No Static At All

In a world long ago, and seemingly far away, teenagers, packed off to bed at an unreasonably early hour, went beneath the bed covers to listen to crackling radio broadcasts – there seemed to be more static than music. This was the heyday of powerful AM radio stations where men with strange names like Wolfman Jack broadcast to teenage America, while in Britain and Europe teens listened to Radio Luxembourg, at least they did in the evening, because during the day everyone was stuck with government-owned radio stations that seemed to think that pop music was, at best, harming the moral fibre of their nation’s youth. At its worst…it hardly bore thinking about.

In early 1960s America FM radio was becoming more widely available, but initially, it was used to simulcast AM broadcasts and orchestral concerts. In 1964 pirate radio stations began broadcasting from ships in the North Sea to Britain and Europe. They too aped the kind of music that was being played on national broadcasters, only there was a lot more music, all of it pop, and there was a sense of excitement that at last music for a younger audience was available 24/7.

“Growing up in LA, white kids weren’t listening to white radio, we were listening to KGFJ, an AM station. During the day it was a 1000-watt radio station for the black community. We kind of caught it after school and as it got dark it went down to 250 watts, kind of like the way you’d have to strain to listen to Radio Luxembourg in England.” Bruce Johnston, The Beach Boys

Soon enough FM radio and pirate radio began experimenting with different kinds of music; there were shows dedicated to playing rock music (rock back then was defined as anything that wasn’t pop). In 1967 the British government banned pirate radio and took many of the DJs to work on its own Radio 1 channel, which was designed to be (slightly) more teenage friendly. In America, whole stations began broadcasting Album Orientated Rock – AOR. The revolution was in full swing.

This was when pop properly became rock; it was like when colour television came along…only way better.

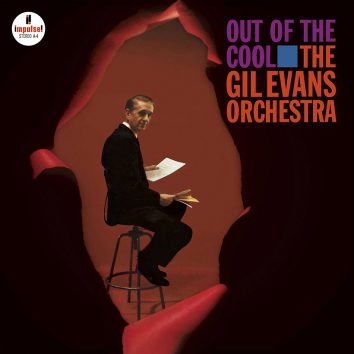

Even before AOR, FM stations were experimenting with what some called Free Form radio, before calling it Progressive (which had nothing to do with Prog Rock). Tom Donahue a san Francisco DJ is thought of as the father of free-form radio having been given a slot on KMPX-FM in San Francisco, a struggling station offering its listeners a typically bland output of Top 40 pop. Donahue had a plan and from 8pm until midnight he played his unique mix of rock, folk, some Indian ragas, even pop and soul music that fitted the overall vibe of the show.

“Top 40 radio, as we know it today and have known it for the last ten years, is dead and its rotting corpse is stinking up the airways.” Tom Donahue, Rolling Stone magazine November 1967

During the summer of love Donahue played everyone from The Beatles and the Stones to Jefferson Airplane, The Who, The Spencer Davis Group and Muddy Waters. Donahue would often play three or four songs back to back without interruption, a complete no-no on AM radio where there was as much talk as music…or so it seemed.

By early 1968 Donahue was falling out of love with the owners of KMPX, they fired him and by May other DJs on the station eventually quit and they all decamped to another San Francisco station, KSAN (94.9 FM); here they set about transforming the station into the legendary ‘Jive 95.’ During Donahue’s dispute with KMPX The Rolling Stones, The Grateful Dead and other hip bands insisted that the station not play their records.

Shortly after Donahue and Co moved over to KSAN one of San Francisco’s favourite bands, Creedence Clearwater Revival released their debut album. With their ability to be able to play credible pop that crossed the line into rock it made them an FM favourite, especially as they stretched their formula to play long cover versions of tracks like ‘Suzie Q’ on their debut or Marvin Gaye’s ‘I Heard It Through The Grapevine’ on 1970’s Cosmo’s Factory. This was meat and drink to FM radio.

With Bill Graham’s Fillmore West in San Francisco and the Fillmore East in New York becoming the de facto home of live rock on the west and east coast of America radio stations playing free form to AOR across America increased rapidly. The Allman Brothers Band, Grand Funk Railroad and The James Gang, who had Joe Walsh as their principal songwriter and guitarist were just some of the bands that became staples on Rock radio. Woodstock in August 1969 made stars of a number of artists, including Joe Cocker, The Who and Santana, but the fact was there were festivals all across America that summer with line-ups that now have younger fans drooling at what they missed.

Festivals in America changed following the disaster of The Rolling Stones appearance at Altamont Raceway, near San Francisco – having the Hells Angels handling security was not the Stones idea but it shows the level of naivety that was prevalent in rock at the time (to be fair Woodstock could have turned into a disaster as well… New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller came close to calling in 10,000 New York State National Guard troops at one point).

American FM radio did so much for British rock bands that were experimenting with their own form of progressive music – rock with classical overtones, music that was not as firmly based on the blues as bands like Cream and others. The Moody Blues album, Days Of Future Passed came out in December 1967 and was neatly placed to show just how different rock was to pop. ‘Nights in White Satin’ was soon a staple of late-night FM radio and throughout their long career the band has always been very popular in America; it’s something that would never have happened without FM radio.

In Britain, the pirate stations were learning from what FM stations were doing in America. John Peel worked on a Californian radio station in 1966 before returning to the UK in early 1967 – he heard the dawning of Donahue’s different style of radio. Peel joined pirate station, Radio London and his midnight until the early hours show, ‘The Perfumed Garden’ first broadcast in May 1967 replicated exactly what was happening in the U.S. Peel would play a very varied mix that on any show might include John Mayall, The Velvet Underground, Tyrannosaurus Rex, Howlin’ Wolf, Canned Heat, The Rolling Stones and some poetry. When he played the Stones, ‘We Love You’ in the summer of 1967 he added the sound effect of a slamming prison door to highlight Mick and Keith’s short stay in jail following the infamous Redlands drug bust.

The pirate radio stations were outlawed in August 1967 and the BBC set up Radio 1 to cater to the huge prate radio audience. Radio 1 first broadcast was at 7:00 am on Saturday 30 September 1967 – Tony Blackburn played The Move’s ‘Flowers In The Rain’ as the first complete song on the new station. However, for most of the day the station was a pop station, it broadcast on both AM and FM and shared some of its output with the older-orientated Radio 2 – much to the annoyance of anyone who craved rock.

John Peel was one of the few beacons of hope for those who liked records to (usually) be over three minutes long. Peel along with Pete Drummond and Tommy Vance hosted ‘Top Gear and later Peel also hosted ‘Night Ride’, a show that was a heady mix of rock, poetry and what we have come to call World Music. ‘Top Gear’ was made up of records and live sessions, the sessions were as a result of the BBC still being shackled by an antiquated law preventing them from broadcasting too many records, so as not to deprive musicians of work by playing live on air. This dated back to the era of the big bands and radio broadcasts that were almost entirely live. Ironically it has produced a treasure trove of performances from legendary rock bands and singers who recorded ‘in session’. Among the artists that appeared playing live on Top Gear were The Moody Blues, Captain Beefheart, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Pink Floyd, Cream, Supertramp and Elton John.

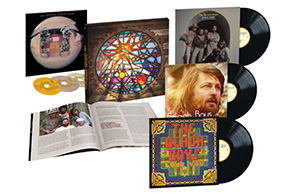

Denny Cordell who produced the Move’s ‘Flowers In the Rain’ had moved to America to live in 1968 where he set up Shelter Records with Leon Russell. It was their label that released Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs And Englishman that was recorded in concert at the Fillmore East in March 1970 and it was, along with the Allman Brothers at The Fillmore East, a seminal live rock albums that somehow transcends the restrictions of the contemporary recording equipment.

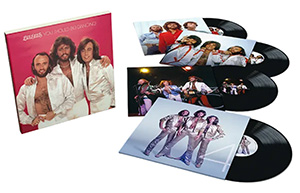

As the 1970s progressed the dominance of FM radio was such that even pop stations turned to the FM dial to deliver the music that was now better recorded than ever on multi-track equipment rather than just two or four-track machines from earlier decades. Having said that, try listening to early 1960s records in mono on small speakers and they invariably sound better. The way they are mixed and the compression that was applied to them in the final stages of production somehow make them sound so much better through a small car speaker than on hi-fi equipment.

Bands like Steely Dan seem purpose-built for FM radio with their complex and original music that needs to be heard in rich stereo detail to be fully appreciated. Truth is, they like so many others developed their music in tandem with technology. When Can’t Buy A Thrill came out in late 1972 every microgroove of the long-playing record could be heard. From the opening drum and percussion pattern of ‘Do It Again’ you are invited to sit back and be beguiled by the brilliance of Roger Nichols engineering skills in crafting a record that is totally FM friendly.

After Aja, their 6th album was released in 1976, Becker and Fagen, who were Steely Dan, were asked to write the title track for a (now) forgettable movie titled, F.M. It was a box-office flop, but the title song was a hit in many countries including the UK and America. “As long as the mood is right, No Static at all, FM”. The mood was what Donahue and just about every jock that followed them tried to achieve.

As a postscript, in 1976 Denny Cordell produced the Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers debut album and in 2002 Petty released The Last DJ, and album dedicated to the halcyon days of American (and elsewhere) radio.

And there goes the last DJ

Who plays what he wants to play

And says what he wants to say

Works for me…