Dreaming Of The Delta – The Transatlantic Blues Revolution

The Blues played a pivotal role in the creation of what we have come to call rock music. As Muddy Waters famously said, “The Blues had a baby and they named it rock’n’roll.”

In Britain, the music that became known as skiffle was a catalyst for change and an inspiration for many young British teenagers… John Lennon, for one. It was almost as though, for the first time, British teenagers could have their own music, not a rehash of music their parents liked and approved of. Skiffle was also home-grown, nurtured by the “jazz crowd”, the very same people that championed the blues in Britain.

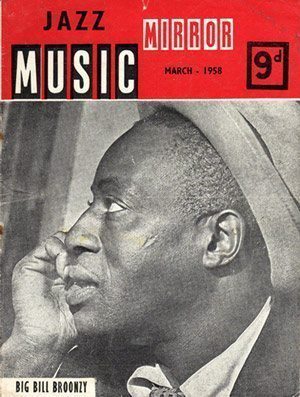

In September 1951, a poster advertising the first London concert by Big Bill Broonzy, following ones he had already given in Paris, clearly positions the blues, as very much a part of the jazz world. The “recital”, as it was called, was promoted by The London Jazz Club, and the reason for it being held was the growing interest that had blossomed in the 40s, through men like Paul Oliver, the noted British blues writer. He wrote of the “Rhythm Clubs”, for blues and jazz collectors, held in rented schoolrooms in South Harrow and Watford.

In September 1951, a poster advertising the first London concert by Big Bill Broonzy, following ones he had already given in Paris, clearly positions the blues, as very much a part of the jazz world. The “recital”, as it was called, was promoted by The London Jazz Club, and the reason for it being held was the growing interest that had blossomed in the 40s, through men like Paul Oliver, the noted British blues writer. He wrote of the “Rhythm Clubs”, for blues and jazz collectors, held in rented schoolrooms in South Harrow and Watford.

In the late 40s, the Jazz Appreciation Society persuaded British Brunswick label to release some blues recordings, including the brilliant ‘Drop Down Mama’ and ‘Married Woman Blues’, by Sleepy John Estes.

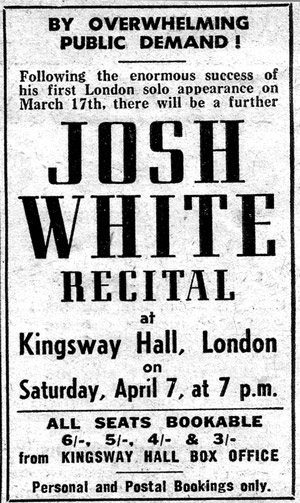

Come the 50s, and both American folklorist Alan Lomax and Melody Maker’s Max Jones were giving occasional talks on BBC radio about the blues. On Friday evenings, Harry Parry’s Radio Rhythm Club sometimes played blues records, like Josh White’s ‘House Of The Rising Sun’, another release on Brunswick. Slowly, the blues was capturing the imagination of a small minority of British youth. While, in all truth, they had a somewhat romantic notion about the music, the important thing is they had any notion at all: black music had found champions in Britain.

Shortly before Broonzy’s visit, Josh White appeared in the UK, singing his “easy” blend of the blues; around the same time, Lonnie Johnson made the trip across the Atlantic. All three came from the more sophisticated, urban blues scenes of Chicago and New York.

In early summer 1952, Melody Maker reviewed recordings by Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker, as well as Sonny Boy Williamson I and Leroy Carr (whose records were receiving belated British release). While Melody Maker was essentially a jazz paper that took itself very seriously, its coverage of the blues helped elevate the music to a more serious level than mere pop music.

As the decade wore on, a transatlantic trickle of artists appeared in Britain. Billie Holiday visited in early 1954, followed, a couple of years later, by Jimmy Rushing and Joe Williams. There were return visits by Broonzy, accompanied by Brother John Sellers, as well as the white folk blues player Ramblin’ Jack Elliott.

As the decade wore on, a transatlantic trickle of artists appeared in Britain. Billie Holiday visited in early 1954, followed, a couple of years later, by Jimmy Rushing and Joe Williams. There were return visits by Broonzy, accompanied by Brother John Sellers, as well as the white folk blues player Ramblin’ Jack Elliott.

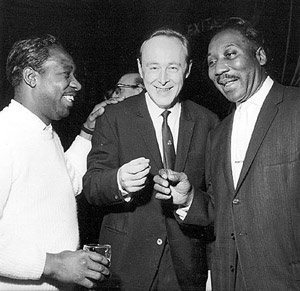

Jazz bandleader Chris Barber was a key figure in popularising the blues in Britain. In April 1958, “America’s foremost folk blues singers” accompanied Barber on a nationwide tour. Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee played London’s Royal Festival Hall to an excellent response from an audience who were probably more appreciative than an American one would have been. A few months later, Barber arranged for Muddy Waters, along with Otis Spann, to play at a festival in Leeds which was followed by a week-long UK tour. Ironically, some audiences asked Muddy to turn his amplifier down, as they were more attuned to the blues of Muddy’s mentor, Big Bill Broonzy, and because jazz was not amplified in the clubs.

According to Mike Vernon, founder of the Blue Horizon label, “Club promoters would take the acts because Chris Barber was a saleable commodity. So Chris’ love of the blues was able to bring in those people, and the promoters never argued.”

Over in America, Chuck Berry played the Newport Jazz Festival. The press accused him of being “disgraceful’, while in Britain, the New Musical Express (NME) wrote, “Berry is part of the context of the blues as they are now.” Berry’s ‘Sweet Little Sixteen’ had just spent five weeks on the UK singles chart; an awful lot of young white guitarists were suitably impressed.

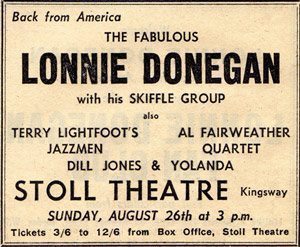

C hris Barber’s popularity in Britain can be placed into context by the 1958 New Musical Express poll that placed him at No.2 in the “small groups” category. The winner, however, was Lonnie Donegan.

hris Barber’s popularity in Britain can be placed into context by the 1958 New Musical Express poll that placed him at No.2 in the “small groups” category. The winner, however, was Lonnie Donegan.

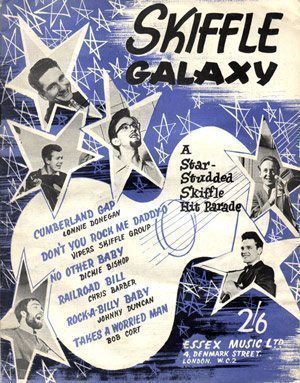

Two years earlier, a Melody Maker headline emblazed across the top of a schedule asked the question: “Skiffle or Piffle?” The article was written by Alexis Korner, and was a description of the British skiffle craze. “In 1952, shortly after Ken Colyer’s return from New Orleans, the first regular British skiffle group was formed to play in the intervals at the Bryanston Street Club. This group consisted of Ken Colyer, Lonnie Donegan and I playing guitars, Bill Colyer on washboard and Chris Barber or Jim Bray playing string bass.” Korner went on to criticise skiffle for introducing a vocal element, saying it was “a commercial success, but musically it rarely exceeds the mediocre”.

Whatever Korner’s opinion, there is no doubting skiffle’s influence on (British) music, or the success of its first superstar, Lonnie Donegan. Between 1956 and 1962, Lonnie had 30 British hit singles and topped the charts three times, with 14 other singles making the Top 10. His first hit, ‘Rock Island Line’, made the US Top 10 in 1956, a rare achievement for a British record. Glasgow-born, Donegan recorded remakes of blues or folk songs such as Lead Belly’s ‘Rock Island Line’, ‘Bring A Little Water Sylvie’ and ‘Pick A Bale Of Cotton’, as well as Woody Guthrie’s, ‘Gamblin’ Man’ and ‘Dead Or Alive’.

Whatever Korner’s opinion, there is no doubting skiffle’s influence on (British) music, or the success of its first superstar, Lonnie Donegan. Between 1956 and 1962, Lonnie had 30 British hit singles and topped the charts three times, with 14 other singles making the Top 10. His first hit, ‘Rock Island Line’, made the US Top 10 in 1956, a rare achievement for a British record. Glasgow-born, Donegan recorded remakes of blues or folk songs such as Lead Belly’s ‘Rock Island Line’, ‘Bring A Little Water Sylvie’ and ‘Pick A Bale Of Cotton’, as well as Woody Guthrie’s, ‘Gamblin’ Man’ and ‘Dead Or Alive’.

Backed on some dates by The Johnny Burnette Trio, Donegan toured America in 1956, appearing on Perry Como’s TV show, as well as performing with Chuck Berry. Though Donegan’s was the first skiffle hit, his was not the first skiffle release. In mid-1955, Ken Colyer’s group, with Alexis Korner on guitar, released Lead Belly’s ‘Take This Hammer’.

Donegan’s success was surpassed in 1957 when ‘Cumberland Gap’ and ‘Gamblin’ Man’ both made No.1. By the end of the year, skiffle was on the wane: for groups such as Chas McDevitt’s Skiffle Group, featuring Nancy Whisky, The Vipers Skiffle Group and Tennessee-born Johnny Duncan and his Blue Grass Boys’, their moment of glory was over.

This do-it-yourself musical craze – a proto-rock’n’roll – was, however, an inspiration. Skiffle made it possible for thousands of young Brits to emulate their heroes… anyone could be a pop star. Everybody in the 60s rock bands like The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles started off by playing this brand of homemade blues.

This do-it-yourself musical craze – a proto-rock’n’roll – was, however, an inspiration. Skiffle made it possible for thousands of young Brits to emulate their heroes… anyone could be a pop star. Everybody in the 60s rock bands like The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles started off by playing this brand of homemade blues.

One day in late spring 1958, five young men recorded a 78rpm record at an electrical shop in Liverpool. This group called themselves The Quarry Men, and included John Lennon, George Harrison and Paul McCartney. As Paul later said, “John was singing ‘Down, down, down to the penitentiary.’ He was filling in with blues lines. I thought that was good.”

Skiffle was effectively finished by early 1958. Though Lonnie Donegan continued to have hits, novelty songs were increasingly his forte. Britain, like America, was firmly in the grip of rock’n’roll: Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly And The Crickets and The Everly Brothers all had British hits in 1958 and 1959. In the closing years of the 50s, the British charts were a mix of American rock’n’rollers and traditional artists such as Frank Sinatra and Perry Como, along with a new phenomenon: British “copy cat” rock’n’rollers, like Tommy Steele, Marty Wilde, Cliff Richard and Adam Faith, covered American hits, as well as performing British material.

But the real blues seemed set to remain the preserve of jazz aficionados. Paul Oliver continued to champion the cause, while Chris Barber and others arranged infrequent short tours by a handful of bluesmen. Champion Jack Dupree visited Britain in 1959, and in the following year Memphis Slim, Roosevelt Sykes, James Cotton, Little Brother Montgomery and Jesse Fuller all crossed the Atlantic.

Most visiting Americans played at a club started by Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies. With Korner on guitar and Davies on harmonica, they performed their own brand of country blues at the London Blues And Barrelhouse Club, which was held in a pub. They also worked with Chris Barber’s Band, playing a blues segment with Ottilie Patterson (Barber and Patterson married in 1959). Barber continued to champion the blues in his recordings, releasing an album in 1960 entitled Chris Barber’s Blues Book, which featured classic blues tunes like Jim Jackson’s ‘Kansas City Blues’ and Leroy Carr’s ‘Blues Before Sunrise’.

Most visiting Americans played at a club started by Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies. With Korner on guitar and Davies on harmonica, they performed their own brand of country blues at the London Blues And Barrelhouse Club, which was held in a pub. They also worked with Chris Barber’s Band, playing a blues segment with Ottilie Patterson (Barber and Patterson married in 1959). Barber continued to champion the blues in his recordings, releasing an album in 1960 entitled Chris Barber’s Blues Book, which featured classic blues tunes like Jim Jackson’s ‘Kansas City Blues’ and Leroy Carr’s ‘Blues Before Sunrise’.

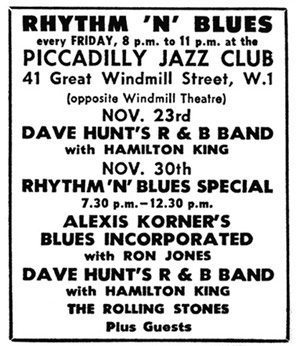

In 1961, Korner, who was half-Greek and half-Austrian, and Davies formed Blues Incorporated. With its harder-edged blues sound and residency at the Ealing Rhythm And Blues Club, they become a nursery for aspiring talent keen on playing the blues… a few thousand miles from its Delta home.

In late 1961, 19-year-old Brian Jones watched Korner playing with Chris Barber’s Band at Cheltenham Town Hall. A few months later, on 17 March 1962, Brian hitchhiked to London to see Blues Incorporated at the Ealing club. Besides Korner and Davies, there was Dave Stevens on piano, Andy Hoogenboom on bass, Dick Heckstall-Smith on tenor sax and a jazz-loving drumming named Charlie Watts. It was to change Brian’s life – and alter the musical map of the world.

On 5 October 1962, a few months after The Rolling Stones made their debut at the Marquee Club, The Beatles released their debut single, ‘Love Me Do’. In January 1963, with British popular music in the first flush of radical change, Blues Incorporated made their BBC TV debut, on The 6.25 Show. Prior to The Beatles’ emergence, the 60s charts were much like they were at the end of the 50s: It was all about Cliff Richard, Elvis, The Shadows, Del Shannon, Mark Wynter and Marty Robbins, though Frank Ifield topped the charts with a remake of Hank Williams’ 1949 hit, ‘Lovesick Blues’.

According to John Lennon: “I had a friend who was a blues freak, he turned me on to the blues. It added the real blues to my consciousness.” And in the wake of The Beatles’ success, British record companies set about signing any “beat” group they could, especially if they came from Liverpool. Liverpool’s penchant was for R&B, whereas London was the blues capital of the UK. However, it wasn’t just Liverpool that attracted record company scouts. Manchester, Birmingham and Newcastle all became magnets for the A&R men.

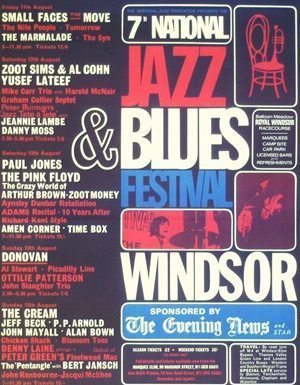

In late April, The Beatles went to see the Stones at Richmond’s Crawdaddy Club, and soon after they signed to Decca Records. A few months later, in August 1963, the National Rhythm And Blues Festival took place at Richmond in Surrey. The bill was entirely British and included, Chris Barber, The Graham Bond Quartet, Cyril Davies, Long John Baldry, Georgie Fame and The Rolling Stones.

In late April, The Beatles went to see the Stones at Richmond’s Crawdaddy Club, and soon after they signed to Decca Records. A few months later, in August 1963, the National Rhythm And Blues Festival took place at Richmond in Surrey. The bill was entirely British and included, Chris Barber, The Graham Bond Quartet, Cyril Davies, Long John Baldry, Georgie Fame and The Rolling Stones.

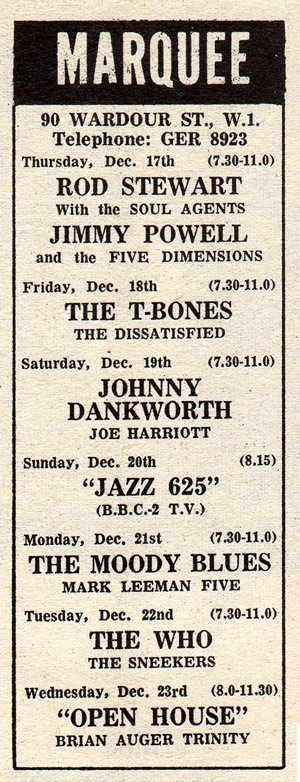

As 1963 became 1964, the Stones were riding high on the UK singles chart with ‘I Wanna Be Your Man’, a song written by Lennon and McCartney. 1964 was to be the year that the Stones first topped the charts; it was also the year that bona fide blues records by black artists made the UK singles chart. Howlin’ Wolf’s ‘Smokestack Lightning’ entered the chart in early June 1964.

A week after the Stones charted, John Lee Hooker’s ‘Dimples’, originally cut for Vee-Jay in 1956, spent the rest of the summer in the lower reaches of the chart. The week after Hooker charted, he supported the Stones at a gig at in Magdalen College, Oxford. Four days later, Hooker and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers played with the Stones at an all-nighter at London’s Alexandra Palace. Hooker also got the chance to appear on the TV’s, Ready Steady Go!, just another small step for the blues becoming a more prominent feature on the British music scene.

All sorts of artists were finding their inspiration in the blues: Billy Fury cut Jimmy Reed’s ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’, Tommy Bruce released ‘Boom Boom’, The Animals got to No.1 with ‘House Of The Rising Sun’, a song they may well have heard Josh White singing on the BBC.

All sorts of artists were finding their inspiration in the blues: Billy Fury cut Jimmy Reed’s ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’, Tommy Bruce released ‘Boom Boom’, The Animals got to No.1 with ‘House Of The Rising Sun’, a song they may well have heard Josh White singing on the BBC.

The Zombies’ ‘She’s Not There’ got to No.12 in late summer. Neither the group – with Colin Blunstone’s angelic vocals – nor the song are the blues; however, as Rod Argent, the group’s keyboardist and the song’s writer, revealed, “If you play John Lee Hooker’s song ‘No One Told Me’ from The Big Soul Of John Lee Hooker album, you’ll hear him sing, ‘No one told me it was just a feeling I had inside.’ There’s nothing in the melody or the chords that’s the same, it was just that little phrase.”

Richard Barnes, who went to art college with Pete Townshend, and was the man who suggested a new name for Townshend’s band, The Zoot Suits, recalled, “What they knew, they played. And they played them every night – just like most bands at the time.” Shortly after becoming, The Who, the group’s manager persuaded them to record a number he had “written” – and to also change their name once more. For a brief time in 1964, The ’Oo became The High Numbers and released ‘I’m The Face’, a song based very firmly on Slim Harpo’s ‘Got Love If You Want It’.

Richard Barnes, who went to art college with Pete Townshend, and was the man who suggested a new name for Townshend’s band, The Zoot Suits, recalled, “What they knew, they played. And they played them every night – just like most bands at the time.” Shortly after becoming, The Who, the group’s manager persuaded them to record a number he had “written” – and to also change their name once more. For a brief time in 1964, The ’Oo became The High Numbers and released ‘I’m The Face’, a song based very firmly on Slim Harpo’s ‘Got Love If You Want It’.

Many bands released blues singles, some of which were covers of Chicago’s finest post-war recordings. During 1964, Dave Berry & The Cruisers released ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’, The Sheffields recorded Muddy Waters’ ‘Got My Mojo Working’, The Spencer Davis Group recorded Hooker’s ‘Dimples’, The Yardbirds recorded ‘I Wish You Would’, Rod Stewart remade the classic ‘Good Morning Little Schoolgirl’ and the Stones did Wolf’s ‘Little Red Rooster’, which topped the UK charts. These are just a handful of countless blues covers recorded by aspiring British blues bands.

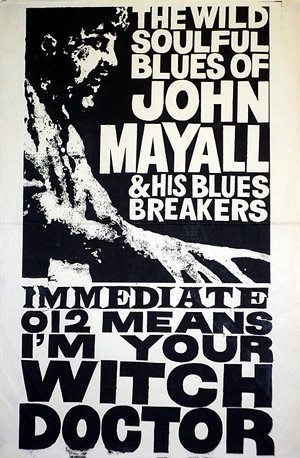

In April 1965, Eric Clapton quit The Yardbirds to join John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. Mayall was a somewhat unlikely “pop star”: for a start, he was over 30! In 1963, he formed The Bluesbreakers, a band that has probably had more line-ups than any other in the history of modern music. They were spotted by a Decca staff producer, Mike Vernon, who persuaded the label to sign the band. The Bluesbreakers’ first single, ‘Crawling Up The Hill’ coupled with ‘Mr James’, was released in April 1964. Playing bass with Mayall was John McVie, and by the time Clapton joined, in October 1965, Hughie Flint was filling in on drums. Early the next year they cut the brilliant album Bluesbreakers With Eric Clapton. While it proved to be a breakthrough, it wasn’t long before Clapton left, to be replaced by Peter Green,

Flint had also moved on, and was replaced by Aynsley Dunbar. More excellent albums followed and, by early 1967, Mayall had one of the premier blues outfits in Britain. Their repertoire consisted of Mayall originals, coupled with classic blues like ‘Dust My Broom’, or Otis Rush’s ‘So Many Roads’ and ‘Double Trouble’. By mid-1967, Mick Fleetwood was playing drums, but he, along with Green and McVie, soon departed The Bluesbreakers to form Fleetwood Mac. Within no time, Mayall was back in the studio with a new guitar-slinger, Mick Taylor, along with Keef Hartley on drums. Space restricts us from continuing the story of Mayall’s many and varied line-ups…

Flint had also moved on, and was replaced by Aynsley Dunbar. More excellent albums followed and, by early 1967, Mayall had one of the premier blues outfits in Britain. Their repertoire consisted of Mayall originals, coupled with classic blues like ‘Dust My Broom’, or Otis Rush’s ‘So Many Roads’ and ‘Double Trouble’. By mid-1967, Mick Fleetwood was playing drums, but he, along with Green and McVie, soon departed The Bluesbreakers to form Fleetwood Mac. Within no time, Mayall was back in the studio with a new guitar-slinger, Mick Taylor, along with Keef Hartley on drums. Space restricts us from continuing the story of Mayall’s many and varied line-ups…

After Clapton’s departure from The Bluesbreakers, he joined Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker to form Cream in 1966. Steeped as they all were in the blues, the trio became the archetypal blues-rock band, covering the songs of the Delta greats in an inventive and original way. They also became the model of the powerhouse rock trio, producing exciting extended reworkings of classic Delta blues cuts, including ‘I’m So Glad’ (Skip James), ‘Crossroads’ (Robert Johnson), ‘Spoonful’ (Howlin’ Wolf) and ‘Outside Woman Blues’ (Blind Joe Reynolds). So convincing were they that many of their audience had little or no idea that these songs were 30 years old or more – not that Cream sought to fool anyone.

When McVie, Fleetwood and Green graduated from Mayall’s blues academy they could have had little or no idea of their future. Fleetwood Mac’s debut was at the Windsor Jazz And Blues Festival in August 1967, with Bob Brunning playing bass. Their first single, a cover of Elmore James’ ‘I Believe My Time Ain’t Long’, was credited to Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac and came out in November, by which time McVie had replaced Brunning. The band loved the blues, Green hero-worshipped BB King, and Spencer loved Elmore James. It made for a powerful combination.

When McVie, Fleetwood and Green graduated from Mayall’s blues academy they could have had little or no idea of their future. Fleetwood Mac’s debut was at the Windsor Jazz And Blues Festival in August 1967, with Bob Brunning playing bass. Their first single, a cover of Elmore James’ ‘I Believe My Time Ain’t Long’, was credited to Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac and came out in November, by which time McVie had replaced Brunning. The band loved the blues, Green hero-worshipped BB King, and Spencer loved Elmore James. It made for a powerful combination.

The Stones, Cream, Fleetwood Mac and countless other British bands were all steeped in the blues and, as time went on, they all played a pivotal role in the creation of what we have come to call rock music. As Muddy Waters famously said, “The Blues had a baby and they named it rock’n’roll.” In no small way, this was down to the foster care that the blues received from young British white boys who dreamed of the Mississippi Delta, Chicago’s Maxwell Street and the clubs of the city’s South Side.