Back For Good: How Boy Bands Made It To The Top

The very idea of a group of young men singing together in harmony has been the bedrock of pop music for as long as young people have been buying records.

The dictionary definition of “boy band” is: “A pop group composed of attractive young men, whose music and image are designed to appeal primarily to a young teenage audience.” A suitably vague description, then, that could encompass anyone from The Beatles to Maroon 5. Down the years, the term itself has gone in and out of fashion. Its meaning has changed over the decades too, but the notion of a musical group made up of attractive young men has never gone out of style.

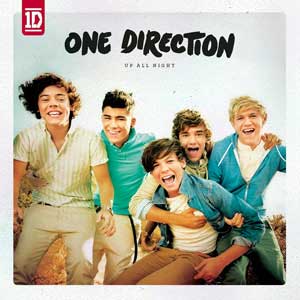

But what exactly do we mean when we talk about boy bands? Surely Maroon 5, for example, fit the description? The band came into being when the founder members were still in high school, after all – and there’s no denying that both their image and music appeals to a young teenage audience. After all, ‘Moves Like Jagger’ was a huge summer smash in 2011, and featured another onetime teen star in Christina Aguilera. But few of the band’s millions of fans would use that term to describe them, preferring to think of their idols as rock stars. Similarly, the group also has crossover appeal to an older audience – but then so do One Direction. So what is a boy band, and where did they come from in the first place?

The very idea of a group of young men singing together in harmony has been the bedrock of pop music for as long as young people have been buying records. Four boys moving as one, each with his own distinct talents and charms, is an idea that followed the US gospel quartet singers of the Deep South north to places like Chicago and New York City, where groups of teenagers would hang out under street lamps on the corner, endlessly practicing their four-part harmonies, known as doo-wop due to the non-lyrical nature of many of the vocal parts.

Today, such groups of charming young men are known as “boy bands” – a term used as often in derision as in definition. Supposedly “manufactured” groups that emerge from talent shows like X Factor are lumped in with bands assembled “the old-fashioned way” – namely, a group of friends coming together in their teens, dreaming of seeing their collective name in lights. Critics often demean such outfits, giving them the tag of “boy band” by way of casting them aside from what they consider more worthy offerings. They’re not real bands, is the implication, and have no place alongside the rich history of pop music that has spawned a vast industry – not to mention a form of art in its own right. But such assertions demonstrate an ignorance of the true story of the boy band in pop music.

The celebrated English diarist Samuel Pepys was himself a keen amateur musician, and in his diaries he wrote of making “barber’s music”, an instrumental music made with one’s companions. Historically, barber’s shops were communal places, and Pepys’ is an early reference to what grew into “barbershop music”. During the 19th Century, this style of close-harmony vocal music grew in popularity among African-Americans, who sang spirituals as well as popular folk songs. The advent of recorded music saw this style adopted by white minstrel groups.

Male vocal harmony groups became a mainstay of the burgeoning music industry, and gave birth to many of its greatest early stars. In 1935, a young Frank Sinatra joined a trio of singers, The 3 Flashes, to form The Hoboken Four, finding success on the popular Major Bowes Amateur Hour radio show. However, Sinatra never really gelled with the other three and strode out on his own. But the fact that he saw harmony groups as a route to success that demonstrates their importance.

Perhaps the most popular group of the 30s and 40s were The Ink Spots, a four-piece consisting of clean-cut black Americans who had hits with ‘Whispering Grass (Don’t Tell the Trees)’ and ‘Memories Of You’. Journalist John Ormond Thomas described them in a 1947 issue of Picture Post magazine: “Eight trouser-legs, creased and caught in time, flicker with legs inside them, moved by melancholy mood. Eight hands gesticulate faintly but with an abundance of variation. Eight arms express restrained wild-rhythm. Eight lips savour every lyric-rhyme.” Excepting for numerical variation, he could have been describing anyone from The Ink Spots through Jackson 5 to Backstreet Boys, such is the eternal appeal of the boy band.

But despite the popularity of vocal harmony groups, record companies still sought the star. Whether it was Sinatra, Bing Crosby or Elvis Presley, that one face on the cover of a magazine was gold. Until that is, those four lads from Liverpool made the desire for four (or three or five) charismatic young men the ultimate aim.

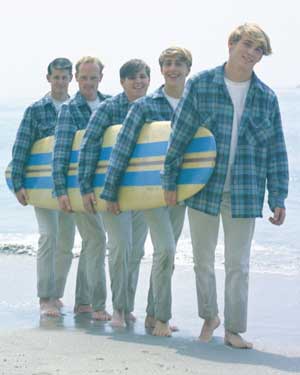

The unprecedented popularity of The Beatles, and those who followed in their wake, such as The Rolling Stones and The Beach Boys (themselves born out of America’s vocal-harmony tradition, as fans of barbershop quartet The Four Freshmen), changed the face of the music industry forever. Hereafter, every label tried to sign its own hit-making group of young men.

The unprecedented popularity of The Beatles, and those who followed in their wake, such as The Rolling Stones and The Beach Boys (themselves born out of America’s vocal-harmony tradition, as fans of barbershop quartet The Four Freshmen), changed the face of the music industry forever. Hereafter, every label tried to sign its own hit-making group of young men.

In 1966, the US TV network NBC went one step further, assembling its own band from a series of auditions. The idea of manufacturing a band was a revolutionary move. By distilling the essence of what made a hit group, NBC had opened up a whole new way of making pop music. Yet, despite the network’s aims to control the four actor-musicians, The Monkees soon attained counter-culture credibility, and have since gone on to sell something in the region of 75 million records in a career spanning 50 years.

Fictional bands were always going to be a novelty – there was even a cartoon band, The Archies, who had a smash hit with ‘Sugar, Sugar’ in the late 60s – but the principle of assembling a band to a blueprint for success continues to be both popular and successful to this day. Managers, impresarios and producers had long sought out that individual with a certain, indefinable star quality, but once bands had established themselves as here to stay, they sought the magic formula for finding a group of young boys and adjusting their image to appeal to a mass audience.

Liverpool businessman Brian Epstein struck gold when a young man called Raymond Jones walked into his NEMS record store enquiring about a local act known as The Beatles. Epstein sought them out but thought their rugged, leather look and unprofessional stage demeanor would keep from hitting the big time. By putting them in smart suits and setting restrictions on their stage behavior – no smoking, swearing or eating bags of chips – he gave them an image that was easy to sell to a wide audience. But as the 60s gave way to the 70s, it was time for a new generation to take over – and this time they were starting young.

Founded in the late 50s by Berry Gordy, Motown Records styled itself as “The Sound Of Young America”. Though many of Motown’s stars were solo singers such as Little Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye, the label had many of its biggest hits with the group vocal format. Gordy had migrated north to Detroit from Georgia, and so was rooted in the southern tradition of gospel quartets – four-part harmony sung by groups of young men. Motown had huge success with Four Tops, The Temptations and The Miracles during the 60s, but as the 70s dawned, an even younger group would see the label’s successes continue into the new age.

The Jackson brothers had been singing together for a number of years by the time Gordy finally signed them to Motown in 1969. Their first single for the label, ‘I Want You Back’, topped the Billboard Hot 100 in January 1970 – replacing The Beatles’ final single, ‘Let It Be’, at the top of the charts, and in doing so marking a change of service at pop’s top table. Jacksonmania took hold and saw Jackie, Tito, Jermaine, Marlon and little Michael’s images emblazoned on everything from magazine covers and posters to lunchboxes and even a Saturday morning cartoon show – not a million miles away from The Archies. The group would have continued success into the 80s, but were ultimately usurped by one of their own. Motown quickly launched Michael as a star in his own right, with 1971’s ‘Got To Be There’ the first of a seemingly endless string of hits that continues today, years after the so-called King Of Pop’s untimely death in 2009.

The Jackson brothers had been singing together for a number of years by the time Gordy finally signed them to Motown in 1969. Their first single for the label, ‘I Want You Back’, topped the Billboard Hot 100 in January 1970 – replacing The Beatles’ final single, ‘Let It Be’, at the top of the charts, and in doing so marking a change of service at pop’s top table. Jacksonmania took hold and saw Jackie, Tito, Jermaine, Marlon and little Michael’s images emblazoned on everything from magazine covers and posters to lunchboxes and even a Saturday morning cartoon show – not a million miles away from The Archies. The group would have continued success into the 80s, but were ultimately usurped by one of their own. Motown quickly launched Michael as a star in his own right, with 1971’s ‘Got To Be There’ the first of a seemingly endless string of hits that continues today, years after the so-called King Of Pop’s untimely death in 2009.

A song intended for Jackson 5 would provide the launch pad for another of the early 70s’ biggest boy bands. George Jackson’s ‘One Bad Apple’ was turned down by Gordy for his fab five, so George took it to MGM for their “white Jacksons”. The Osmonds, like their African-American counterparts, were another family group who had been singing together for years. As with the Jacksons, the Osmonds were born out of their own cultural tradition, in their case barbershop harmony singing once more showing its influence. Their own phenomenal success saw the band embrace elements of the ongoing rock’n’roll revival and glam rock, with hits such as ‘Crazy Horses’ whipping their fans into a frenzy that was dubbed Osmondmania. And, in another parallel with their contemporaries, the group’s success launched the solo career of its star, Donny, as well as spin-off careers for little Jimmy and their sister Marie.

If the 70s was the petri dish that nurtured what we now think of as the boy band phenomenon, then the 80s would see them come to fruition on never-before-imagined levels.

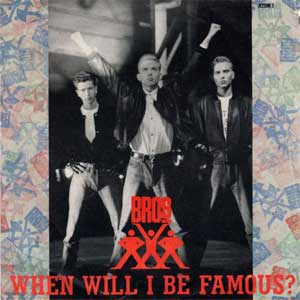

The decade’s early years saw many pop groups emerge from the post-punk/new romantic scene, with acts such as Adam And The Ants, Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet fulfilling the criteria of presenting attractive young men in a professional way to appeal primarily to young teenagers. But would any of these be called a boy band? Probably not. So what is it that sets them apart from an act like Bros, who found huge success in the UK and Europe in the latter half of the decade?

What makes one act credible and another shunned by the critics is a matter that has baffled for generations. Is it simply that Duran Duran were better than Bros, or is there more to it than that? Was it that Duran Duran had worked the clubs and came from a recognised scene, whereas Bros were viewed as having had their success manipulated by an established manager (Tom Watkins, who also looked after Pet Shop Boys)? Is the difference mere snobbery, or does a perceived artistic value trump pure pop sensibility in the eyes of the critics?

What makes one act credible and another shunned by the critics is a matter that has baffled for generations. Is it simply that Duran Duran were better than Bros, or is there more to it than that? Was it that Duran Duran had worked the clubs and came from a recognised scene, whereas Bros were viewed as having had their success manipulated by an established manager (Tom Watkins, who also looked after Pet Shop Boys)? Is the difference mere snobbery, or does a perceived artistic value trump pure pop sensibility in the eyes of the critics?

Whatever the critics may have thought, boy bands were here to stay. As the 90s dawned, New Kids On The Block were determined to hold onto their crown as the world’s top boy band, but challengers were lining up. Motown continued their long-running history with the format with the African-American quartet of R&B harmony singers, Boyz II Men. By mixing hip-hip-influenced beats with classic soul harmonies, the group had near-universal appeal. Their 1992 single ‘End Of The Road’ set a new record, holding the No.1 spot on the Billboard chart for 13 weeks – a record they beat time and again in a career that continues today, a quarter of a century later.

That Boyz II Men have spent more weeks on the top of the charts than almost anyone else in pop history is testament to the enduring popularity of such artists. While in their infancy, many so-called boy bands are given short shrift by the critics, and yet so many of them have careers that long outstrip most of the supposedly hip bands beloved of their detractors. Of course, much of this is down to adaptability. In any field of music, the artists who are most able to adapt and move with the times are the ones who will achieve longevity.

Meanwhile, in Manchester, Nigel Martin-Smith sought to emulate the success of Stateside acts such as New Kids On The Block, and, having already recruited the talented young songwriter Gary Barlow, he set about building what he hoped would be the world’s biggest boy band. The resultant Take That featured Barlow alongside Robbie Williams, Jason Orange, Mark Owen and Howard Donald. From 1990-96, they would have a level of success in the UK and Europe that brought comparisons with Beatlemania. When they split in 1996, a special telephone helpline was set up to counsel stunned fans. But with Barlow, Owen and Williams all enjoying solo success – the latter to rival that of the band – their faces were rarely out of the limelight. The band would reunite in 2006 to arguably bigger acclaim than in their first incarnation, and continue as a three-piece today.

In their wake, Boyzone were another huge band in the British Isles. In a strange twist, their singer, Ronan Keating, became joint manager of Westlife, a band created in Boyzone’s image, and who would copy their success.

However, despite Martin-Smith’s best intentions, Take That, along with Boyzone and Westlife, rarely saw the same level of fame in the United States, where another vocal group was lining up for the kind of success he could only have dreamed of. Backstreet Boys were formed in Florida in 1993, and became a global sensation with the 1996 release of their eponymous debut album. The following 20 years have seen them become the biggest-selling boy band in history, with reported sales of 165 million records globally – more than double almost all of their predecessors.

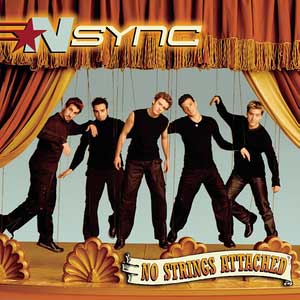

Another Florida act continued the boy band tradition of being a stepping stone to solo success. Born out of the auditions for Backstreet Boys, NSYNC also launched themselves with a single called ‘I Want You Back’, in 1996, but it would be another four years later before they had their No.1 Billboard hit, ‘It’s Gonna Be Me’. The single was taken from the band’s second album, No Strings Attached, which sold a reported 2.4 million copies in its first week. The appeal of the boy band was showing no signs of waning. But NSYNC may yet end up best known for providing a platform for Justin Timberlake, who, since leaving the band, has enjoyed extraordinary success in both music and cinema.

Another Florida act continued the boy band tradition of being a stepping stone to solo success. Born out of the auditions for Backstreet Boys, NSYNC also launched themselves with a single called ‘I Want You Back’, in 1996, but it would be another four years later before they had their No.1 Billboard hit, ‘It’s Gonna Be Me’. The single was taken from the band’s second album, No Strings Attached, which sold a reported 2.4 million copies in its first week. The appeal of the boy band was showing no signs of waning. But NSYNC may yet end up best known for providing a platform for Justin Timberlake, who, since leaving the band, has enjoyed extraordinary success in both music and cinema.

Into the 21st Century, boy bands are more likely to be born out of talent shows, such as X Factor. One Direction may have finished in third place in the 2010 series of Simon Cowell’s hit factory show, but they’ve since gone on to sell millions of records across the world. They were the first band ever to see their first four albums enter the Billboard chart at No.1, and are reported to have fronted the highest-grossing tour ever staged by a male vocal harmony group.

Surely the success of acts such as One Direction and Backstreet Boys proves that, if anything, the boy band phenomena is still growing. And yet we’re still no closer to getting to the bottom of that definition. Maroon 5 still fit the bill in many ways – but then so do The Beatles. Or The Jonas Brothers. Nobody would dispute that Take That were a boy band – despite a career selling albums that have regularly received both commercial and critical acclaim. Ultimately, the reputation of each band rests on the quality of their music, and their ability to adapt. Each act lives and dies on its own merit, so whether we think of them as boy bands or not, in the general scheme of things, matters not a jot. All we know for sure is that, before long, there will be another gang of attractive young men, whose music and image will be designed to appeal primarily to a young teenage audience.

Surely the success of acts such as One Direction and Backstreet Boys proves that, if anything, the boy band phenomena is still growing. And yet we’re still no closer to getting to the bottom of that definition. Maroon 5 still fit the bill in many ways – but then so do The Beatles. Or The Jonas Brothers. Nobody would dispute that Take That were a boy band – despite a career selling albums that have regularly received both commercial and critical acclaim. Ultimately, the reputation of each band rests on the quality of their music, and their ability to adapt. Each act lives and dies on its own merit, so whether we think of them as boy bands or not, in the general scheme of things, matters not a jot. All we know for sure is that, before long, there will be another gang of attractive young men, whose music and image will be designed to appeal primarily to a young teenage audience.

The career-spanning 5LP Maroon 5 box set, Maroon 5: The Studio Albums is due for release on 30 September and can be ordered here: