Hip-Hop Heroes: The Takeover

If you were privy to Hip-Hop during the early part of the 1990s you were very definitely one of the cool kids. Back then it was music’s dirty little secret. Definitely underground, but thanks to the likes of MC Hammer, Vanilla Ice, and DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince there was a hint of it seeping through into the overground. During this time the visual elements of Hip-Hop were promoted at the forefront of the culture – cyphers, battles, graffiti art, and b-boy performances were taken from the streets and put onto TV sets all over the world.

Through the developing MTV generation shows like Yo! MTV Raps helped the culture identify itself with the masses, while mainstream movies such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Deep Cover adopted rap music and featured Hip-Hop fashion and slang as a part of their makeup. Some saw underground Hip-Hop as “pure” or “authentic”, much like punk music in the 1970s, but it began to filter through the commercial cracks becoming less niche and far more mainstream.

Going hard in the booth and creating a slice of razor-sharp musical imagery with an introduction to where they came from, artists such as the Wu-Tang Clan, Snoop Dogg, and Big L painted pictures with a reality-tinted brush that listeners could relate to on so many different levels. Hip-Hop in the 90s appeared to educate everyone intrigued with the culture and create a release for those caught up in the same struggle discussed on wax. Not always having to relate directly to subject matters, fans were able to find refuge in the delivery, instrumentation, and hardships heard on certain records. Hip-Hop opened a can of concrete honesty and emotional turmoil with gritty soundscapes that at times felt like a Martin Scorcese movie filmed in the ghetto.

“Engine, Engine, Number Nine/ On the New York transit line/ If my train goes off the track/ Pick it up! Pick it up! Pick it up!” – Black Sheep ‘The Choice Is Yours’

Closing the 80s out, the Native Tongues movement, whose founding members consisted of A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, and Jungle Brothers, hit the ground running as soon as the 90s began. While Tribe kicked things off with their debut album People’s Instinctive Travels And The Paths Of Rhythm, it was Black Sheep’s entertaining A Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing (1991) that attracted much attention due to its comical take on various subject matters whilst keeping to the same instrumental structure often followed by the rest of the Native Tongues. Introduced as one of the freshest talents in rap at the time, their debut album poked fun at the persuasive gangsta mentality (‘U Mean I’m Not’) as well as those obsessed with the Afrocentric viewpoint (‘Are You Mad?’). However, unable to keep the momentum going with Non-Fiction, their sophomore release, they’ll forever be remembered for their smash hit club anthem ‘The Choice Is Yours’, which was later cut up and used in the massively successful ‘Be Faithful’ by Fatman Scoop featuring Faith Evans.

Besides the Native Tongues movement, and the West Coast rap explosion that saw the likes of Ice Cube, Cypress Hill, and Dr. Dre pop up in headphones everywhere, the sub-genre is known as New Jack Swing had begun to find a rhythm and a home with the more commercial listener. Fusing Hip-Hop and R&B with popular dance, it was filled with programmed electronic drum loops and lyrics dominated by love, life and lust. It quickly became a new form of dance music with a Hip-Hop twist. Spearheaded by Teddy Riley [and his group Guy] and Bernard Belle, other big names included Heavy D & The Boyz and Kid ‘n Play.

Father MC, another flag-flyer for the New Jack Swing era, not only helped push the sub-genre with his own music alongside Bobby Brown, New Edition, and Blackstreet (another Teddy Riley helmed group), he helped carve out careers for two other names on the up and up. Both Mary J. Blige and Jodeci have Father MC [and P. Diddy] to thank for their fame and notoriety. While Blige appeared as a backing vocalist on Father MC’s top 20 hit ‘I’ll Do 4 U’, which sampled Cheryl Lynn’s ‘Got To Be Real’, Jodeci crooned their way through both ‘Treat Them Like They Want To Be Treated’ (look out for Diddy in the video as a backing dancer) and ‘Lisa Baby’. All three songs appear on Father MC’s 1991 debut Father’s Day.

With more of a choice musically, there were countless options available fashion-wise too in Hip-Hop. While the New Jack Swing performers preferred to be decked out in bright baggy suits with shiny shoes to give off an air of sophistication, the weapon of choice for hardcore rappers appeared to be Timberland boots, army fatigues, baggy denim, and basketball/American football jerseys. All a part of Hip-Hop culture’s freedom to express oneself and be fresh whilst doing so, the 90s did a lot of the groundwork in solidifying a stereotype garnered more towards appearances that would later be easily identifiable to anyone outside of the culture.

Moving through the boom-bap soundscapes demonstrated by Gang Starr, Nice & Smooth, and of course KRS One – his album Return Of The Boom Bap is the perfect example of what boom-bap Hip-Hop should sound like – by 1992 the underground element of Hip-Hop, which would soon be given to the masses in hardcore format by nine-man group the Wu-Tang Clan, was under the influence of the Diggin’ In The Crates crew. Aside from featuring Fat Joe and Big L, D.I.T.C. early members Diamond D and Showbiz & A.G. were soon to teach Hip-Hop fans a lesson in both authentic beat construction and lyrical excellence.

With Showbiz & A.G. releasing an EP version of their debut album Runaway Slave in March of ’92, there was much hype surrounding the New York duo before the full-length version dropped later in the year. Reintroducing “non-corniness” to the mic, not only were Showbiz & A.G. first out the gate from the D.I.T.C. camp, they were also partly responsible for the rebirth of Hip-Hop’s originating borough; the Bronx. Highly respected, and ultimately looked upon as important figureheads as far as hardcore-themed rap music was concerned, it, unfortunately, didn’t transpire into album sales. With two underrated albums to their name – the second being 1995’s Goodfellas – they will forever be an important part of rap’s rise to worldwide acclaim.

Diamond D’s career was one more tailored towards the production connoisseur. As one of the era’s go-to-guys when it came to production, it was his debut album Stunts, Blunts And Hip-Hop, under the moniker Diamond D & The Psychotic Neurotics, that solidified his place as a man any upcoming rapper should get to know; immediately.

Following his stellar verse on A Tribe Called Quest’s ‘Show Business’, the release of his first album quenched the thirst of those in dire need of more Diamond D. Full of steady rhyming and steady production, the album is still to this day regarded as an underground masterpiece. With jazz-tinged moments and slow-paced punches to the ear, in an almost EPMD-meets-Black Sheep type of manner, Diamond D gave fans a taste of what the next five years in Hip-Hop were to sound like as he, and his cut-and-scratch boom-bap sound amalgamation, promptly became the production backbone to many of the era’s upcoming projects.

“You wanna see me get cool, please, save it for the breeze/ Cause the lyrics and tracks make me funky like cottage cheese.” – Redman ‘Tonight’s Da Night’

Aside from Pete Rock & CL Smooth, The Pharcyde, and [complete with Africa medallions and tie-dye t-shirts and ponchos] Arrested Development, whose spirituality-driven 1992 debut album 3 Years, 5 Months & 2 Days In The Life Of… sold over four million copies in the US alone, Hip-Hop was continuing to be controlled by both gangsta rap and hardcore lyricism. With many eyes pointed in the direction of the west coast’s hardcore scene, two MCs on the east were soon to pull some of that attention back. With chemistry unmatched by any other collective or duo, Method Man and Redman continue to operate as rap’s ultimate Batman and Robin. Knowing what each other is thinking at any given time, it makes for one hell of a musical partnership.

Both signed to Def Jam, Jersey’s Redman began as part of EPMD’s Hit Squad while Meth’s climb to prominence came as part of Staten Island’s Wu-Tang Clan. Instantly hitting it off, their individual rhyme styles complemented one another like peanut butter does toast. Meth’s chesty tone and comical lyrical content, best previewed on 1994’s Tical and 1998’s Tical 2000: Judgement Day, when met with Red’s reggae-inspired funk delivery and fluid wordplay (see 1992’s Whut? Thee Album and 1996’s Muddy Waters) is a treat for fans of funk-driven Hip-Hop, witty undertones and sharp back and forth rhyme schemes. With the majority of their individual and collaboration work produced by Erick Sermon, whose beats were dipped in funk and laced with electronic goodness, and RZA, whose eerie play with strings and movie sound bytes left listeners chillingly applauding, it’s not often you’ll hear a dud from Red or Meth.

In their 2009 web series, The Next 48 Hours With Redman & Method Man, Redman said of the 90s: “It’s a pivotal era in Hip-Hop. I think it was one of the best eras and I wouldn’t trade it for the world. In the 90s you had to be a beast to come out. Your crew had to be thoro to come out. You had to know how to fight when you came out in the 90s. There wasn’t no talking on the internet. We saw you in a spot and blew you out.”

Something else the 90s helped introduce to the world was battles and cyphers. Becoming an exciting new pastime to get stuck into, lunchrooms became battlegrounds, and the ball of a fist and a pencil were all that were needed to provide the instrumental backdrop to the commencement of lyrical warfare. Originally known as the Dozens, its origins span back to slavery times where participants insulted one another until someone gave up. The updated rap version would hear MC’s insult their opposition in rhyme format while their crew looked on. With a similar premise, except this time minus the insults, the cypher saw a group of MCs huddled together rapping back and forth with one another showing off their wordplay, skill and delivery. Acting almost like a rap group, the cypher provided rhyme unity and sparked the interest of those looking for a dose of quick-witted intelligent rhyming.

While names such as Das EFX, Tracey Lee and the Lost Boyz ticked a few boxes for fans of the gritty street style of Hip-Hop that began to take precedent as the leading rap sub-genre, a group of baldheaded rappers from Queens, New York were about to take it so street that their real-life controversies [that mostly involved firearms] were to become Hip-Hop folklore. Onyx, consisting of Sticky Fingaz, Fredro Starr, Big DS – who has since passed away – and Sonsee, were gun-toting hoodlums raised by the streets, introduced to the masses via Run DMC’s Jam Master Jay, and after their first album was put on a world stage by Def Jam Records.

Essentially inventing their own brand of rap music that some called heavy metal rap, stylistically Onyx shouted over bass-heavy beats with subject matters staying in and around gunplay (‘Throw Ya Gunz’) – the group even fired a live gun at the ceiling during their performance at the 1994 Source Awards – and sex (‘Blac Vagina Finda’). With their breakout hit ‘Slam’, the group saw success in their first album, Bacdafucup, going platinum and also beating out Dr. Dre’s The Chronic for Best Rap Album at the 1993 Soul Train Awards. Their second and third albums, All We Got Iz Us and Shut ‘Em Down, whilst not selling as well as their debut, were both showered with an onslaught of critical acclaim.

Continuing to highlight lyricism in a big way both Jeru The Damaja and Group Home were alumni of the Gang Starr Foundation. Celebrated by those who preferred the stripped-down boom bap and sample stylings of production, Jeru’s debut album, The Sun Rises In The East, is to this day still regarded by fans of authentic Hip-Hop as one of the genre’s stand out releases. Released in 1994 and produced entirely by DJ Premier, the album, along with Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), The Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready To Die, and Nas’ Illmatic, contributed to the revival of the east coast Hip-Hop scene. Group Home’s debut album, Livin’ Proof, heard DJ Premier once again provide a rich and rugged musical canvas upon which members Lil’ Dap and Melachi The Nutcracker delivered concise and to the point realities about coming up in both the streets and rap industry.

“If looks could kill you would be an uzi/ You’re a shotgun – bang! What’s up with that thang/ I wanna know how does it hang.” – Salt-N-Pepa ‘Shoop’

The females got it in too during the 90s. The likes of Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown, whose first two albums, Ill Na Na and Chyna Doll, signalled the beginning of a sexually dominant wave that heard women with potty mouths get racy and raunchy on the mic – “He fooled you girl, pussy is power, let me school you, girl,/ Don’t get up off it ’til he move you girl.” That wasn’t it though. Lyrically on-point and not needing to use sex as a weapon, girl power was in full effect long before the Spice Girls thanks to rap’s first female superstar group Salt-N-Pepa.

In a male-dominated genre, Salt-N-Pepa knocked down many doors to become a widely respected rap trio in the late 80s, which in turn opened up Hip-Hop to the idea of female rappers. Choosing to endorse the pop route, their [sometimes] pro-feminist lyrical content and party raps, whilst at times contradictory, were never classed as a gimmick. Instead, the ladies from New York were considered rap pioneers.

One minute expressing their opinion regarding sex in the media on ‘Let’s Talk About Sex’ (taken from the album Blacks’ Magic) and then the next educating the youth on the dangers of sex on the revamped ‘Let’s Talk About Aids’, the talented threesome blew up worldwide thanks to their 1993 album Very Necessary, which featured the smash hits ‘Whatta Man’ and ‘Shoop’, as well as the Grammy Award-winning ‘None Of Your Business’.

Moving away from New York momentarily, there were a few other notable acts garnering attention. The west saw Domino, with his scattershot way of rhyming, schmooze his way through his self-titled 1993 debut. With the smooth hits ‘Getto Jam’ and ‘Sweet Potato Pie’ playing the ying to the popular west coast gangsta rap’s yang, Domino’s vocal rap delivery seemed to borrow its style from Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg and Warren G’s popularised G-Funk sound. Then while New Jersey saw The Fugees begin their rise to world domination with their diamond-selling The Score, Atlanta duo Outkast (Big Boi and Andre 3000) were soon discovered to have one of the best rhyming partnerships in America thanks to a collection of, what some would deem, perfect albums.

Offering a different take on rap, Cleveland’s Bone Thugs-N-Harmony coated their fast-paced words in a melodic shell. Signed by N.W.A.’s Eazy E, Bone specialised in interwoven harmonious singing and rapping long before Drake hit the scene with his half rapping/half-singing delivery. Hitting the top of the charts with their 1995 album E.1999 Eternal, which spawned the Grammy-winning song ‘Tha Crossroads’, their next release, the 1997 double-disc The Art Of War, which featured the much talked about 2Pac assisted ‘Thug Luv’, sold over four million copies and aided the group in proving their superiority as far as their dark rapid-fire style went – ‘Ready 4 War’ took shots at so-called “clones” Do Or Die, Twista, and Three-6-Mafia.

The latter part of the 90s heard the likes of Missy Elliott, P. Diddy (at the time Puff Daddy) and Eminem earn themselves a name before going on to takeover the 2000s, but while 2Pac was clearly winning the popularity contest with his album All Eyez On Me, a down south movement was beginning to take shape and it would soon enough blow up nationally.

Cash Money Records weren’t the only New Orleans powerhouse to put the city on the map. After relocating from the west coast, Master P unveiled a newly branded No Limit Records in 1996. As the label’s main artist, he released the albums Ice Cream Man (1996) – the last with a west coast sound attached to it – and Ghetto D (1997). With the help of producers KLC and Beats By The Pound, whose trigger-happy drum loops and haunting piano riff backdrops caused turmoil in the clubs, P was able to create a similar sound regardless of what artist he assigned to work on it and sell it as part of the No Limit brand as opposed to an individual artist brand. His marketing genius showed its might when making stars of unknowns Mystikal, Fiend, and C-Murder, as well as reigniting Snoop Dogg’s career when his contract was acquired from a then failing Death Row Records.

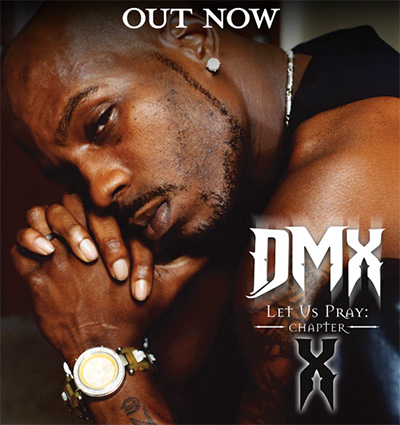

Closing the 90s out on a high, 1998 saw the Ruff Ryders ride off into the sunset in a blaze of glory. With rap’s hottest new prospect DMX barking at anything that moved, representing the Ruff Ryders clique alongside the likes of Eve, Drag-On, and Swizz Beatz, his debut album, It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot, put the same type of raw raps made famous by Onyx back into the homes of the Hip-Hop fan during the shiny suit era (made popular by P. Diddy and Ma$e).

Hitting the top of the Billboard 200 and selling over four million copies, and saving a financially struggling Def Jam in the process, DMX hit the top spot again the same year with his eagerly anticipated Flesh Of My Flesh, Blood Of My Blood. Like something straight out of a twisted nightmare, Swizz Beatz’s keyboard-heavy bangers combined with Dame Grease’s torturous melodies of darkness and church bell sprinklings positioned the Ruff Ryders clique as a rap mainstay with X as their main showpiece.

Hip-Hop in the 90s played out like a Columbian drug deal. It had good product, international appeal, and was very addictive. Lyricism was at the top of the agenda while the boom-bap sound became a part of what many now know as authentic Hip-Hop. Moguls were born, labels became as famous as their artists, and what was considered commercial then is far from what is considered commercial now. With unofficial sub-genres galore: hardcore, pop, conscious, gangsta, and sexually explicit Hip-Hop all clubbed together to offer a little something for everybody. The 90s are often regarded by many as the best era in Hip-Hop, and whilst it’s an arguable point, when you’ve got so much to choose from, not too many copycats, and the ability to witness a culture grow the way it did in the 90s, why would you even bother arguing the case?