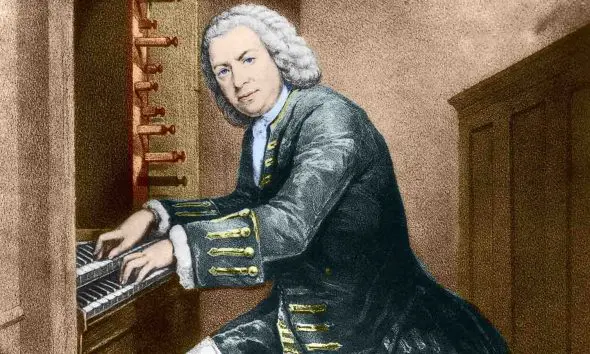

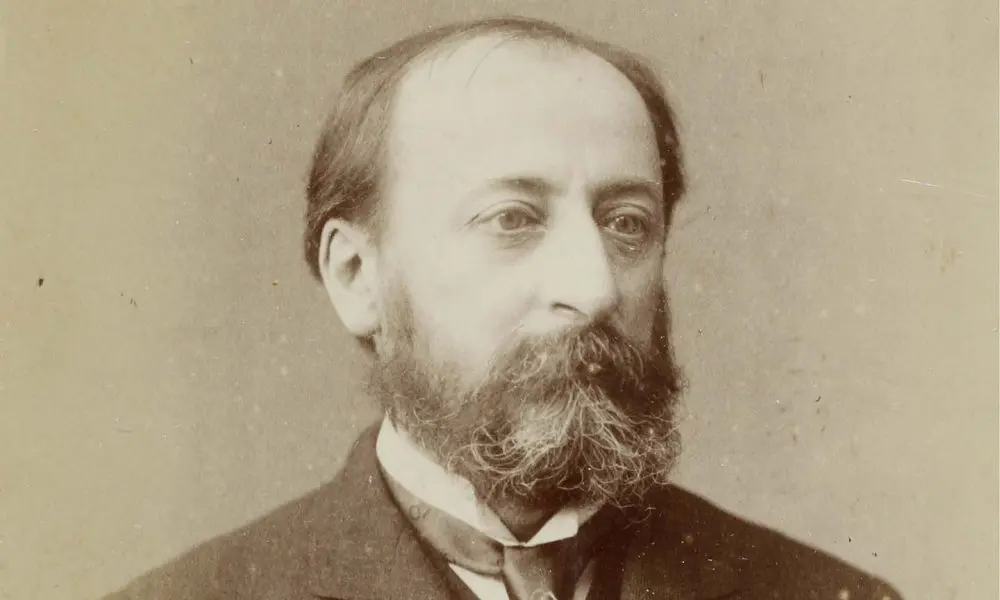

Camille Saint-Saëns: A Celebration Of The French Composer

Composer Camille Saint-Saëns died 100 years ago – to celebrate his legacy we take a look at his remarkable life and music.

Would the real Camille Saint-Saëns please stand up? Some composers wear their hearts and souls on their sleeve. This French 19th-century colossus (1835-1921) was not one of them – yet his music is no less impressive or lovable for that. It simply makes it extra complex to identify the real person behind the notes.

Saint-Saëns could not be described as neglected but arguably remains under-appreciated beyond his ubiquitous ‘Organ Symphony’ and the Carnival of the Animals, which he prevented from being published in his lifetime – suspecting, rightly, that it would become too popular for the good of his other music. Listen to The Kanneh-Masons’ recent recording for a fine demonstration of why.

Camille Saint-Saëns

Camille Saint-Saëns’s works encompass every genre from 13 operas, including Samson et Dalila, to piano études that have helped to form performers’ techniques for over a century. There is chamber music galore, notably two fabulous cello sonatas; two concertos for that instrument, five for piano and three for violin – though we only seem to hear No. 3 regularly; and a raft of symphonic poems plus further symphonies (try the enchanting No. 1).

Raised by his mother and great-aunt after his father’s early death, Saint-Saëns was desperately precocious, composing his first piece aged three. Despite a meteoric career as a child prodigy pianist – he once offered to play as an encore, from memory, any one of the 32 Beethoven sonatas – he quickly set his sights on becoming a composer.

He grew to be a true polymath, his spread of interests and expertise almost dizzying: mathematician, writer, zoologist, botanist and fossil hunter, he added astronomy to that list and once used the proceeds of some duos for harmonium and piano to commission a telescope to his own specifications. With this, he would examine the stars from his Parisian rooftop, sometimes joined by his pupils from the Ecole Niedermeyer where, in his twenties, he had his only teaching job. He became, too, a legendary organist, holding the chief post at the Madeleine for two decades from 1858.

Saint-Saëns wrote music “as an apple tree grows apples”

Throughout, Camille Saint-Saëns wrote music, as he put it, “as an apple tree grows apples”. Nevertheless, he was something of a compositional magpie, collecting influences and novel colours the way a chef collects spices: a bit of paprika from Spain for the Havanaise for violin and orchestra, graphically Middle Eastern flavours for the ‘Egyptian’ Piano Concerto No. 5 (written in Luxor) and even a discarded idea by his teenage star pupil, Gabriel Fauré, immortalised in Saint-Saëns’s popular Piano Concerto No. 2. His extensive travels took him to 27 countries, including two tours of the US in the early 1900s, as well as Russia and, even more astonishingly, Uruguay.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 found Camille Saint-Saëns heading for safety in London. Like many exiled Parisians, he loathed the smog, the weather and the food; but he found a sympathetic milieu thanks to his friend Pauline Viardot, the great opera singer and composer, who recreated her celebrated Parisian salon while living near Marylebone High Street. Her voice had been the inspiration behind Saint-Saëns’s opera Samson et Dalila – though, to his regret, she never sang it. It was probably via contacts he made through her that he was much later commissioned by London’s Philharmonic Society (today the Royal Philharmonic Society) to write his ever-popular ‘Organ Symphony’. Although Covent Garden had refused to stage one of his operas, even when Queen Victoria personally pleaded with them to do so, Saint-Saëns did not share the popular view that the British were philistines: he believed “the English love and understand music, and …the contrary opinion is a mere prejudice”.

Saint-Saëns founded the Societé Nationale de Musique

Back in Paris after France’s ignominious defeat by Prussia, in 1871 Saint-Saëns joined forces with the singer Romain Bussine and a group of composers and writers, including Fauré, Henri Duparc, César Franck, Jules Massenet and many more, to found a new Societé Nationale de Musique. The idea was to promote French music and encourage its creation. Until then, it had been overshadowed by German composers and dominated, besides, by grand opera, leaving instrumental and chamber works under-represented and identifiably French character lacking in evidence. Shaking off German influence after the war was crucial to the society’s raison d’etre, and to Saint-Saëns himself.

As founder of the Société, Camille Saint-Saëns transformed the fortunes of French music for the next three decades. Fauré once recalled: “The truth is that before 1870 I would never have dreamt of composing a sonata or a quartet. At that period there was no chance of a composer getting a hearing with works like that. I was given the incentive when Saint-Saëns founded the Société Nationale de Musique in 1871 …” Bussine wrote that the Société was “the cradle and sanctuary” of French art: “Everything that was great in French music, from 1870 to 1900, came through it. Without the Société Nationale, most of the works that are the honour of our music not only would not have been performed, but perhaps would not even have been written.”

The Société’s task became harder still when Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle and Parsifal were unleashed on the world during the late 1870s and early 1880s, exerting a pull that Ernest Chausson, another member of the Societé, described as affecting him like a “red spectre”. Although in his youth Saint-Saëns had championed “progressive” composers, notably Liszt – and Liszt returned the favour – with advancing years he morphed into a hardline musical conservative, engendering plenty of grudges along the way and having no patience for the more iconoclastic younger composers such as Debussy and, later, Stravinsky – the premiere of whose Le Sacre du Printemps he witnessed in horror in 1913.

“Art is intended to create beauty and character”

But what of his own musical philosophy? “Art is intended to create beauty and character,” he wrote. “Feeling only comes afterwards and art can very well do without it. In fact, it is very much better off when it does.” All that fluidity, flamboyance and sparkle was in some ways a mask for a troubled man. As time went by, perhaps it became part of his escape from a horrific personal tragedy from which he never truly recovered.

Aged 40, Saint-Saëns married a much younger woman, Marie Truffot; they settled, together with Saint-Saëns’s mother, in a fourth-floor apartment, and soon had two infant sons. But in 1878, their two-year-old, André, fell out of a window and was instantly killed. Overcome with grief, Marie was unable to feed the six-month-old baby. They sent him to her mother for care, but he died soon afterwards. The devastated Saint-Saëns regrettably blamed his wife for the children’s deaths. Their marriage hung by a thread for three years, until, while they were on holiday, he went out one day – and never went back. He never saw Marie again. She attended his state funeral, heavily veiled.

Camille Saint-Saëns vanished for a second time not long after his mother’s death in 1888 – eventually turning up in Las Palmas, living under an assumed name. For the rest of his life, he travelled extensively, particularly in north Africa; and his wanderings helped to inspire such works as his Africa Fantasy and the Suite Algérienne. Some commentators consider that Saint-Saëns was gay, had tried to live a conventional family life, but found matters more congenial in north Africa; others point out that no written proof of his homosexuality has ever been convincingly demonstrated, and that travel offered him escape from the scene of painful memories. Moreover, he enjoyed solitude for his work and hot climates suited him best. Ultimately he died in Algiers, where he was spending the winter for the sake of his health.

“A most irritable man”

Saint-Saëns’s uncompromising personality made him plenty of enemies. Sir Thomas Beecham, who conducted the composer in his own piano concertos, described him as “a most irritable man”; and once he rebuffed a dinner invitation from a fan who begged, “But could you not be very nice, just for me?” by saying: “I don’t want to be nice to you.” There were other sides to him, though, notably great warmth and generosity towards those he genuinely liked and respected – especially Fauré, who became virtually a substitute son to him. It’s fair to say that Fauré owed Saint-Saëns his career, all the way from his first notes, penned as a schoolboy under Saint-Saëns’s tuition, to his appointment as director of the Paris Conservatoire.

Saint-Saëns’s last years, despite international adulation and the award of Grand Croix de Légion d’honneur, France’s highest official plaudit, found him as a solitary, embittered individual, his days brightened by his beloved poodle, Dalila. After his death, aged 86, his unique place among his contemporaries was described by the critic Henry Coles:

“In his desire to maintain ‘the perfect equilibrium’ we find the limitation of Saint-Saëns’s appeal to the ordinary musical mind. Saint-Saëns rarely, if ever, takes any risks; he never, to use the slang of the moment, ‘goes off the deep end’. All his greatest contemporaries did. Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and even Franck, were ready to sacrifice everything for the end each wanted to reach, to drown in the attempt to get there if necessary. Saint-Saëns, in preserving his equilibrium, allows his hearers to preserve theirs.”

These days, when equilibrium is in such short supply, perhaps Saint-Saëns’s music has truly found its time. We are lucky to have it.

Recommended recording – The Kanneh-Masons’ Carnival

The Kanneh-Masons’ album Carnival is a very special collaboration featuring all seven “extraordinarily talented” (Classic FM) Kanneh-Mason siblings, Academy Award-winning actor Olivia Colman, and children’s author Michael Morpurgo. Carnival includes new poems written by War Horse author Morpurgo to accompany Saint-Saëns’ humorous musical suite Carnival of the Animals. The poems are read by the author himself who is joined by The Favourite actor Colman.