Know Your Writes – How Music Writers Inspire Us To Listen

During a prickly 1977 interview with a Toronto Star staff reporter Bruce Kirkland, the late Frank Zappa aired his views on music critics, candidly stating: “Most rock journalism is people who can’t write interviewing people who can’t talk for people who can’t read.”

Zappa’s harsh quote later polarised opinion when it appeared in Rolling Stone’s syndicated ‘Loose Change’ column, but then the wider public’s view of rock music writers and their abilities has vacillated for decades now. Some still believe music writing to be a romantic vocation where fortunate writers are blessed with unqualified access to rock stars and their inner circles, yet most seasoned-writers would say it’s anything but glamorous.

Nonetheless, an inherent desire to write words on music seemingly overrides either personal gain or sometimes even an individual’s health. This apparently uncontrollable urge has persuaded successive generations of writers to pick up a pen and, if anything, the arrival of the internet has encouraged a far greater legion of wannabe authors to share opinions online. So the million-dollar question remains: what is this indefinable force that drives us to write about music in the first place?

According to The Guardian’s respected music columnist Alex Petridis, it’s the content of the music itself that fires people up. “I think music is important: it deserves to be discussed and evaluated properly, and no one’s come up with a better way of doing it,” he wrote. “The rise of the internet may mean there’s no such thing as a definitive album review anymore, but that doesn’t matter… the more people discussing and evaluating, the better.”

According to The Guardian’s respected music columnist Alex Petridis, it’s the content of the music itself that fires people up. “I think music is important: it deserves to be discussed and evaluated properly, and no one’s come up with a better way of doing it,” he wrote. “The rise of the internet may mean there’s no such thing as a definitive album review anymore, but that doesn’t matter… the more people discussing and evaluating, the better.”

While music journalism can be biased, disposable or (at worst) sink into self-indulgent waffle, as a genre it’s served as a fertile breeding ground for spawning incisive, informed writers, many of whom have gone on to write books which have not only changed the way we hear music but have helped us make sense of popular music’s importance in the wider cultural milieu.

As with rock history itself, though, there are myths about music-writing that still need to be debunked. For example, while it’s generally accepted that 20th-century rock journalism only got into its stride after the breakthrough of The Beatles, forward-thinking, intellectually slanted music-writing arguably has its roots in 19th-century classical-music criticism. Indeed, some highly rated writers, such as The Times’ James William Davison and French Romantic composer Hector Berlioz (who doubled as a freelance critic for the Parisian press), wielded influence on the page as early as the 1840s.

Yet the game changed forever, for both critics and consumers, after Thomas Edison invented the phonograph (later trademarked as the gramophone in 1887). After early 10” and 12” discs started to appear at the dawn of the 20th Century, the idea of the burgeoning music fan absorbing recorded music at home began to become a reality.

Yet the game changed forever, for both critics and consumers, after Thomas Edison invented the phonograph (later trademarked as the gramophone in 1887). After early 10” and 12” discs started to appear at the dawn of the 20th Century, the idea of the burgeoning music fan absorbing recorded music at home began to become a reality.

Though America’s Billboard magazine was founded as early as 1894 – initially building its reputation by covering circuses, fairs and burlesque shows – modern music criticism found itself a more tangible foothold when Whisky Galore author and co-founder of the Scottish Nationalist Party, Compton Mackenzie, founded Gramophone magazine in 1923. Though still devoted to classical music, this pragmatic monthly quickly embraced the idea of reviewing records, simply because a profusion of titles were starting to be released, and it made sense for reviewers to give guidance and make recommendations for the consumer.

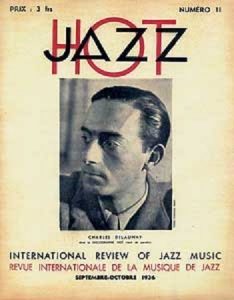

Twentieth-century music writing, however, found its feet properly while jazz rose to prominence during the 1930s. In France, the Quintette Du Hot Club De France were busily pioneering a continental blend of gypsy jazz, and two of the collective’s associates, critic Hugues Panassie and promoter Charles Delaunay, duly founded Jazz Hot, which encouraged scholarly jazz criticism prior to and after World War II. In the States, meanwhile, the long-running Down Beat was founded in Chicago in 1935, just as swing jazz was about to make stars of names such as Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Glenn Miller.

Twentieth-century music writing, however, found its feet properly while jazz rose to prominence during the 1930s. In France, the Quintette Du Hot Club De France were busily pioneering a continental blend of gypsy jazz, and two of the collective’s associates, critic Hugues Panassie and promoter Charles Delaunay, duly founded Jazz Hot, which encouraged scholarly jazz criticism prior to and after World War II. In the States, meanwhile, the long-running Down Beat was founded in Chicago in 1935, just as swing jazz was about to make stars of names such as Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Glenn Miller.

In New York, in 1939, Berliner Alfred Lion founded arguably jazz’s most influential imprint, Blue Note, and its pioneering 75-year history is vividly recalled throughout Richard Havers’ Uncompromising Expression, which was issued in 2014 with a 5CD companion box set. Iconic jazz trumpeter and bandleader Miles Davis recorded for Blue Note during his hard bop period of the early-to-mid-50s, and he’s the subject of another transcendent jazz-related book, the aptly titled The Definitive Biography, written by Ian Carr, the late Scottish jazz musician and also co-author of the essential genre compendium, The Rough Guide To Jazz.

During the post-war years, Billboard reporter and staff writer Jerry Wexler first used the term “rhythm and blues” in 1948. Adopted primarily to replace the contentious term “race music”, which had previously been attributed to music which came from the black community, “rhythm and blues” became a widespread term after Billboard printed its first Hot Rhythm & Blues Singles chart in June 1949.

During the post-war years, Billboard reporter and staff writer Jerry Wexler first used the term “rhythm and blues” in 1948. Adopted primarily to replace the contentious term “race music”, which had previously been attributed to music which came from the black community, “rhythm and blues” became a widespread term after Billboard printed its first Hot Rhythm & Blues Singles chart in June 1949.

Coining the term, however, was merely the tip of the iceberg for Wexler. His highly accessible Rhythm & Blues: A Life In American Music (co-written with Aretha Franklin/BB King biographer David Ritz) is an in-depth account of an astonishing 60-year career which included him landing a partnership with Atlantic Records and producing acclaimed albums such as Dusty Springfield’s Dusty In Memphis and Bob Dylan’s controversial “born again” LP Slow Train Coming.

In England, the then recently established New Musical Express followed Billboard’s lead, publishing the first UK Singles Chart (topped by Al Martino’s ‘Here In My Heart’) on 14 November 1952. However, while the 50s may have been a revolutionary decade during which the first officially recognised rock’n’roll stars such as Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis first climbed to prominence, contemporary music-writing remained relatively marginalised. Yet, it’s still possible to unearth examples of progressive music-writing from the late 50s and early 60s, such as one astonishing book by British architectural historian Paul Oliver. First published in 1965, Conversation With The Blues was meticulously researched and compiled from transcriptions of interviews the author conducted with pioneering musicians such as Roosevelt Sykes, Lightnin’ Hopkins and Otis Spann during a time when the American south was still racially segregated.

In England, the then recently established New Musical Express followed Billboard’s lead, publishing the first UK Singles Chart (topped by Al Martino’s ‘Here In My Heart’) on 14 November 1952. However, while the 50s may have been a revolutionary decade during which the first officially recognised rock’n’roll stars such as Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis first climbed to prominence, contemporary music-writing remained relatively marginalised. Yet, it’s still possible to unearth examples of progressive music-writing from the late 50s and early 60s, such as one astonishing book by British architectural historian Paul Oliver. First published in 1965, Conversation With The Blues was meticulously researched and compiled from transcriptions of interviews the author conducted with pioneering musicians such as Roosevelt Sykes, Lightnin’ Hopkins and Otis Spann during a time when the American south was still racially segregated.

Oliver came out of a school of writing that was behind the innovative, and still unsurpassed, Jazz Book Club. It was founded in 1956, with the first book for the imprint, written by musicologist Alan Lomax and entitled Mister Jelly Roll. During its decade-long existence it published books on both jazz and blues (back then people saw little difference in the two genres), including Louis Armstrong’s biography, Satchmo, and the brilliant Negro Music In White America, by LeRoi Jones… it’s a must-read.

By today’s enlightened standards, much of the coverage afforded pop artists in the early 60s now seems positively archaic. Such as it was, music criticism was largely restricted to gossip columns and staid news articles, though events such as The Beatles receiving their MBEs, tracking their various run-ins with celebrities, or reports of their “bad boy” rivals The Rolling Stones publically urinating on a petrol-station wall in March 1965 provoked tabloid-esque hysteria.

By today’s enlightened standards, much of the coverage afforded pop artists in the early 60s now seems positively archaic. Such as it was, music criticism was largely restricted to gossip columns and staid news articles, though events such as The Beatles receiving their MBEs, tracking their various run-ins with celebrities, or reports of their “bad boy” rivals The Rolling Stones publically urinating on a petrol-station wall in March 1965 provoked tabloid-esque hysteria.

Controversy and salacious details have, of course, always sold books as well as newspapers, so while Amazonian rainforests have since been sacrificed in the retelling of both these legendary bands’ histories, perhaps it’s no surprise that two of the most resonant books about The Beatles and the Stones relate to their respective managers. The urbane, enigmatic and intensely private Brian Epstein is the subject of one-time Melody Maker editor-in-chief Ray Coleman’s poignant but gripping The Man Who Made The Beatles, while the sights, sounds and smells of pre-“swinging” London are all richly recalled in erstwhile Rolling Stones svengali Andrew Loog Oldham’s memoir Stoned.

One or two music critics dropped hints that they harboured greater literary aspirations during the Merseybeat boom and the subsequent British Invasion. William Mann’s pioneering review of The Beatles’ Royal Command performance, for example, appeared in British broadsheet The Times in December 1963, and it used language (including descriptive metaphors such as “pandiatonic clusters” and “flat submediant key switches”) which suggested the writer thought of the music in terms of high art with a lasting significance, rather than merely disposable pop.

Mann’s instincts were sound, as popular music rapidly took off in terms of compositional sophistication and cultural influence over the next few years. By 1965, visionary artists such as The Beatles and Bob Dylan were releasing staggering records the likes of Rubber Soul and Bringing It All Back Home, which travelled light years beyond what had previously passed as “pop”. As the title of Jon Savage’s acclaimed 1966: The Year The Decade Exploded suggests, the following 12 months were a watershed year for the worlds of pop, fashion, pop art and radical politics, arguably defining what we now refer to as simply “the 60s”.

Mann’s instincts were sound, as popular music rapidly took off in terms of compositional sophistication and cultural influence over the next few years. By 1965, visionary artists such as The Beatles and Bob Dylan were releasing staggering records the likes of Rubber Soul and Bringing It All Back Home, which travelled light years beyond what had previously passed as “pop”. As the title of Jon Savage’s acclaimed 1966: The Year The Decade Exploded suggests, the following 12 months were a watershed year for the worlds of pop, fashion, pop art and radical politics, arguably defining what we now refer to as simply “the 60s”.

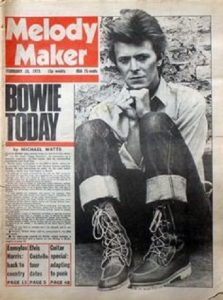

Ably assisted by the irresistible rise of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones – who both frequently graced their front covers – the New Musical Express and Melody Maker (which had originally been founded 1926 as a magazine for dance-band musicians) saw a significant rise in their sales across 1964-65. However, the golden age of modern rock music-writing was also arguably ushered in during 1966, when the initial issue of America’s first serious music magazine, Crawdaddy!, was published in New York that same February.

Ably assisted by the irresistible rise of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones – who both frequently graced their front covers – the New Musical Express and Melody Maker (which had originally been founded 1926 as a magazine for dance-band musicians) saw a significant rise in their sales across 1964-65. However, the golden age of modern rock music-writing was also arguably ushered in during 1966, when the initial issue of America’s first serious music magazine, Crawdaddy!, was published in New York that same February.

Crawdaddy!’s founder, a Swarthmore College freshman named Paul Williams, envisaged his new magazine as a publication where “young people could share with each other the powerful, life-changing experiences we were having listening to new music in the mid-60s”. The critics have since repeatedly praised Williams’ vision, with The New York Times later describing Crawdaddy! as “the first magazine to take rock and roll seriously”; Williams’ landmark magazine soon became the training ground for many well-known rock writers such as Jon Landau, Richard Meltzer and future Blue Öyster Cult/The Clash producer Sandy Pearlman.

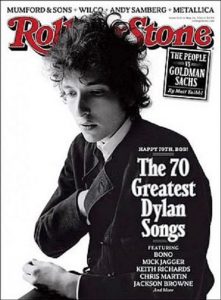

In the wake of Crawdaddy!, two new publications emerged which have since become synonymous with the history of rock’n’roll in America. Announcing its arrival in November 1967 with a lead article on the Monterey Pop Festival, Rolling Stone is still arguably the daddy of all American rock’n’roll magazines, while, late in 1969, Detroit record-store owner Barry Kramer founded popular monthly CREEM, which reputedly first coined the term “punk rock” in a May 1971 article about Question Mark & The Mysterians.

In the wake of Crawdaddy!, two new publications emerged which have since become synonymous with the history of rock’n’roll in America. Announcing its arrival in November 1967 with a lead article on the Monterey Pop Festival, Rolling Stone is still arguably the daddy of all American rock’n’roll magazines, while, late in 1969, Detroit record-store owner Barry Kramer founded popular monthly CREEM, which reputedly first coined the term “punk rock” in a May 1971 article about Question Mark & The Mysterians.

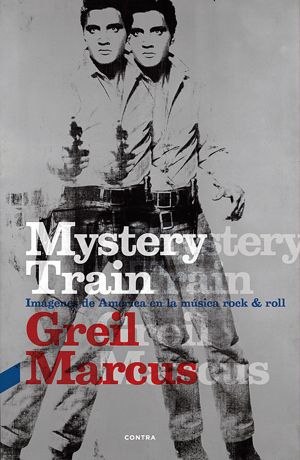

Between them, Crawdaddy!, Rolling Stone and CREEM mentored some of the most influential writers of the past 50 years. Arguably the most respected American cultural critic of them all, San Franciscan-born Greil Marcus, was Rolling Stone’s first reviews editor, and his scholarly style and literary approach is instantly recognisable. Dubbed “perhaps the finest book ever written about pop music” by New York Times critic Alan Light, Marcus’ most resonant tome arguably remains his 1975 opus Mystery Train: a remarkable book wherein he focuses intently on the careers of six legendary artists (Elvis Presley, Sly Stone, Robert Johnson, The Band, Randy Newman and Harmonica Frank) while simultaneously exploring the impact of rock’n’roll in the wider context of American culture.

Between them, Crawdaddy!, Rolling Stone and CREEM mentored some of the most influential writers of the past 50 years. Arguably the most respected American cultural critic of them all, San Franciscan-born Greil Marcus, was Rolling Stone’s first reviews editor, and his scholarly style and literary approach is instantly recognisable. Dubbed “perhaps the finest book ever written about pop music” by New York Times critic Alan Light, Marcus’ most resonant tome arguably remains his 1975 opus Mystery Train: a remarkable book wherein he focuses intently on the careers of six legendary artists (Elvis Presley, Sly Stone, Robert Johnson, The Band, Randy Newman and Harmonica Frank) while simultaneously exploring the impact of rock’n’roll in the wider context of American culture.

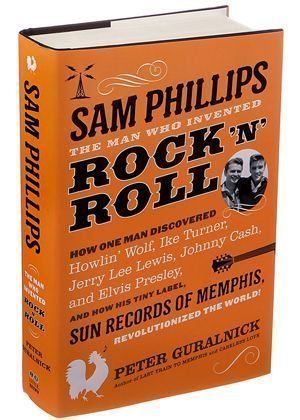

Another Rolling Stone and New York Times contributor-turned-literary giant is Peter Guralnick, who has long been regarded as one of the foremost authorities on rock, blues and country music in America. Some of his insightful early articles on trailblazing blues artists such as Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters were collected in his first book, Feel Like Going Home (1971), but perhaps his most lasting contribution to the genre is his masterful and impeccably researched two-volume Elvis Presley biography, Last Train To Memphis (1994) and Careless Love (1999), which place The King’s story in a rise-and-fall arc encompassing over 1,300 pages in all. Guralnick’s latest book, published in 2015, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock’n’Roll, is another masterpiece of scholarly research and vibrant writing.

Marcus and Guralnick are both renowned for their erudite styles, and their approach immediately influenced some of their contemporaries who have also produced essential biographies long on meticulous detail. First published in 1987, long-standing CREEM contributor Dave Marsh’s perennial Glory Days, for example, documents the minutiae of Bruce Springsteen’s career arc during the 80s, and includes in-depth critical interpretations of his revered albums Nebraska and Born In The USA.

Marcus and Guralnick are both renowned for their erudite styles, and their approach immediately influenced some of their contemporaries who have also produced essential biographies long on meticulous detail. First published in 1987, long-standing CREEM contributor Dave Marsh’s perennial Glory Days, for example, documents the minutiae of Bruce Springsteen’s career arc during the 80s, and includes in-depth critical interpretations of his revered albums Nebraska and Born In The USA.

Other writers who made their names during this period, however, preferred to go for the sensationalist jugular. Though eminently readable on its own terms, former Rolling Stone contributor Stephen Davis’ infamous unauthorized Led Zeppelin biography, Hammer Of The Gods, was later described by Chicago Tribune reviewer Greg Kot as “one of the most notorious rock biographies ever written”, and all three of the band’s surviving members have since poured scorn on its contents. But while there are undeniably superior volumes about legendary rock’n’roll hellraisers, such as Nick Tosches’ breathtaking Jerry Lee Lewis biography, Hellfire, and ex-Jamming! magazine editor/TV presenter Tony Fletcher’s fine Keith Moon portrait, Dear Boy, as exposés of vicarious, eyeball-popping rock’n’roll excess go, Hammer Of The Gods has arguably remained the yardstick, and has been reprinted several times.

Other writers who made their names during this period, however, preferred to go for the sensationalist jugular. Though eminently readable on its own terms, former Rolling Stone contributor Stephen Davis’ infamous unauthorized Led Zeppelin biography, Hammer Of The Gods, was later described by Chicago Tribune reviewer Greg Kot as “one of the most notorious rock biographies ever written”, and all three of the band’s surviving members have since poured scorn on its contents. But while there are undeniably superior volumes about legendary rock’n’roll hellraisers, such as Nick Tosches’ breathtaking Jerry Lee Lewis biography, Hellfire, and ex-Jamming! magazine editor/TV presenter Tony Fletcher’s fine Keith Moon portrait, Dear Boy, as exposés of vicarious, eyeball-popping rock’n’roll excess go, Hammer Of The Gods has arguably remained the yardstick, and has been reprinted several times.

Rock music-writing was very much in its ascendency in America in the late 60s, but during the 70s the UK rock press entered a golden age of its own. The NME, Melody Maker, Disc And Music Echo and Record Mirror had all enjoyed a spike in popularity during the late 60s, and, after Sounds was first published, in October 1970, British rock fans had five weeklies to choose from, before Disc ceased publication in 1972. In addition, the highly regarded monthly ZigZag (first published in April ’69) soon built a reputation for its thorough interviews, its diligently researched articles and initial editor Pete Frame’s groundbreaking, genealogical-style ‘Rock Family Trees’, which traced the events and personnel changes of artists ranging from The Byrds to John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. Frame’s first collection of Rock Family Trees was duly published in 1979, with a second volume following in 1983, and the two later appearing in a single book, The Complete Rock Family Trees, in 1993; since then there have been three other books in the series that, like their predecessors, are both beautiful to look at and fascinating to peruse.

During the late 60s and early 70s, Melody Maker and/or NME contributors such as Richard Williams, Michael Watts and Chris Welch were among the first music journalists to bring credibility to rock writing in Britain as the paper sought to cover prevalent styles such as glam and progressive rock. The coming of punk and new wave, however, brought about a sea change. Younger, snottier British writers, including Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons, were influenced by both the political climate of the time and radical contemporary critics such as CREEM/Rolling Stone contributor Lester Bangs (who peppered his restless invective with references to literature and philosophy as well as popular culture), while other rising stars, among them Jon Savage, Paul Morley, Mary Harron and Chris Bohn, brought an artier, more impressionistic edge to their coverage of the post-punk scene the late 70s and early 80s.

During the late 60s and early 70s, Melody Maker and/or NME contributors such as Richard Williams, Michael Watts and Chris Welch were among the first music journalists to bring credibility to rock writing in Britain as the paper sought to cover prevalent styles such as glam and progressive rock. The coming of punk and new wave, however, brought about a sea change. Younger, snottier British writers, including Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons, were influenced by both the political climate of the time and radical contemporary critics such as CREEM/Rolling Stone contributor Lester Bangs (who peppered his restless invective with references to literature and philosophy as well as popular culture), while other rising stars, among them Jon Savage, Paul Morley, Mary Harron and Chris Bohn, brought an artier, more impressionistic edge to their coverage of the post-punk scene the late 70s and early 80s.

Savage and Morley, especially, have become highly respected cultural commentators, and the former’s lauded England’s Dreaming has frequently been heralded as arguably the definitive history of Sex Pistols and the wider punk phenomenon.

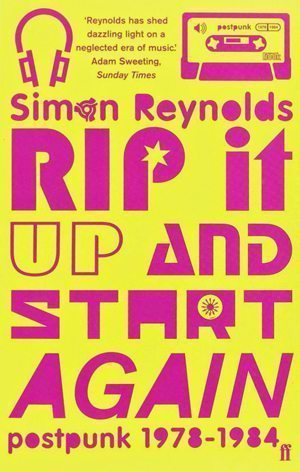

Several other highly individualistic writers to emerge from the British music press have gone on to pen essential tomes chasing any one of the myriad musical styles that erupted in the wake of punk. With Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King, NME and The Guardian freelancer Lloyd Bradley weighed in with the first major – and thus far unsurpassed – account of the Jamaican music’s history from ska to rocksteady, dub to the 70s roots’n’culture sound, while former Melody Maker staffer Simon Reynolds (whose own highbrow style was often distinguished by his use of Critical Theory and elements of philosophy) crafted Rip It Up And Start Again: Post-Punk 1978-84: an enthralling critique of how the era’s innovatory leading lights, such as PiL, Joy Division and Talking Heads, twisted punk’s original three-chord template into futuristic shapes which continue to transmogrify to this day.

Several other highly individualistic writers to emerge from the British music press have gone on to pen essential tomes chasing any one of the myriad musical styles that erupted in the wake of punk. With Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King, NME and The Guardian freelancer Lloyd Bradley weighed in with the first major – and thus far unsurpassed – account of the Jamaican music’s history from ska to rocksteady, dub to the 70s roots’n’culture sound, while former Melody Maker staffer Simon Reynolds (whose own highbrow style was often distinguished by his use of Critical Theory and elements of philosophy) crafted Rip It Up And Start Again: Post-Punk 1978-84: an enthralling critique of how the era’s innovatory leading lights, such as PiL, Joy Division and Talking Heads, twisted punk’s original three-chord template into futuristic shapes which continue to transmogrify to this day.

Arguably the most influential of the NME’s cover-mounted cassette giveaways during the 80s was C86, celebrating the eclectic nature of the UK’s indie scene in (you guessed it) 1986. One of that influential artefact’s collators was NME contributor and all-round indie champion Neil Taylor, so it’s fitting he would later author Document & Eyewitness: A History Of Rough Trade, which engages on two levels. Firstly, it’s an informal biography of the influential UK label/record shop’s unlikely founder, the softly spoken, almost monkish Geoff Travis, but it’s also a painstaking history of his shop(s), label and distribution company, which has sponsored singular talents such as The Smiths, The Strokes and The Libertines since its inception in 1978.

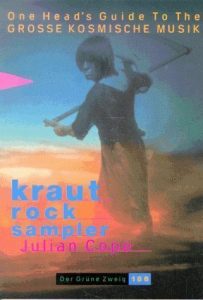

One of punk/post-punk’s chief tenets was its DIY spirit, so perhaps it’s inevitable some of the period’s maverick performers later mastered the challenge of writing words on music and successfully retained their credibility. The enigmatic German experimentalists of the early-to-mid-70s provided Julian Cope’s teenage bedroom soundtrack, and he returns the compliment in his highly acclaimed (and sadly long out of print) Krautrocksampler: a highly subjective and unflinchingly enthusiastic account of the rock’n’roll culture of post-World War II West Germany, focusing on singular talents such as Tangerine Dream, Faust and Neu!

One of punk/post-punk’s chief tenets was its DIY spirit, so perhaps it’s inevitable some of the period’s maverick performers later mastered the challenge of writing words on music and successfully retained their credibility. The enigmatic German experimentalists of the early-to-mid-70s provided Julian Cope’s teenage bedroom soundtrack, and he returns the compliment in his highly acclaimed (and sadly long out of print) Krautrocksampler: a highly subjective and unflinchingly enthusiastic account of the rock’n’roll culture of post-World War II West Germany, focusing on singular talents such as Tangerine Dream, Faust and Neu!

As with Julian Cope (and, indeed, some of the most enduring rock writers), Peter Hook never received any formal journalistic training, but he’s an able raconteur and, as bassist with two seismic post-punk outfits, Joy Division and New Order, he has more than a few tales to tell. He admirably reveals all in the no-holds-barred The Haçienda: How Not To Run A Club: a hair-raising account of how the titular Mancunian super club owned by New Order and Factory Records became the Madchester scene’s mecca during the late 80s, but then disintegrated in a hailstorm of gangs, guns, drugs and corruption.

In the 90s, the way music fans consumed their criticism began to change. Both Sounds and Record Mirror ceased publication in 1991, and glossier titles such as Select, Mojo and the primarily metal-oriented Kerrang! (which first appeared as a Sounds supplement in 1981) made greater inroads into the UK market, albeit temporarily.

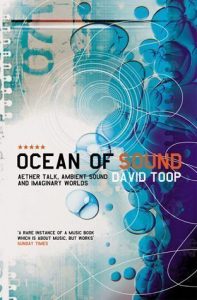

Yet while the medium was attempting to adjust, there was still a high turnover of genres for writers to focus upon as trends continued to mutate and pop’s eventful pre-Y2K years inspired a further clutch of resonant new books. Sounds/Mojo contributor David Cavanagh’s exhaustive The Story Of Creation Records revealed how the volatile Alan McGee rose from the breadline to take tea at No.10 Downing Street during the height of Britpop; David Toop’s Ocean Of Sound: Aether Talk, Ambient Sound And Imaginary Worlds traced the evolution of ambient music from Debussy through to Jimi Hendrix with anthropological precision, and Michael Moynihan and Dirk Søderlind’s Lords Of Chaos delved deep into the sinister history of the black metal scene.

Yet while the medium was attempting to adjust, there was still a high turnover of genres for writers to focus upon as trends continued to mutate and pop’s eventful pre-Y2K years inspired a further clutch of resonant new books. Sounds/Mojo contributor David Cavanagh’s exhaustive The Story Of Creation Records revealed how the volatile Alan McGee rose from the breadline to take tea at No.10 Downing Street during the height of Britpop; David Toop’s Ocean Of Sound: Aether Talk, Ambient Sound And Imaginary Worlds traced the evolution of ambient music from Debussy through to Jimi Hendrix with anthropological precision, and Michael Moynihan and Dirk Søderlind’s Lords Of Chaos delved deep into the sinister history of the black metal scene.

With the internet becoming a global reality on the cusp of the new millennium, many writers may have harboured concerns about the shape their collective future would take. Yet, while rock music weeklies are now largely a thing of the past, and online music bloggers have arguably become the norm, broadsheet coverage and the reassuring presence of established monthlies, including Rolling Stone, Mojo and Uncut, shows that print media is still very much a part of the fabric.

From the voracious reader’s point of view there’s since been a glut of quality to please their shelves (or download to Kindles), and it’s encouraging to think that some of the most authoritative words on music have been published since the dawn of the 21st Century.

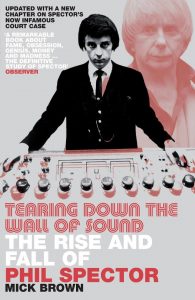

Books such as Tearing Down The Walls Of Heartache, Mick Brown’s thorough account of mercurial, edge-dwelling genius Phil Spector; Robert Hilburn’s peerless Johnny Cash: The Life and Starman, Paul Trynka’s consummate portrayal of David Bowie’s colossal, chameleonic career, all compete with the cream of classic rock biographies from the 20th Century, while Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History Of The Hip-Hop Generation and Richard Balls’ Be Stiff: The Stiff Records Story are timely reminders that well-executed compendiums about innovative genres and industry mavericks will always find an audience, no matter how formats evolve.

Books such as Tearing Down The Walls Of Heartache, Mick Brown’s thorough account of mercurial, edge-dwelling genius Phil Spector; Robert Hilburn’s peerless Johnny Cash: The Life and Starman, Paul Trynka’s consummate portrayal of David Bowie’s colossal, chameleonic career, all compete with the cream of classic rock biographies from the 20th Century, while Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History Of The Hip-Hop Generation and Richard Balls’ Be Stiff: The Stiff Records Story are timely reminders that well-executed compendiums about innovative genres and industry mavericks will always find an audience, no matter how formats evolve.

From Guns N’ Roses to The Jam, Public Enemy to Sonic Youth, many musicians have celebrated – and targeted – rock writers in song.

Listen to our exclusively curated Words On Music playlist here.