Elgar’s ‘Violin Concerto’: The Mystery Behind The Masterpiece

Explore the intriguing musical mystery behind Edward Elgar’s ‘Violin Concerto’ – which to this day has never been wholly solved …..

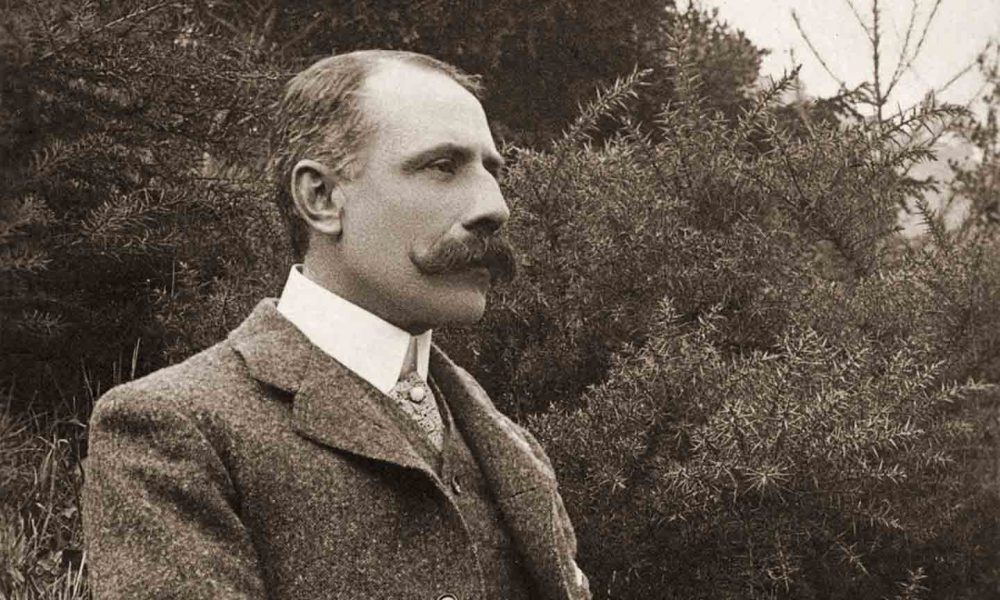

When the Royal Philharmonic Society commissioned a Violin Concerto from Edward Elgar in 1909, the composer was at the very height of his powers. He created in this remarkable work one of the longest and most emotionally complex violin concertos the world had yet seen. And at its heart, he implanted a mystery – which to this day has never been wholly solved.

Elgar had made his name with the Enigma Variations in 1899, in which he painted musical portraits of his friends. Ten years later, he wrote a mysterious inscription on the Violin Concerto’s manuscript, in Spanish. “Aqui está encerrada el alma de …..” “Herein is enshrined the soul of …..”

Whose soul does it enshrine? And why?

Listen to our recommended recording of Elgar’s Violin Concerto, performed by Nicola Benedetti, on Apple Music and Spotify.

Elgar’s Violin Concerto: The Mystery Behind The Masterpiece

The autumnal, introverted nature of Edward Elgar’s Violin Concerto adds to its sense of longing and uncertainty. While these qualities are typical of Elgar to some degree, the timing here is significant. The renowned violinist Fritz Kreisler gave its world premiere on 10 November 1910; by then, the triumphalism of the Victorian era was receding, and an unsettling wind of change was starting to be felt – one that led in 1914 into the global tragedy of World War I.

Elgar’s Violin Concerto seems an extraordinarily personal work. Gone is the upbeat grandeur of the Pomp and Circumstance Marches or the Symphony No. 1; instead, we sense ambiguity from the very beginning (for instance, it takes a while for the concerto’s tonality to become established). The raw tenderness of the second subject, the slow movement’s long-breathed, sighing phrases, and above all, the astonishing accompanied cadenza in the finale foreshadow the heartrending intimacy of Elgar’s ‘Indian summer’ creations after World War I – his three major chamber works and the Cello Concerto.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the violin was Elgar’s own instrument in his youth. It formed a crucial part of his daily bread as a self-taught jobbing musician, working his way up from a modest background – his father had a music shop in Worcester – as he strove for recognition as a composer. He did not achieve this in earnest until he was past 40.

The intriguing five dots in the concerto’s dedication

The five dots in the concerto’s dedication have received probably as much attention in themselves as the entire work, and various intriguing stories surrounding them have turned out (rather disappointingly) to be red herrings. The most likely candidate for the five dots, and the one for which there appears to be most evidence, is usually considered to be a female friend whom Elgar nicknamed “Windflower,” since she shared a first name – Alice – with his wife. Alice Elgar, nearly a decade her husband’s senior, does not appear to have been much perturbed by his series of friendships with or crushes upon younger women; there is even some evidence that she encouraged it, aware of the benefits for his creative energy. ‘Windflower’, was Alice Stuart-Wortley, daughter of the painter John Everett Millais and the wife of an MP.

Edward Elgar found the process of writing the Violin Concerto agonizing at times; throughout it all, Alice Stuart-Wortley was his confidante, egging him on when his energy was flagging. Elgar told her he was creating ‘Windflower’ themes for the piece – the gentle, questioning second subject of the first movement is prime among them. “I have been working hard at the Windflower themes, but all stands still until you come and approve!” he wrote to her.

Later, he told Alice, “I have no news except that I am appalled at the last movement and cannot get on: – it is growing so large – too large I fear, and I have headaches; Mr (William) Reed (leader of the London Symphony Orchestra) comes to us next Thursday to play it through and mark the bowings in the first movement, and we shall judge the finale and condemn it … I go on working and working and making it all as good as I can for the owner.”

One potential clue lies in the Enigma Variations

But “Alice” was not the only name with five letters… One potential clue to an alternative lies in the Enigma Variations themselves.

Each variation is a musical portrait: Edward Elgar’s wife, friends masculine and feminine, and, as grand finale, Elgar himself. The individual titles are fanciful nicknames, games of word association. ‘Nimrod,’ a mythical hunter, refers to August Jaeger, his editor at Novello. Jaeger means hunter in German; Nimrod is a hunter. And so forth.

But the penultimate variation – the unlucky 13th (and yes, Elgar was superstitious about it) is headed only by three dots. It’s a tender piece during which a rustle of side-drum mimics the sound of a steamer’s engine, while the clarinet quotes Mendelssohn’s Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage. This variation is now thought to be a tribute to Elgar’s first love, Helen Weaver, a young violinist to whom he had been engaged for several months. After her mother’s death, however, Helen broke off with him and emigrated to New Zealand – a move that entailed a long sea voyage. It is likely that health reasons determined this move and that she, like her mother, was suffering from tuberculosis. Elgar was left behind, heartbroken. As for the concerto, a strong case could exist for Helen – a violinist with a name five letters long – as the soul enshrined therein.

More complex solutions could exist

More complex solutions could exist, too. By the time Edward Elgar wrote the Violin Concerto, many of his friends of Enigma Variations fame were no longer alive. The Spanish quote, from the novel Gil Blas by Alain-René Lesage, is drawn from a passage in which a student reads an epitaph on a poet’s tomb. Elgar’s biographer Jerrold Northrop Moore suggests that behind each of the concerto’s movements lay both a living inspiration and a ghost: Alice Stuart-Wortley and Helen Weaver in the first movement, Elgar’s wife and his mother in the second, Billy Reed and the late Jaeger (‘Nimrod’), in the finale.

Still, Elgar had a penchant for puzzles and assuredly knew their worth in terms of publicity. When he placed that inscription on the Violin Concerto, he knew full well how intrigued his public would be. Research by Elgar’s biographer Michael Kennedy suggested that the original inscription was ‘El alma del’ – the extra ‘l’ implying a specifically feminine recipient. It seems the composer then changed this specifically to deepen the mystery. “The final ‘de’ leaves it indefinite as to…gender,” he wrote to a friend. “Now guess.”

We’ve been guessing ever since. And yet, who could escape the impression, from this most elegiac of violin concertos, that the soul enshrined therein is that of its composer: E-L-G-A-R…

Recommended recording

Our recommended recording of Elgar’s Violin Concerto is performed by Nicola Benedetti with the London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Vladimir Jurowski. Geoff Brown at The Times noted, “She takes on an epic and makes magic”, and The Guardian’s music critic Erica Jeal observed, “Benedetti’s tone and decisiveness is made for this work, and she brings an understated edge to the added miniatures, too.”

Nicola Benedetti’s recording of Elgar’s Violin Concerto has been digitally released.