The Medium Is The Message – But Music Is Everything

When U2 released their Songs Of Innocence album in 2014, it was instantly available to some half a billion people, right there on their phones, their lap-tops, their desk tops, and their tablets when they woke up in the morning. Unlike in previous years, when the world’s biggest artists put out their latest LP, there was no need to hotfoot it to the record shop: everyone who had a device connected to iTunes simply woke up owning the album already. This was a defining moment, a real seed change in how we consume music. For the first time ever, people would be opting out, rather than opting in.

Today, we have grown used to having music with us wherever we go. Many of us have collections of records, CDs, cassettes, digital files and a host of other, shorter-lived formats. But how have these affected the way we listen to music? And how has each innovation in technology changed the music we hear?

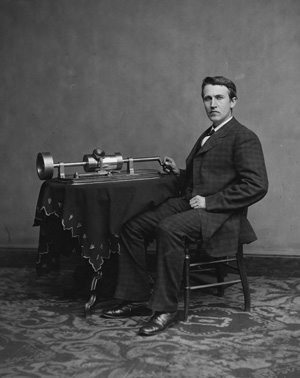

Until very recently in human history, music was hard to come by. Before Thomas Edison unveiled his phonograph, if people wanted to listen to music they had two choices: they could go somewhere where musicians were playing music; or they could play it themselves. The idea of owning or consuming music simply didn’t exist.

Until very recently in human history, music was hard to come by. Before Thomas Edison unveiled his phonograph, if people wanted to listen to music they had two choices: they could go somewhere where musicians were playing music; or they could play it themselves. The idea of owning or consuming music simply didn’t exist.

And then one day in 1877, everything changed. The young American inventor Thomas Edison shouted “Mary had a little lamb” into the horn of his latest invention: the phonograph. The machine recorded the sound waves of his voice onto a sheet of wax paper. When Edison applied a stylus to the sheet, it reproduced those same sound waves, amplified through a cone. “I was never so taken aback in my life,” he later commented. Edison’s invention recorded sound onto a sheet placed around a cylinder, rather than storing it on a disc. However, it wasn’t long before discs were more popular than cylinders – the first defunct format had been consigned to the scrap heap. The next few years saw many advances in technology, such as Emile Berliner’s Gramophone, in 1887. By the end of the century, a record player had been invented that operated when a coin was inserted. This proto-jukebox was one of a number of machines that could be found in the phonograph parlours that were springing up across the United States, and soon spread around the globe.

The earliest commercially produced Gramophone records appeared in 1901, the same year that the latest version of Berliner’s Gramophone was issued and marketed by the Victor Talking Machine Company. Victor’s recorded music division released a disc by the Italian tenor Enrico Caruso, whose popularity would make him the first star of the record industry.

The earliest commercially produced Gramophone records appeared in 1901, the same year that the latest version of Berliner’s Gramophone was issued and marketed by the Victor Talking Machine Company. Victor’s recorded music division released a disc by the Italian tenor Enrico Caruso, whose popularity would make him the first star of the record industry.

Over the next few decades, improvements to mass production were the most important concern to the record business pioneers. Caruso’s recordings were issued on 78rpm 10” discs. While cylinders may have offered certain advantages over discs, it was becoming increasingly imperative that methods for mass-producing records were found, as musicians and singers were having to record and re-record their songs over and over to keep up with demand, sometimes singing the same song hundreds of times in a day.

One thing that Edison realised fairly early on was that recording music wasn’t simply a case of providing a representation of the music, but that recorded music itself would become a new instrument – a belief born out in sampling, synthesisers, looping and all kinds of sonic experimentation that we now take for granted. Records weren’t just about recording the performance, they could themselves become the performance.

One thing that Edison realised fairly early on was that recording music wasn’t simply a case of providing a representation of the music, but that recorded music itself would become a new instrument – a belief born out in sampling, synthesisers, looping and all kinds of sonic experimentation that we now take for granted. Records weren’t just about recording the performance, they could themselves become the performance.

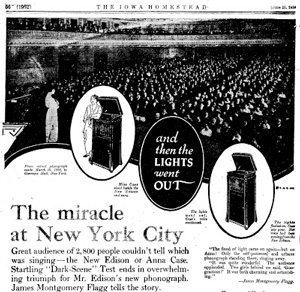

And, for a while, records were exactly that. People would turn out in their thousands to sit in a theatre, where a record player sat on the stage and played them a symphony or a song. Edison took this one step further in 1915. To demonstrate his Diamond Disc phonograph, he presented a “tone test”, whereby he played an aria from Mendelssohn’s ”Elijah, sung by Christine Miller, while the contralto sang along with herself on record. On cue, the live Miller would stop singing, leaving just her recorded voice, demonstrating to the audience quite how accurate a reproduction was now being achieved (the audience is reported to have emitted audible gasps at the effect). Such events continued to attract huge audiences for years – the most famous tone test taking place in 1920 at New York’s prestigious Carnegie Hall.

The 78rpm 10” would become the most popular format for the first half of the 20th Century. These discs could hold around three minutes of music per side, thereby dictating the length of the majority of popular songs that would remain the ideal well after the technology advanced beyond such limitations. Classical or spoken-word releases were  more likely to feature on 12” 78s, including an edited version of George Gershwin’s ‘Rhapsody In Blue’, which Victor released split over two sides of a 12” disc. Another way around the limitations of the disc length was to collect a number of records together in one package, which became known as a record album. An example of this is HMV’s 1917 recording of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado.

more likely to feature on 12” 78s, including an edited version of George Gershwin’s ‘Rhapsody In Blue’, which Victor released split over two sides of a 12” disc. Another way around the limitations of the disc length was to collect a number of records together in one package, which became known as a record album. An example of this is HMV’s 1917 recording of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado.

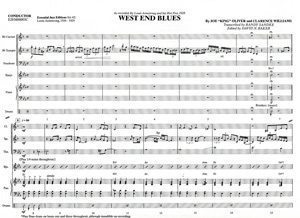

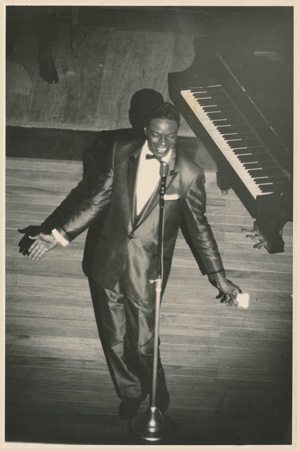

The 1920s saw a huge rise in the popularity of jazz recordings, with musicians becoming international stars. Chief among these was Louis Armstrong, who scored hits including ‘Potato Head Blues’ and the hugely influential ‘West End Blues’. These short jazzy recordings would be a hugely significant milestone in the creation of what became popular (or “pop”) music. The Charleston was the dance du jour, while orchestras such as the one led by Duke Ellington were big business. While the 20s began with Chicago as its centre, drawing acts like Jelly Roll Morton to the city, by the end of the decade, New York was becoming the hub. Broadway songs by songwriters the likes of Irving Berlin and Cole Porter began to supplement jazz standards like Fats Waller’s ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’’ as the genre’s popularity grew.

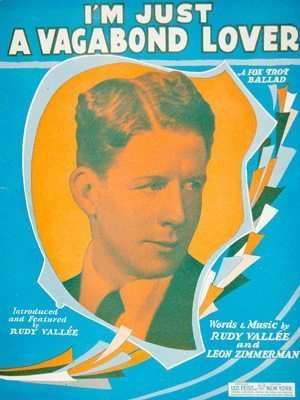

The advent of electrical recording through a microphone afforded a more gentle, romantic style of singing, once the need to be heard over a band had been removed. Jazz big bands would often be fronted by singers with a more personal style, known as crooners. Rudy Vallée was comfortably the most popular of these new vocalists. The handsome, well-tailored American singer who scored hits like ‘I’m Just A Vagabond Lover’ and ‘Deep Night’ found himself mobbed by flapper girls outside his sold-out concerts every night. Teen magazines published his picture and girls wrote letters of undying love. Vallée was the first pop idol, and his legacy remains today.

The advent of electrical recording through a microphone afforded a more gentle, romantic style of singing, once the need to be heard over a band had been removed. Jazz big bands would often be fronted by singers with a more personal style, known as crooners. Rudy Vallée was comfortably the most popular of these new vocalists. The handsome, well-tailored American singer who scored hits like ‘I’m Just A Vagabond Lover’ and ‘Deep Night’ found himself mobbed by flapper girls outside his sold-out concerts every night. Teen magazines published his picture and girls wrote letters of undying love. Vallée was the first pop idol, and his legacy remains today.

Vallée was soon followed by other good-looking gentlemen singers attracting the ardour of young women and the ire of their male counterparts: men the likes of Bing Crosby, and Frank Sinatra. A few decades after its invention, recorded sound had created the environment for the pop star, and teenagers for the next few decades would be spoilt by a seemingly endless stream of good-looking, wholesome men who would steal their hearts and become an obsession.

Vallée was soon followed by other good-looking gentlemen singers attracting the ardour of young women and the ire of their male counterparts: men the likes of Bing Crosby, and Frank Sinatra. A few decades after its invention, recorded sound had created the environment for the pop star, and teenagers for the next few decades would be spoilt by a seemingly endless stream of good-looking, wholesome men who would steal their hearts and become an obsession.

Despite the depression of the 1920s and 30s, and the post-war recession, the record business flourished. Jukeboxes had become a familiar sight throughout American cities, and soon expanded their business abroad. Billboard, the entertainment industry trade paper, began to publish its first regular charts, with its first record chart issued on 20 July 1940 (it had previously published various lists of best-selling sheet music and vaudeville songs). Billboard originally posted separate charts for jukebox selections, disc jockey plays, sales, and so on, with records divided up by genre. Among their charts was The Rce records Chart, which later became the R&B Chart. It had its origins in the blues records that were recorded in the 1920s and 1930s, often on field recording trips, where record labels sent producers and engineers through the South to capture itinerant musicians. Robert Johnson was first recorded in San Antonio in exactly this way, as were Blind Willie McTell, Big Bill Bronzy and a host of names that would later inspire young white musicians. These 78 records became the ‘music of mystical gods’ as collected by musicologist Harry Smith and circulated in the years following World War 2 on newer, more convenient, format.

Other charts also existed, such as the Harlem Hit Parade, which was topped for 10 weeks in 1943 by Nat King Cole’s ‘Straighten Up And Fly Right’. The gentle-voiced jazz pianist was signed to the new Capitol Records, with his phenomenal record sales allegedly building the company’s famous Capitol Records Tower in Hollywood, dubbed “the house that Nat built”.

Other charts also existed, such as the Harlem Hit Parade, which was topped for 10 weeks in 1943 by Nat King Cole’s ‘Straighten Up And Fly Right’. The gentle-voiced jazz pianist was signed to the new Capitol Records, with his phenomenal record sales allegedly building the company’s famous Capitol Records Tower in Hollywood, dubbed “the house that Nat built”.

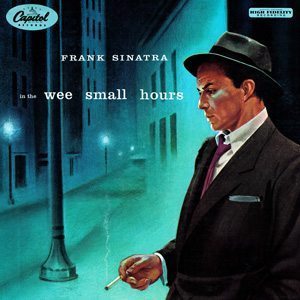

But of all of the emerging crooning stars whose records sailed up the charts at this time, Frank Sinatra had perhaps the most unique talent. Having worked – often for free – to raise his profile in New York and New Jersey, he recorded a few records with bandleader Harry James (including ‘My Buddy’ and ‘All Or Nothing At All’). Sinatra soon joined Tommy Dorsey, whose band was one of the biggest in the country. A number of successful records followed, notably ‘I’ll Be Seeing You’, which was recorded in February 1940 but became a more poignant fixture in his repertoire once the US joined World War II. As the 40s continued, Sinatra played to packed houses of screaming girls, while the hits flowed.

In the years immediately after the war, the United States’ two recording giants, Columbia Records and its more successful rival, RCA Victor, logged heads in what became known as the Battle Of The Speeds. RCA had dallied with a new, long-playing record in the 30s, but had fluffed its launch and, by the late 40s, was concentrating its efforts firmly on its high-fidelity, 7”, 45rpm disc. Columbia, with help from a former RCA Victor employee, developed its own 12” disc, which rotated at 33 1/3 rpm and which it dubbed the LP, or long-player. A 10” version was also introduced, with The Voice Of Frank Sinatra as one of its initial releases. The battle played out over a number of years, the result somewhat perversely being that the better-quality 45 became the format of choice for the shorter, pop material, while the LP was adopted by fans of classical music, usually sticklers for superior quality, but preferring the longer play offered by Columbia’s innovation.

![Big-Maceo---If-You-Ever-Change-Your-Ways-[01-cropped]](https://www.udiscovermusic.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Big-Maceo-If-You-Ever-Change-Your-Ways-01-cropped.jpg) Soon, every record label was producing discs of either style to suit its various markets. Initially, RCA even went so far as to colour code its records – popular music was black, classical was red, country green and perversely the blues and R&B were orange. Among the first releases on its orange R&B series was ‘If You Ever Change Your Ways’ by Tampa Red and Big Maceo, as well as a single by Delta blues singer Arthur Crudup, called ‘That’s All Right’, a record that would cause a storm just a few short years later when covered by a truck driver from Tupelo, Mississippi, named Elvis Presley.

Soon, every record label was producing discs of either style to suit its various markets. Initially, RCA even went so far as to colour code its records – popular music was black, classical was red, country green and perversely the blues and R&B were orange. Among the first releases on its orange R&B series was ‘If You Ever Change Your Ways’ by Tampa Red and Big Maceo, as well as a single by Delta blues singer Arthur Crudup, called ‘That’s All Right’, a record that would cause a storm just a few short years later when covered by a truck driver from Tupelo, Mississippi, named Elvis Presley.

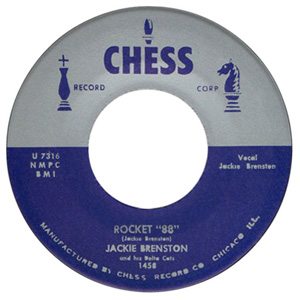

Across America, record labels sprang up in almost every town. Some were nothing but flashes in the pan, but others became legendary – particularly with what was then termed “race music”. Labels such as Specialty in Los Angeles, Chess in Chicago and Atlantic in New York produced some of the most enduring and influential records of the 20th Century.

In the jazz field along came Blue Note Records and the verve label who produced 10″ albums featuring such luminaries as Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis and Oscar Peterson. However, the major labels were transitioning from 10″ LPs to 12″ records, which gave the smaller independent labels a headache. Their cashflow was always challenging and their pockets not as deep as the major labels and so switching to the larger format was both challenging and expensive. Some smaller record labels failed to rise to the challenge. Throughout this period these jazz labels, to many in the modern world’s surprise, issued 45s of artists more normally associated with extended solos and LPs. The fact is they needed to release 45s to get their records played on the radio, and just as importantly to get them placed on the hundreds of thousands of jukeboxes across America.

By now, music was being recorded using magnetic tape, and innovators like guitarist Les Paul began to experiment with overdubbing, tape echo and multi-tracked recording. Each studio had its own sound, which was part of what made them successful. Few studios could boast a sound to rival that of Sam Phillips’ Memphis record label, Sun Records. It was here in 1950 that Ike Turner recorded the milestone single ‘Rocket 88’, credited to vocalist Jackie Brenston – a single often cited as the first rock’n’roll record. The story goes that Turner’s amplifier was damaged en route to the studio, creating a distorted guitar sound which the musicians and engineers liked so much that they not only left it on the record, but made it a feature of the song. ‘Rocket 88’ was a smash, reaching the top of Billboard’s R&B chart and launching a hundred imitators. Phillips would go on to discover and record Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins and Roy Orbison.

By now, music was being recorded using magnetic tape, and innovators like guitarist Les Paul began to experiment with overdubbing, tape echo and multi-tracked recording. Each studio had its own sound, which was part of what made them successful. Few studios could boast a sound to rival that of Sam Phillips’ Memphis record label, Sun Records. It was here in 1950 that Ike Turner recorded the milestone single ‘Rocket 88’, credited to vocalist Jackie Brenston – a single often cited as the first rock’n’roll record. The story goes that Turner’s amplifier was damaged en route to the studio, creating a distorted guitar sound which the musicians and engineers liked so much that they not only left it on the record, but made it a feature of the song. ‘Rocket 88’ was a smash, reaching the top of Billboard’s R&B chart and launching a hundred imitators. Phillips would go on to discover and record Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins and Roy Orbison.

From the earliest days of recording through to the mid-50s, much of what happened was as much by accident as by design. People favoured one format over another for reasons of convenience, and music adapted to suit the format. But a 1955 release by Capitol changed all that. Sinatra had signed to Capitol following a slump in his career in the early 50s, but an Academy Award-winning performance in From Here To Eternity saw his stock quickly rise. His third album for the label was not, strictly speaking, the first of his so-called “concept” albums, and nor was it the first popular music release on 12” LP, but it was the first concept album released on 12” LP, and it featured a suitably moody cover to match the music; In The Wee Small Hours is today generally regarded as the first “classic album”. Perhaps as a result of the collapse of his first marriage, and his affair with Ava Gardner, the theme of the album is of heartbreak, loneliness, introspection and sadness. Everything about the record is of such a high standard as to rank as perhaps the first time that pop music was elevated to the status of art. The goalposts had irreversibly shifted.

From the earliest days of recording through to the mid-50s, much of what happened was as much by accident as by design. People favoured one format over another for reasons of convenience, and music adapted to suit the format. But a 1955 release by Capitol changed all that. Sinatra had signed to Capitol following a slump in his career in the early 50s, but an Academy Award-winning performance in From Here To Eternity saw his stock quickly rise. His third album for the label was not, strictly speaking, the first of his so-called “concept” albums, and nor was it the first popular music release on 12” LP, but it was the first concept album released on 12” LP, and it featured a suitably moody cover to match the music; In The Wee Small Hours is today generally regarded as the first “classic album”. Perhaps as a result of the collapse of his first marriage, and his affair with Ava Gardner, the theme of the album is of heartbreak, loneliness, introspection and sadness. Everything about the record is of such a high standard as to rank as perhaps the first time that pop music was elevated to the status of art. The goalposts had irreversibly shifted.

Of course, Sinatra’s LP didn’t spell the end for the 45 – far from it, in fact. The rise of rock’n’roll and R&B music secured a bright future for the 7”, with artists such as Ray Charles pushing the limits of the microgroove single by extending his What’d I Say? across both sides of the disc. Innovative record producers, including Phil Spector in the US and Joe Meek in the UK, turned their short sides into miniature symphonies, refusing to allow the time constraints of the format to rein in their imagination.

Folk music’s adoption of the LP was significant in promoting the format into the 60s. Records by the likes of Nina Simone and Pete Seeger drew great admiration, but it was the success of Bob Dylan that brought the album as a thing into the bedrooms of teenagers around the world.

The phenomenal success of vocal groups in the wake of The Beatles’ rise continued the format’s popularity, with their own double-A-sided ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’/‘Penny Lane’ considered one of the finest 7”s ever released.

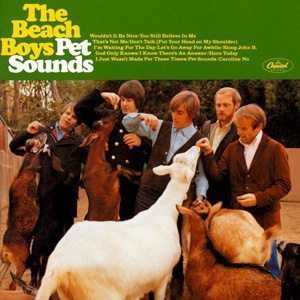

But, as young musicians on both sides of the Atlantic began taking their music more seriously, the long-playing album began to take on greater significance. The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson ceased touring with the group and dedicated himself to crafting albums as pop symphonies – 1966’s Pet Sounds remaining one of the finest albums ever produced.

But, as young musicians on both sides of the Atlantic began taking their music more seriously, the long-playing album began to take on greater significance. The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson ceased touring with the group and dedicated himself to crafting albums as pop symphonies – 1966’s Pet Sounds remaining one of the finest albums ever produced.

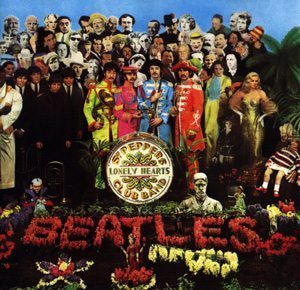

The response from The Beatles was a record that built on the format of Sinatra’s landmark LP over a decade earlier. Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band saw the Fab Four explore every possible aspect of the LP in order to make their record the best it could be. Innovations such as a pop art sleeve design by a respected artist, printing the lyrics on the artwork, using a gatefold for a pop record, a full-colour inner sleeve and even printing looping sounds on the run-out groove combined with a revolutionary sound to make the album feel like a major event.

It was the bringing together of all the various elements in a pop album that saw Sgt Pepper’s mark the moment when the LP overtook the single. From here on, while a hit single was never frowned upon, critics were primarily interested in the album to determine the artistic merit of an act. While singles still sold in their millions, they were now considered more disposable. No act demonstrated this better than Led Zeppelin. The English heavy rock group believed so strongly that their albums should remain whole listening experiences that they fought to prevent the release of singles under their name. The 70s was arguably the golden age of the LP, with acts like Pink Floyd and David Bowie exploring the limits of pop music as a work of art. Indeed, the album sleeves themselves were works of art and most people of a certain age will, if pressed, admit to buying a record simply because of its cover… In The Court of The Crimson King, anyone?

It was the bringing together of all the various elements in a pop album that saw Sgt Pepper’s mark the moment when the LP overtook the single. From here on, while a hit single was never frowned upon, critics were primarily interested in the album to determine the artistic merit of an act. While singles still sold in their millions, they were now considered more disposable. No act demonstrated this better than Led Zeppelin. The English heavy rock group believed so strongly that their albums should remain whole listening experiences that they fought to prevent the release of singles under their name. The 70s was arguably the golden age of the LP, with acts like Pink Floyd and David Bowie exploring the limits of pop music as a work of art. Indeed, the album sleeves themselves were works of art and most people of a certain age will, if pressed, admit to buying a record simply because of its cover… In The Court of The Crimson King, anyone?

With the record business now a multi-billion-dollar industry, a variety of new technologies were being developed. Tape had long been the standard format in recording studios, but now manufacturers looked for ways to use the mateiral for convenient, portable playback. The 8-track cartridge system was developed by the Lear Jet Corporation in the mid-60s to allow music to be played on flights, while the Ford Motor Company was just one of the firms to install similar systems in its cars. The advent of the compact cassette in the 70s saw a dramatic rise in home taping, while at the same time offering people the ability to have music wherever they went. The invention of the Sony Walkman, in 1970, allowed people to carry a music system in their pocket for the first time. One unintended consequence of the cassette was the rise of the mix tape…here for the first time the music became a message of a whole different variety.

As the 1980s dawned, so too did a vision of a different future. The world was turning digital, and it wasn’t long before the record business followed suit. The big bang of digital music came with the launch in Japan, in 1982, of the first commercially available compact discs (CDs). By 1985, Dire Straits had sold over a million copies of their Brothers In Arms album – the first million-selling CD. That same year, David Bowie’s entire catalogue was reissued on CD, marking the beginning of a change for listeners around the world, as they began replacing their existing collection in digital format, many people discarding records and tapes for good.

As the 1980s dawned, so too did a vision of a different future. The world was turning digital, and it wasn’t long before the record business followed suit. The big bang of digital music came with the launch in Japan, in 1982, of the first commercially available compact discs (CDs). By 1985, Dire Straits had sold over a million copies of their Brothers In Arms album – the first million-selling CD. That same year, David Bowie’s entire catalogue was reissued on CD, marking the beginning of a change for listeners around the world, as they began replacing their existing collection in digital format, many people discarding records and tapes for good.

Manufacturers, rather than musicians, were now once again at the heart of innovation, and the major companies were spending fortunes on developing new formats. Sony’s MiniDisc, launched in 1992, and promoted by Reef with their single ‘Naked’, was a small and practical high-fidelity system, but struggled to compete commercially as CD-Rs dropped in price, allowing customers to burn a CD cheaper than they could copy to MiniDisc. But it was the emergence of MP3 players that finally began to signal the end for many of these formats. Illegal file-sharing sites such as Napster saw a huge surge in music piracy, and physical sales plummeted. However, a recovery is on…

![Reef---Replenish-MiniDisc-[needs-some-cropping]](https://www.udiscovermusic.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Reef-Replenish-MiniDisc-needs-some-cropping.jpg) Today, the record business has rallied and legitimised music downloads. At the same time, the growing popularity of vinyl LPs over the past decade has seen a new generation turn to the format, with artists such as the American singer-songwriter Bonnie “Prince” Billy, French dance act Daft Punk and indie-rockers Arctic Monkeys contributing to the resurgence in the format. Today’s buyer can choose whichever format suits their own lifestyle and convenience.

Today, the record business has rallied and legitimised music downloads. At the same time, the growing popularity of vinyl LPs over the past decade has seen a new generation turn to the format, with artists such as the American singer-songwriter Bonnie “Prince” Billy, French dance act Daft Punk and indie-rockers Arctic Monkeys contributing to the resurgence in the format. Today’s buyer can choose whichever format suits their own lifestyle and convenience.

The 2015 release of Adele’s 25 saw almost a million copies sold in the UK on its first week of release, while sales in the US broke three million in just that first week, with sales split across download, CD and vinyl. And then on Christmas Eve The Beatles catalogue was made available on streaming services. It begs the question, what next?

Art Noxon

November 20, 2020 at 6:40 am

Michael Jackson, once in a lifetime musical genius.