Best Piano Concertos: 15 Greatest Masterpieces

Explore our selection of the best piano concertos featuring masterpieces by composers including Beethoven, Chopin, Mozart and Rachmaninov.

Supposing you’re at a shoe shop and you have free rein to select the slinkiest, most stratospherically-heeled jobs on the rack, but what you actually need is a good pair of hiking trainers… Oh, and can you bring yourself to leave the purple suede slingbacks behind? This is rather like trying to choose the top ten best piano concertos from a repertoire so rich that it could keep us happy listening to nothing else for the rest of the year. I’ve therefore picked 15, but some ace favorites are still missing, and I am horrified to find that the list is all-male. My one rule is to include only one concerto by each composer, but this does, naturally, give you the chance to explore the competition from their other works too. And I have broken the rule in any case… Scroll down to explore our selection of the greatest piano concertos.

15: Messiaen: Turangalila

It’s not called a concerto, but Olivier Messiaen’s gargantuan ten-movement symphony to love, sex, God, and the universe features a solo piano part that could defeat any concerto on home turf. It was premiered in Boston in 1949, conducted by Leonard Bernstein, and was written for the French pianist Yvonne Loriod, whom Messiaen later married. Turangalîla combines eclectic influences, including Indian spirituality, Indonesian gamelan, and a synaesthetic fusion of color with sound; and the composer tops the lot with an ondes martenot, the electronic swoops of which made it a favorite in the scores of horror movies. Yvonne’s sister Jeanne Loriod was this instrument’s chief exponent. Love it or loathe it, Turangalîla remains a one-off experience.

14: Busoni: Piano Concerto

Weighing in at 70 minutes and featuring a male chorus in the final movement – one of a mere handful of piano concertos that incorporates such an element – Ferruccio Busoni’s concerto, written between 1901 and 1904, can lay claim to being one of the biggest in the repertoire. That extends to the orchestration, which includes triple woodwind and a large percussion section. Fortunately, it is not only quantity that it offers, but quality too – but given the sheer weight of demand placed on all concerned, performances of it are relatively rare.

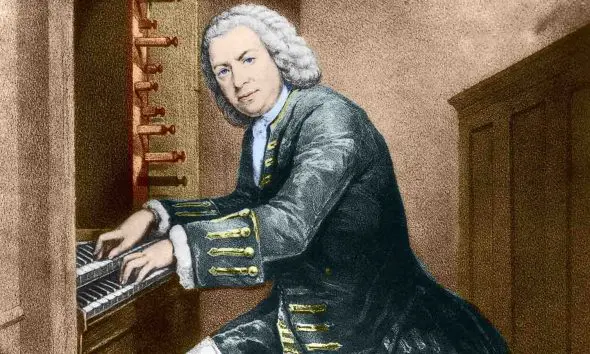

13: Bach: Keyboard Concerto In D Minor

This may be a controversial choice since Bach’s concertos are really for harpsichord. But that doesn’t mean they can’t also sound a million dollars on the modern piano, and in the 21st century, there is scant reason to confine them to quarters. There is a healthy number of them, all breathtakingly beautiful; among them, the D minor concerto edges ahead for its brilliant, toccata-like writing, its ebullient rhythms, and its poised, meditative slow movement.

12: Saint-Saëns: Piano Concerto No. 2

Nobody twinkles in quite the same way as Camille Saint-Saëns. His Piano Concerto No.2, one of the greatest piano concertos, was written (like Grieg’s) in 1868 and was once described as a progression “from Bach to Offenbach.” It opens, sure enough, with a solo piano cadenza that is not many miles away from the style of a baroque organ improvisation. This leads into a stormy opening movement, for which Saint-Saëns filched a theme by his star pupil, the young Gabriel Fauré, who had set aside the choral work for which he had written it and did not seem to mind when his teacher turned it into a smash hit. Next comes a debonair scherzo and an irrepressible tarantella finale.

11: Ligeti: Piano Concerto

Written in the 1980s, György Ligeti’s Piano Concerto is a true contemporary classic. In five movements, it is by turns playful, profound, and startling, often all three at once. Among its generous complement of percussion are castanets, siren whistle, flexatone, tomtoms, bongos, and many more; its musical techniques are every bit as lavish and include, for instance, the use of three time signatures at once. As dazzlingly original as the composer’s astonishing Etudes for solo piano, with which it shares some vital qualities, it deserves to be part of every adventurous soloist’s repertoire.

10: Grieg: Piano Concerto

Grieg’s sole Piano Concerto (1868), one of the greatest piano concertos, made its publisher, Edition Peters, such a healthy profit that they gave its composer a holiday flat in their Leipzig premises. The concerto’s wide appeal is evident from the first note to the last: the dramatic opening drum-roll and solo plunge across the keyboard, the lavish melodies with their roots in Norwegian folk music… Moreover, this concerto presented a structure that was copied by Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, and Prokofiev, to name but three, the one that came almost to define our notion of the “war-horse” piano concerto. An attention-grabbing opening; a big tune in the finale that rises to ultimate prominence; you found them here in Bergen first.

9: Bartók: Piano Concerto No. 3

Bela Bartók’s last piano concerto was written for his wife, Ditta Pásztory-Bartók, intended as her birthday present in 1945. The composer was seriously ill with leukemia and it killed him before he could complete the work; his friend Tibor Serly was tasked with orchestrating the final 17 bars. The concerto is collegial, serene, lively, even Mozartian in its sense of proportion and balance. It betrays no hint of the composer’s troubled exit from wartime Hungary and the struggles of his life in exile in the US.

8: Ravel: Piano Concerto In G Major

Here the jazz age comes to Paris with iridescent orchestration, split-second timing, and the occasional crack of a whip. Writing in 1929-31, Ravel was still relishing his recent trip to New York, during which his friend George Gershwin had taken him to the jazz clubs in Harlem; the impact is palpable. “Jazz is a very rich and vital source of inspiration for modern composers, and I am astonished that so few Americans are influenced by it,” Ravel said. The remarkable harmonic colors of the slow movement are a result of “bitonality” – music written in two different keys at the same time. Nevertheless, don’t miss Ravel’s other concerto, for left hand only, which was written for Paul Wittgenstein, who had lost his right arm in World War I.

7: Chopin: Piano Concerto No.1

The lyricism, delicacy, and balance required in Chopin’s two concertos can show a pianist at his or her finest; as in Mozart, there is nowhere to hide, and any deficiency in touch or control from the soloist is instantly shown up. Nevertheless, this music is not just about pianistic proficiency: it’s hard to find any other romantic concertos that contain such utterly genuine, guileless, enchanting, youthful poetry (Chopin was barely 20 at the time). Listen out for the piano’s duet with the saxophone-like bassoon in the slow movement.

6: Schumann: Piano Concerto

Premiered in 1845, with Clara Schumann at the piano and Felix Mendelssohn conducting, this was the only one of Robert Schumann’s attempts at a piano concerto that made it to final, full-sized form. Its intimacy, tenderness, and ceaselessly imaginative ebb and flow open a window into the composer’s psyche and especially his devotion to Clara, whom he had married in 1840. The final movement’s tricky rhythms are clearly inspired by those of Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto; the two works require a similar lightness, attack, clarity, and exuberance.

5: Prokofiev: Piano Concerto No. 2

Although some of Prokofiev’s other piano concertos are more often performed, the Piano Concerto No. 2, one of the greatest piano concertos, is the most personal and, in emotional terms, has the most to say. This rugged, rocky, devastating piece is the work of a young and precocious composer and pianist (he was about 22) faced with a terrible tragedy: one of his closest friends, Maximilian Schmidthof, took his own life in 1913. Prokofiev had already started work on the piece, but its trajectory was transformed. As if that was not bad enough, the manuscript was then destroyed in a fire following the Russian Revolution of 1917, and Prokofiev had to reconstruct it. Finally, the premiere took place in 1924 in Paris, with the composer as its soloist.

4: Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 1

This concerto took two different forms – symphony, then two-piano sonata – before settling down as a concerto. It was profoundly affected by the fate of Robert Schumann. Only months after he and Clara had extended their friendship to the young genius from Hamburg, Schumann suffered a devastating breakdown, attempted suicide, and was thereafter incarcerated in a mental asylum for the rest of his days, dying there in 1856. The D minor concerto’s slow movement has been shown to evoke the words “Benedictus qui venit in nomine domini”, suggesting that the work, completed in 1858, is Brahms’s personal Requiem for his mentor. Also, hear Brahms’s vast, great-hearted, and utterly different Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major.

3: Mozart: Piano Concerto In C Minor, K491

Mozart’s 27 piano concertos comprise the largest body of piano concertos that are regularly heard in concert halls, although (scandalously) a relatively small handful are regularly performed. Only two are in a minor key, and while the D minor K466 is the more popular, the C minor is my personal favorite for its wide emotional range, its ceaseless stream of inspiration, and its highly sophisticated writing not only for the piano but also the woodwind, which virtually become soloists in their own right, treated in the slow movement almost like an operatic ensemble.

2: Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No. 2

Come on, don’t be mean – this concerto is perfect. It’s almost impossible to fault one page, one phrase, one note in one of the greatest piano concertos. The snobby view of it as sentimental is unfortunate. Bad performances sometimes convey it that way, but frankly, they are wrong; if you hear Rachmaninov’s own recording, the piece comes over as cool and controlled, containing dignity, valor, passion, and poetry in equal measures. In this work, written in 1900-01, Rachmaninov came back to composition after a period of deep depression and creative block. A course of hypnotherapy with Dr. Nikolai Dahl had helped to restore him to the rails, and his genius flamed back in the proverbial blaze of glory. Hear his other concertos too, of course.

1: Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 – and No. 5 too

Composers have been trying to beat Beethoven for 200 years. Few succeed. Choosing the best of his five piano concertos is an unenviable task – and so I suggest both his Fourth and Fifth concertos as equal crowning glories of the repertoire.

There is something ineffable about Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 – an inward, questing, exploratory work that is simply unique. The slow movement, in which the piano meets the orchestra’s aggressive outbursts with tranquil reflection, has been likened – supposedly by Franz Liszt – to Orpheus taming the wild beasts. It was premiered in 1808 with Beethoven himself at the piano (and his pupil Carl Czerny reported that the great man’s performance included many more notes than he had written down).

Beethoven began composing his ‘Emperor’ Piano Concerto No. 5 in 1809, while Vienna was under invasion from Napoleon’s forces for the second time. The first public performance of the concerto, at the Leipzig Gewandhaus with Friedrich Schneider as soloist in November 1811, made a powerful impression and the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung reported, “It is without doubt one of the most original, imaginative and effective, but also one of the most difficult of all existing concertos.” Beethoven’s final piano concerto was not a regretful farewell from one whose legendary abilities at the instrument were foundering on the rocks of his deafness, but a surge of glory from a composer whose capacity for reinventing himself showed itself in every piece. “I shall seize fate by the throat,” he once wrote to his childhood friend Franz Wegeler. “It shall not wholly overcome me. Oh, how beautiful it is to live – to live a thousand times.” Perhaps to write joyfully despite his suffering was his ultimate means of defiance.

Look out for some exciting new recordings of the concertos coming later in Beethoven’s anniversary year of 2020.

Recommended Recording

Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto recorded by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini.

Three titans – pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini – unite in one of the greatest ever performances of Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto.

“Great playing by a great pianist.” – The Gramophone Classical Music Guide, 2010

Our recommended recording of Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto can be bought here.

Blaine Snow

March 27, 2020 at 6:43 pm

Excellent and sometimes surprising list. Thanks! Now I have some new ones to get to know such as the Ligeti, Saint Saens, Busoni, and Messiaen.

Yeng

August 20, 2020 at 11:54 pm

No Rachmaninoff’s 3rd? Come on!

And Moritz Moszkowski’s 2nd Piano Concerto should be there, too. One of the most extraordinary works during the Romantic era, this concerto works like magic!

Hannah

September 15, 2020 at 5:36 pm

This is a fantastic list!

George Ferreira

March 4, 2021 at 11:15 am

At number 10

Should be Tchaikovsky’s

Piano concerto number one

To leave it off shows a lack

Of common sense, just saying.

Thanks, does antone else agree?

Nick Gunning

October 27, 2021 at 10:58 pm

Lots of background noise from the likes of ligetti- no Tchaikovsky 1st or 2nd, no liszt no Rachmaninov’s 3! Glad the Busoni got a mention, but not Saint Saens’5th. Brahms 1st but not the second? Including Messaien and Prokofiev but not Scriabin? I don’t let my dislike of Mozart’s twitterings get in the way of recognising his talent though I draw the line at some of the rackety 20th century offerings which might be technically skilful. After much polishing by the likes of liszt, busoni etc, Bach’s concertos do well, though he may not have ever owned a piano, and thought it would never catch on.

hee

August 5, 2022 at 4:49 am

Quite different taste.

Beethoven Piano concerto #3, 2nd movement.

Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 23: II. Adagio

Hummel: Piano Concerto in A Major, WoO 24, S4: II. Romanza. Adagio

Chopin: Piano Concerto no.2 op.21 – II Larghetto

Konrad Fernandez

August 27, 2023 at 8:39 pm

Beethoven 5 and 4, then Brahms 1 and 2