured synth disco in New York kit and caboodle and they achieved that with room to spare on the magnificent Penthouse and Pavement disc.

Across the Pennines, OMD’s Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphries – the Lennon and McCartney of electronica – were coming from a slightly more traditional angle. “We’d grown interested in German music like Kraftwerk as an alternative to what was around in ’75/76, so we’d already developed our musical influences before the punk explosion,” Humphries said at the time. So, instead of going for the loud-fast guitar route, they embraced synthesizers.

After passing through several genealogically interesting but otherwise minor outfits, the grandly named Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark – a duo joined by Winston, a tape deck – hit the club circuit. “At the end of ’78, when we started to be OMD and play our songs live,” said McCluskey, “there were openings for bands like ourselves. The great thing about punk, even though we didn’t want to sound like a punk band, was that it opened loads of clubs all over the country.” Despite an unorthodox bass/keyboards/ backing tapes lineup, “There was no resistance, perhaps because it was just the two of us belting out dancy pop songs, strong melodies and strong rhythms. We weren’t standing onstage being poseurs.”

The League and OMD produced a trilogy of albums apiece that personified The Electric ’80s perfectly. Even after Ware and Marsh’s departure the now in charge singer Phil Oakey continued to utilise treatments and overt synthetic textures. The massive selling Dare, Hysteria and Crash discs coincided with the zenith of the form as they let rip on a variety of Casios, Korgs and Rolands (the Jupiter-4 and MC-8 were favoured) and spent as much time on programming with producer Martin Rushent as they did assembling the basic tracks.

For OMD the ideal combination of pop formatting and exploratory digital technology is heard on Dazzle Ships, Junk Culture and Crush. They too now demanded everything from the emulator to the Prophet 5 but the predominant effects come from the Roland JP8 and the Fairlight CM1, which bathed the songs in sufficient warmth to negate any charges that this music was de-humanising. Quite the opposite.

The argument between those who craved so called organic rock against those who embraced the sampled future meant that even apparently conventional groups were delighted to involve new tech. Simple Minds not only littered their album New Gold Dream with effects, they went so far as enlisting the undisputed master of computer keyboards Herbie Hancock, whose solo on Hunter and the Hunted is a highlight. Describing the mega selling Sparkle In The Rain as “an art record but one without tears and masses of muscle”, singer Jim Kerr neatly summarized the belief that electronic sound and stadium rock ambition could cohabit. The Minds’ Michael MacNeil had been mightily impressed by Hancock of course and his own synth playing capabilities increased exponentially, as can be heard on the re-mastered Once Upon a Time CD.

Of all the artists operating within the electronic genre for Virgin Japan are probably the most single minded – certainly David Sylvian is. The influences of jazz, ambient, avant-garde and progressive rock are everywhere in his canon. The notion that he was a new romantic glam rock figure may have been accurate for a while but has been eroded over time by the sheer audacity of his output.

The Electric ’80s were a golden era for Sylvian. He worked with Ryuichi Sakamoto from Yellow Magic Orchestra, the experimental trumpeter Jon Hassell, Can’s Holger Czukay, Michael Karoli and Jaki Liebezeit. One may also find a link to Eno in Sylvian’s growing interest in multi-media installations and ambient pieces like ‘Steel Cathedrals’. Tapes, treated pianos and the full range of synths on albums like Gone to Earth, Secrets of the Beehive and Plight & Premonitionare evidence of the artist using the studio as an overarching instrument in itself – in much the same way that The Beatles and George Martin exploited EMI Abbey Road and Trident in Soho.

Killing Joke might not strike many as a band concerned with the minutiae of electronica, but of course leader Jaz Coleman is an accomplished keyboards player and he insisted that the heavily mixed and programmed Brighter Than a Thousand Suns be recorded in Hansa’s Tonstudio in Berlin, while several other Joke discs were overseen by Konrad ‘Conny’ Plank, the console brains behind Kraftwerk, Neu!, Cluster, Ash Ra Temple and Holger Czukay of Can – the very type of acts in fact that Virgin championed in their earliest days. So it went around, Plank had influenced Brian Eno who would in turn inspire Devo and Eurythmics. Weird or mainstream, you could have both.

Culture Club, who at one point in The Electric ’80s were responsible for 40% of Virgin’s profits, characterized this melting pot of sonic change – radical at the margins, purely pop at the centre. Their Kissing To Be Clever debut, the Platinum-selling smash that is anchored by ‘Do You Really Want To Hurt Me’, ‘I’ll Tumble 4 Ya’ and ‘Time (Clock of the Heart)’ was underscored by drum programming and collaborator Phil Pickett’s keyboard synths, allowing the Club to appeal to singles buyers and dance aficionados. The album produced three US top-ten singles, a feat rarely achieved by any band. Michael Jackson’s Thriller only kept their follow-up album, Colour By Numbers, from the top spot in the US, but nothing could stop it from topping the UK album chart. Culture Club’s first seven singles went top 5 in the UK and, like Simple Minds, they were passionate about the 12″ mix because that’s when they ran riot with the new noise.

Even Culture Club were somewhat eclipsed in Virgin history terms by Nick Van Eede’s Cutting Crew, whose ‘(I Just) Died in Your Arms’ hit the top slot in America in 1987. The attendant album, Broadcast, was the first release on Virgin’s new American imprint Virgin Records America. The times were changing again. The emulator buttressed single refuses to lie down. Everyone from Eminem to Britney Spears and Jay Z has sampled it.

Birmingham’s UB40, one of the biggest bands of the ’80s, aren’t generally associated with going through the door marked “Way Out”. Surely, the accepted wisdom is that UB40 stuck to a magical pop and reggae template in producing their albums and singles, every one a precious metal of some hue or other. But no. When they made their immediately successful Signing Off debut in 1980 they lashed analogue synths onto dub beats and didn’t see why they shouldn’t. Like Cutting Crew they also topped the Billboard charts when Red Red Wine spent a week at No.1 in America in late 1988.

In 1987 the Scottish sophisti-pop trio Danny Wilson led by the brothers Gary and Kit Clark were using wildcard elements from the electronic palette such as the enigmatic “found” percussion on their ‘Mary’s Prayer’ hit. They proved with their albums that pop did not have to be disposable and later when Gary Clark went solo he continued to mine a rich seam.

In so many ways Danny Wilson epitomized what Virgin had become as a record label. Always at the cutting edge since being formed, Virgin Records took risks and signed bands that both reflected the mood of the moment, as well as showing the way that music was careering off in so many different directions during the ever-changing 1980s. As CDs replaced long-playing vinyl records, so artists looked to create a new musical order, Virgin gave them the creative space to make some of the greatest music of the decade.

For all things Virgin 40 please visit www.virgin40.com…