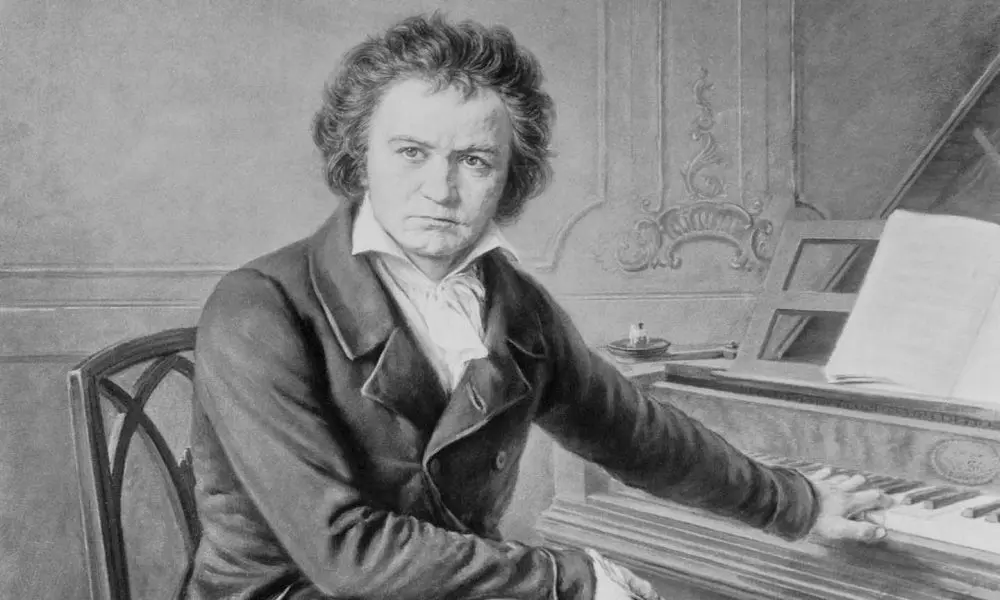

Beethoven’s Five (Or So) Piano Concertos

Our guide to Beethoven’s five piano concertos features Krystian Zimerman’s landmark recording with Sir Simon Rattle.

Beethoven’s five piano concertos trace a path from Classicism to Romanticism and are masterpieces of a genre he revolutionized. The first three show him as the young lion of Vienna, the fourth as the mature genius seeking to be worthy of his own gifts (of which he was well aware); and in No. 5 he let the scale of his imagination shine out, while someone else did the heavy lifting of actually playing the piano. The 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth provided the perfect reason for Krystian Zimerman to return to Beethoven’s piano concertos. “I had not played these pieces for a few years, and I miss them,” noted Krystian Zimerman. “Some concertos you can play all your life and still feel hungry for them. To these concertos, Beethoven belongs.” Scroll down to discover our guide to Beethoven’s piano concertos featuring Krystian Zimerman and Sir Simon Rattle’s landmark recording with the London Symphony Orchestra.

Explore our classical collection featuring limited edition vinyl and CDs.

Beethoven’s five (or so) piano concertos

Beethoven’s five piano concertos are all in three movements. Here their similarities end. The wonderful thing about Beethoven – OK, one of many wonderful things – is that he never repeats himself.

The earliest of Beethoven’s piano concertos that we generally hear, No. 2, was first drafted in the late 1780s and the last completed in 1809-10, by which time the world of Beethoven’s youth was being swept away by the Napoleonic wars. Technically, neither No. 1 nor No. 2 was really the first: Beethoven had written another piano concerto (Wo04) aged 14. If some of the dates around the big concertos seem a little bit vague, Beethoven usually wrote slowly and often worked on several different pieces simultaneously. Occasionally, though, he scribbled so fast that the ink scarcely had time to dry – and later, he would rewrite.

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1

The C major concerto, the official No. 1, was a case in point. Beethoven premiered it in 1795 in his first public concert in Vienna, having written the finale only two days earlier. His friend Franz Wegeler recalled him racing against the clock to finish it, handing over the sheets of manuscript page by fresh page to four copyists waiting outside. Nevertheless, he then revised it extensively; it was not finalized for another five years.

Unquenchable energy, wit, and good humor bounce out of this music. Its outer two movements are unmistakable for their vivacity; the first, moreover, presents the soloist with a choice of three cadenzas by the composer, the initial one modest in scale, the second more substantial, and the third – written much later – so long and demanding that some pianists avoid it for fear of overbalancing the whole piece. The ‘Largo’ is the longest of any in Beethoven’s concertos, which collectively offer some of his most sublime slow movements, seeming to make time stand still.

Click to load video

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 2

Of No. 2 in B flat major, Beethoven wrote self-deprecatingly to his publisher: “This concerto I only value at 10 ducats… I do not give it out as one of my best.” Yet if he hadn’t written anymore, we would still love him for this work. Genial, warm, sometimes ridiculously funny – try those off-beat loping rhythms in the finale – the B flat piano concerto seems to give us a glimpse of the young Beethoven who had dreamed of studying with Mozart (a longing thwarted by Beethoven’s mother’s death and his family issues thereafter). Beethoven uses the same concerto structure as Mozart: an opening allegro in processional mode, a lyrical slow movement, and a dancelike conclusion. Yet he pushes everything several steps further. He’s the ultimate musical disruptor. There’s nothing Mozartian about the idiosyncratic, folksy third movement or the fervent intensity of the exquisite central ‘Adagio’.

Click to load video

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3

If there’s a key in Beethoven associated with high drama, it is C minor: he used it for the Symphony No. 5, the ‘Pathétique’ Sonata, much later his last piano sonata, Op. 111, and the Piano Concerto No. 3. This was written as the 19th century was taking wing; its first performance, given by the composer himself, was on 5 April 1803. Only six months earlier, Beethoven had experienced a terrible crisis in which he faced up in earnest to his hearing loss. His Heiligenstadt Testament, the agonizing document intended as a will and addressed to his brothers, revealed that he had considered taking his own life but felt unable “to leave the world until I have brought forth all that is within me.”

His answer to that devastating episode was a decision to jettison his earlier methods and find a “new path.” Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 pushes the envelope further and deeper than he had formerly attempted in this genre: this is the darkest of emotional spheres, while the slow movement – in the ‘Eroica’ key of E flat major – travels to a deep, inward world where he, and we, find untold realms of peace.

Click to load video

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4

In the Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Beethoven inhabits new worlds that are both brave and breathtaking. It is brave, for a start, to begin a concerto with the soloist playing alone, very quietly. The piano’s initial phrase – a soft G major chord that pulses, then expands towards a questioning cadence – poses a challenge to the orchestra, which responds from faraway B major, adding to the impression that this music comes from a remote sphere with a touch of magic to it, unlike anything we have heard before. The mood is inward-looking, peculiarly visionary: a long way from the humor, dazzle, and storms of the earlier three works.

The slow movement again finds piano and orchestra in conversation: an aggressive, jagged idea is delivered in unison by the strings, then calmed by a hymnlike intonation from the soloist, who seems to adopt the role of prophet, orator or therapist (take your pick). At times the effect has been compared to the story of Orpheus calming wild animals with his music. The finale is a light-footed, somewhat elusive rondo, the piano’s lines much garlanded, the orchestra sympathetic, and the two working harmoniously together.

This concerto dates from 1805-6 and was first heard in a private performance at the palace of Beethoven’s patron, Prince Lobkowitz. Its public premiere took place on 22 December 1808 in a now legendary concert that Beethoven staged at the Theater an der Wien, which also included the premieres of the symphonies nos. 5 and 6 plus the Choral Fantasia – an evening so long, demanding, and freezing cold that much of the audience left before the end.

Click to load video

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5

The last concerto, subtitled the ‘Emperor’, is in Beethoven’s old favorite key of E flat major, and it lives up to its nickname in terms of grandeur, poise, and scale of conception. This is the only one of Beethoven’s piano concertos that the composer did not perform himself: by the time of its premiere in January 1811, his hearing loss was making that impossible. His patron and pupil Archduke Rudolph was its first soloist, again at Prince Lobkowitz’s palace – and he must have been pretty accomplished since Beethoven presents his pianist with a serious technical workout here.

The piece opens with a series of grand flourishes, effectively a cadenza punctuated with fanfare-like orchestral chords – another distinctly unconventional way to begin a concerto – before the main allegro gets underway. The slow movement is perhaps the most heavenly of them all, the piano dreaming against the background of hushed strings in the ethereal, distant key of B major. Finally, there arrives, via a hushed transition, a joyous and powerful celebration. While Wagner once referred to the Symphony No. 7 as an “apotheosis of the dance,” his description could equally well fit this overwhelmingly energetic finale.

Click to load video

Apparently, Beethoven considered writing a sixth piano concerto, but never completed it. It seems sad that he left the genre behind, perhaps because he could no longer perform these works himself. There could, however, be no more magnificent farewell than this. You could almost call it an ode to joy.

Recommended Recording

Krystian Zimerman and Sir Simon Rattle’s landmark recording of Beethoven’s Complete Piano Concertos with the London Symphony Orchestra was a major highlight of the celebrations to mark the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. Their outstanding performances, streamed on DG Stage from LSO St Luke’s and recorded live by Deutsche Grammophon in December 2020, were described as “history in the making” by The Times in their five-star review, which noted, “Zimerman is in terrific form and Rattle alert to every nuance in the pianist’s playing.”