A Change Is Gonna Come: How Gospel Gave Birth To Soul

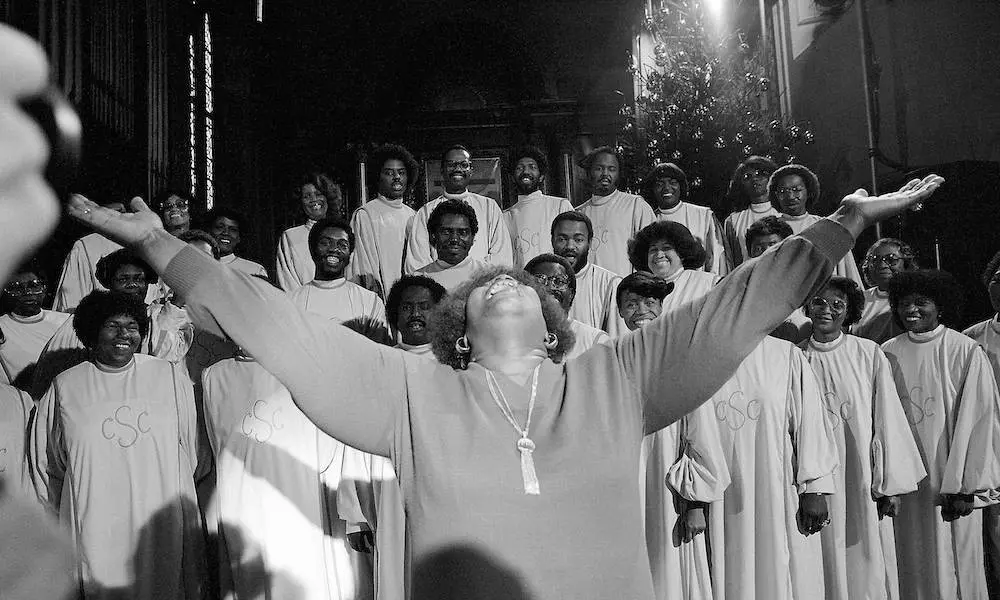

Gospel music has always had a major influence on R&B, with many of the biggest soul singers having started their vocal careers in gospel church choirs.

Two hundred thousand fans came to pay their respects to Sam Cooke at a memorial service in Chicago after his death, shot at the age of 33 by a frightened night manager in a cheap motel after an argument over a girl got out of hand. The entertainer’s death shocked the worlds of gospel, rhythm’n’blues, and pop.

Soul singers Lou Rawls and Bobby “Blue” Bland sang at his funeral in Los Angeles. Gospel singer Bessie Griffin was also due to sing but was too grief-stricken to perform; Ray Charles stepped up in her place and sang an apparently breathtaking “Angels Keep Watching Over Me.” It was appropriate that soul and gospel artists should honor Cooke’s passing, as he was the first – and biggest – gospel star to cross over into secular music. If any single person could be credited with defining soul music, then it would be Cooke.

‘Sam Cooke was the best singer who ever lived’

The exact events of his death have been disputed ever since, but one thing that unites everyone who was touched by Cooke’s music is a certain knowledge that his was a unique talent. As Atlantic Records producer Jerry Wexler put it: “Sam Cooke was the best singer who ever lived, no contest. When I listen to him, I still can’t believe the things he did.”

Born in Clarksdale, Mississippi, in 1931, the young Sam Cook (with no “e”) was raised in Chicago, after his father became a minister in the Church Of Christ Holiness. Before he reached double figures, Sam was already singing in a gospel group – The Singing Children. As a teenager, he joined the Highway QCs gospel group, with whom he would appear on the supporting bill of all the big-name gospel acts that passed through Chicago. It was while singing with the QCs that he came to the attention of JW Alexander, singer, and manager of The Pilgrim Travelers, who, alongside The Soul Stirrers and The Five Blind Boys Of Alabama, were one of the “big three” in the competitive world of gospel quartet singing.

Gospel music is born

Also called Southern gospel, due to the vastly predominant area of the United States where it was popular, the first thing to understand about the gospel quartet style is that the groups weren’t quartets. The name comes from the four-part harmonies they used – tenor, lead, baritone, and bass. The origins of the style are lost in the mists of time, but it probably began to evolve in the late 19th Century. Certainly, by the early decades of the 20th Century, gospel quartet singing was a big deal.

The Stamps Quartet had a hit with “Give The World A Smile” in 1927, and groups such as The Five Blind Boys of Alabama, who came out of the Alabama Institute For The Negro Blind in Talladega, and The Dixie Hummingbirds from Greenville, South Carolina, were popular even before World War II broke out. Over the next few decades, groups such as The Zion Harmonizers, from New Orleans, The Golden Gate Quartet, hailing from Norfolk, Virginia, and Nashville’s Fairfield Four, cemented the style, traveling the South in buses, raising the roofs of churches and auditoriums throughout the chitlin’ circuit in gospel battles that pitched one group against another in a show of one-upmanship that left audiences in tatters.

Gospel music took many elements from preaching and brought them to the stage. As Peter Doggett explains in Electric Shock: 125 Years of Pop Music, “Inherent to the black gospel tradition is the trading of lines between preacher and congregation, the call-and-response, a regimented structure which is the living likeness of spontaneity.” Many artists had also begun incorporating elements from blues and jazz into gospel music – despite this being a clear violation of religious territory towards “the devil’s music”.

Georgia Tom turned from secular music such as “It’s Tight Like That” to gospel after his wife had died in childbirth, in response to which he wrote the gospel classic “Precious Lord, Take My Hand” under his real name of Thomas A Dorsey. Having, as Greil Marcus put it in Mystery Train, his groundbreaking 1975 exploration of the sound of America, “Scandalized pious black families throughout the South with his suggestive lyrics… he became the ‘father of modern gospel’ by combining blues and jazz modes with sanctified themes. Drawing on the spiritual “We Shall Walk Through The Valley In Peace,” Dorsey composed “Peace In The Valley” while riding on a train in 1939, thinking about the war that had just begun in Europe, measuring his fears against the suddenly comforting valley he found himself passing through.”

A change is gonna come: Sam Cooke And The Soul Stirrers

One of the most influential and popular jubilee quartet groups was The Soul Stirrers. Originally from Trinity, Texas, their innovative use of twin lead singers allowed them to deliver an interplay that could work their audience into a frenzy greater than most of their rivals, mirroring the ecstasy of the Baptist church. Back with the Highway QCs, Sam Cooke had made a lasting impression on JW Alexander – so much so that when The Soul Stirrers’ lead singer, Rebert Harris, decided that the loose morals that went with life on the road was too great a burden for his conscience, Sam was recruited as his replacement. He was just 20 years old.

Harris’ were big shoes to fill. As the gospel historian Tony Heilbut notes in The Gospel Sound, Harris had redefined quartet singing: “Lyrically, he introduced the technique of ad-libbing… Melodically, he introduced the chanting background repetition of key words. As for rhythm, ‘I was the first to sing delayed time. I’d be singing half the time the group sang, not quite out of meter,’ but enough to create irresistible syncopations.” At first, Cooke struggled to fit in. “Sam started out as a bad imitator of Harris,” recalled fellow Soul Stirrer Jesse Farley. But soon Cooke found his own voice – and what a voice it would be. Controlled, without histrionics, Cooke sang with an effortlessness that had the listener hanging on every word.

Deeply soulful, yet velvet smooth, Cooke’s voice was perfectly suited to the narrative story-songs he was writing. He always maintained that the trick to songwriting was a simple melody that even children could sing. “Touch The Hem Of His Garment” is a perfect example of how the combination of Cooke’s songwriting and singing would make for mouth-watering music. He wrote the song on the way to a recording session with The Soul Stirrers, simply flicking though The Bible until he found a story he liked, one that was familiar to his audience. Already featuring his trademark yodel (“whoa-oho-oh-oh-oh”), “Touch The Hem Of His Garment” was one of his Cooke’s gospel recordings before turning to the so-called “devil’s” music’ in 1957, the first big gospel star to go secular.

Gospel music becomes soul music

As Peter Guralnick explains in Sweet Soul Music, Cooke’s decision shook the world of gospel to its very roots: “To appreciate the magnitude of the event, it is necessary to imagine Elvis Presley abdicating his throne, or The Beatles finding Jesus at the height of their popularity. For if the world of gospel was considerably smaller than that of either pop or rhythm and blues, its loyalties were all the fiercer, and the spectacle of the idolized singer of one of gospel’s most popular groups converting, however tentatively and innocuously, to ‘the devil’s music’ was enough to send shockwaves through the worlds of both gospel and pop.” A single, “Loveable,” was released under the not-too-hard-to-crack pseudonym of Dale Cook. It was followed in autumn 1957 by “You Send Me,” under Sam’s own moniker, and hit No.1 on both the rhythm’n’blues and pop charts. More hits followed – “Only Sixteen,” “Cupid,” “Chain Gang,” “Bring It On Home To Me,” “Shake,” and more; he notched 29 Top 40 hits on the pop chart alone.

A tough businessman, Cooke was among the first African-American artists to take control of his work, launching his own record label and publishing company. He lived the life of a superstar, but tragedy was never far away. His first wife died in a car crash, and his son Vincent drowned at home in the family pool.

After being turned away from a whites-only motel in Shreveport, Louisiana, and hearing Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ In The Wind,” Cooke wrote what many consider to be his greatest work, “A Change Is Gonna Come.” “I think my daddy will be proud,” he told Alexander after writing the song, which combined his increasing passion for supporting the Civil Rights movement with the questions raised by his religious background. In it he sings, “I don’t know what’s up there, beyond the sky,” and that “It’s been a long, a long time coming/But I know a change is gonna come/Oh yes it will.” He played the song to his protégé Bobby Womack, who said that it sounded deathly. Cooke agreed: “Man, that’s kind of how it sounds like to me. That’s why I’m never going to play it in public.” And he never did. Cooke died from that gunshot two weeks before the song’s release.

More than any other singer in history, Sam Cooke influenced an entire genre. Virtually every successful soul singer of the 60s followed in his footsteps; “A Change Is Gonna Come” became an anthem for the Civil Rights movement, and was covered by Cooke’s admirers. When Cooke’s old friend Aretha Franklin recorded it, she added her own introduction: “There’s an old friend that I once heard say something that touched my heart, and it began this way…” before launching into an extraordinary performance.

‘I want people to feel my soul’

And yet, Cooke wasn’t the first singer to apply his successes with gospel music to create crossover hits in what were initially termed the “race” charts. One of the most important pioneers was Ray Charles, who sang so sweetly at Cooke’s funeral. Charles had started out copying Nat King Cole, but soon found his own voice. And it was by reaching deep inside himself that he discovered what it was he could offer the world. As he explained in the early 50s, “I try to bring out my soul so that people can understand what I am. I want people to feel my soul.”

“Soul” was a term that had been bandied about more and more as a key element in Southern music, with it being claimed by both sides of the religious divide. Peter Doggett explains: “For Aretha Franklin, the daughter of a preacher man, ‘soul’ was how her father sang and declaimed from the pulpit. To Thomas Dorsey, ‘soul’ was an adjective that should be reserved for one form of music: African-American gospel singing. The soul was for Christ, the heart for politics and romance, so the secular brand should be known as ‘heart music’.”

For Ray Charles, the idea of soul music was simply being truthful to what lies deep within. In his autobiography, he explained his approach. “I became myself. I opened up the floodgates, let myself do things I hadn’t done before, created sounds which, people told me afterward, had never been created before… I started taking gospel lines and turning them into regular songs.” This sometimes blatant strategy (he changed “This Little Light Of Mine” into “This Little Girl Of Mine,” for example) could alienate even his own musicians, as one backing singer reportedly refused to sing such blasphemy and walked out. For Charles, he had hit upon a formula that, while revolutionary for many, seemed obvious to him. As he wrote in his autobiography, “I’d been singing spirituals since I was three, and I’d been hearing the blues for just as long. So what could be more natural than to combine them?”

Message songs

If Charles could trace his inspiration to the age of three, Solomon Burke could beat that comfortably. Burke says that his grandmother had seen his coming in a dream some 12 years before his birth. Such was the impact of her dream that she founded a church in anticipation of his coming – Solomon’s Temple: The House Of God For All People. Burke began preaching at the age of seven. Within a couple of years, he had built a reputation as the “Wonder Boy Preacher”, and, by 12, had taken his ministry on the radio and on the road. As a young man had hoped to take his group, The Gospel Cavaliers, to perform at a local talent competition, but when they failed to show, he sang solo, making such an impression that he was introduced to the owner of New York’s Apollo Records, who released his first record in 1955. However, Burke had no desire to stick with gospel music (though he retained his ministry, not to mention a sideline as an embalmer, until his death in 2010). He later signed for Atlantic, having huge crossover hits with “Cry To Me” and the gospel-infused “Everybody Needs Somebody To Love.”

And yet, things could go the other way just as easily. Mahalia Jackson, whose career had been overseen by Dorsey, found that she lost her black audience as she became an international star. Another gospel act who refused to cross over was Stax signees The Staple Singers, though they would incorporate pop songs into their act, and sing message songs rather than strictly sticking with Christian themes.

Like Sam Cooke, Mavis Staples grew up singing gospel in Chicago. The two singers lived close together, in fact, and Mavis recalled that, alongside many other future soul singers, Cooke used to visit the Staples’ home. “I grew up in Chicago. We lived on 33rd Street, and everybody lived on the 30s. Sam Cooke, Curtis Mayfield, Jerry Butler…

“When I was about nine years old I began singing with my family. Pops called us kids into the living room… and he began giving us voices to sing that he and his sisters and brothers would sing when they were in Mississippi.” Naturally, the songs they sang were spirituals. “Our very first song Pops taught us was ‘Will The Circle Be Unbroken’.” The Staple Singers began singing at churches and soon found themselves in demand. By the late 50s, they’d become popular recording artists, Mavis’ deep voice astonishing radio listeners. “The disc jockey would come on the radio and say this is little 13-year-old Mavis. People would say, ‘No that’s not a little girl, that’s got to be a man or a big fat woman, not a little girl.’”

The family group’s other unique selling point was Pops Staples’ guitar playing. Having grown up hearing Charley Patton and Howlin’ Wolf playing on Dockery Farm in Mississippi, he tried to copy their styles. “For years, we were singing gospel and didn’t know that Pops was playing the blues on his guitar,” Mavis revealed. This blues influence found its way into his daughter’s singing. Country legend Bonnie Rait described Mavis’ voice, saying: “There was just something so sensual about it without being salacious, and that’s the thing that really moved you so much, because normally you’d think that gritty, you know, roadhouse, kind of weathered voice is associated with the kind of sexuality of the blues music.” Despite sticking with religious themes, The Staple Singers were nonetheless crossing lines that, in the Deep South’s Bible Belt, should not be crossed.

From the altar to the stage… and back again

Like Staples, Aretha Franklin had much in common with Sam Cooke. Like him, her father was a preacher, and a hugely popular one at that. CL Franklin was known as the man with The Million Dollar Voice, and his popularity meant that their home was often full of famous faces, including Cooke’s. Aretha became infatuated by Sam, joining him on the road, and, despite her gospel background, chose to follow him by becoming a pop singer – with her father’s blessing. CL managed his daughter’s early career, which saw some success. But it wasn’t until 1967 that she truly broke through. After signing with Atlantic Records, she headed to Alabama, to work with the legendary Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section at FAME studios. The hits flowed – “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You),” “Respect,” “(You Make Me Feel Like A) Natural Woman,” “Chain Of Fools,” “I Say A Little Prayer”… The gospel influence allowed her to deliver rousing, personal, joyful music with a power and force that rammed the songs home.

Cooke’s influence was everywhere in the mid-60s. Soul music had become big business, and its biggest stars honored their idol. In Memphis, Otis Redding was enjoying huge success at Stax Records (who themselves had a gospel subsidiary called Chalice), and, when he wowed the rock crowd at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, he opened with Cooke’s “Shake.” This appearance would help bring soul music to a white audience in the United States, where music had traditionally been segregated (“rhythm’n’blues” was a term coined by Jerry Wexler, while working at Billboard magazine, as an alternative to the previous “race music” chart).

Alongside Otis Redding, soul singers including Joe Tex, Don Covay, Ben E King, and Arthur Conley were proud to be following in Cooke’s footsteps. But the influence of gospel music wasn’t confined to black artists. As a young boy, Elvis Presley would sit outside the black church in his hometown of Tupelo, Mississippi, and listen to the powerful sounds that emanated from within. He dreamed of being a gospel singer, and would continue to sing gospel both privately and publicly for his whole life. He scored a UK No.1 in 1965 with a moving version of The Orioles’ “Crying In The Chapel,” while one of his favorite songs was Tomas Dorsey’s “Peace In The Valley,” which he sang throughout his career. When he famously jammed in the so-called Million Dollar Quartet alongside Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis, gospel music made up a large chunk of their output. Cash and Lewis recorded gospel albums, as did other rock’n’rollers, including Little Richard (who famously ditched rock’n’roll mid-tour in 1957 to devote himself to the Lord’s mission).

And still Sam Cooke’s influence permeated the world of music. His close friend and singing partner Bobby Womack, who himself would enjoy a career spanning many decades, was enjoying success with his family group, The Valentinos. Their 1964 hit “It’s All Over Now” was covered by The Rolling Stones, giving the group their first UK No.1 hit. Even Bob Dylan’s first album included a gospel element, in the traditional “In My Time Of Dying” (sometimes known as “Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed”). The gospel influence in Dylan’s later work was brought out by a 1969 album by the Los Angeles-based The Brothers And Sisters, Dylan’s Gospel, in which a number of his songs, such as “I Shall Be Released,” were given a powerful gospel reading. (Dylan himself would make a series of Christian albums a decade later.)

More than six decades have passed since Cooke went secular, but the influence of the gospel music he loved remains. Current acts such as The Sounds Of Blackness, Take 6, and Kirk Franklin have enjoyed huge success with their interpretation of the genre – Franklin alone boasts 12 Grammy Awards, while Take 6’s 2016 album, Believe, was hailed as one of their finest yet.

What started out as a risk for Cooke, to leave the gospel world behind, has created something that long outlived his short life, and remains vital today. Those prophetic words from Cooke’s masterpiece seem to have come true for his music, if not for him:

There have been times that I thought I couldn’t last for long

But now I think I’m able to carry on

It’s been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change is gonna come, oh yes it will