Bach’s ‘St John Passion’: A Guide To The Sacred Masterpiece

Read our masterpiece guide to Bach’s ‘St John Passion’ and watch John Eliot Gardiner’s production on DG Stage on Good Friday, 2 April 2021.

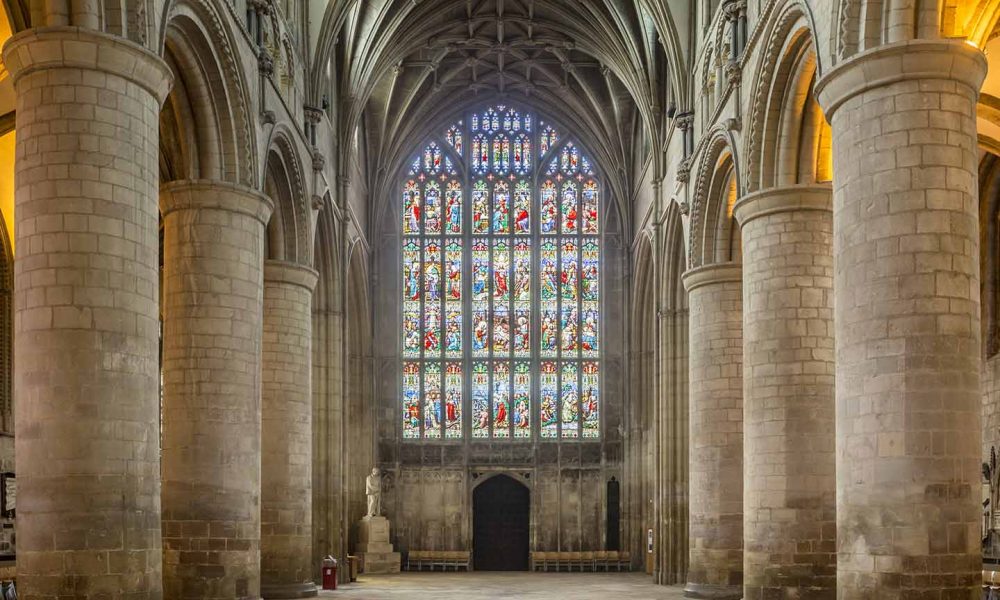

The St John Passion (Johannes-Passion in German), BWV 245, is a setting of the Passion story as related in St John’s Gospel. It was first performed on Good Friday, April 7, 1724, in Leipzig’s Nikolaikirche. Bach revised the work in 1725 and 1732 but it is heard most frequently today in the final version he completed in 1749 (though never performed during his lifetime).

Listen to John Eliot Gardiner’s Archiv recording of Bach’s St John Passion on Apple Music and Spotify and scroll down to read our guide to the sacred masterpiece.

Bach’s ‘St John Passion’: A Guide To The Sacred Masterpiece

For those new to the work – perhaps new to classical music – the term ‘passion’ may be perplexing when nowadays it is a word associated almost exclusively with strong emotions (as in ‘They fell passionately in love’ or ‘We have a passion for the food we produce’). In this instance, though, ‘passion’ has an alternative meaning, referring specifically to the story of the suffering and death of Jesus Christ. It comes from the Latin verb ‘patior’ meaning ‘to suffer, bear, endure’, from which we also get ‘patience’, ‘patient’, etc. Accounts of the Passion are found in the four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The first three of these (known as the synoptic gospels) all have similar versions of the story. The narrative of the Passion in the Gospel of St John varies considerably.

The Passion according to St John was heard on Good Friday

The Passion according to St Matthew was commonly heard as the Gospel for Palm Sunday, while St John’s version was heard on Good Friday. Until the Reformation, the text had been sung in Latin to plainchant or in a capella settings using plainsong, homophony, and polyphony. Over the next 150 years or so, this evolved into the concept of the oratorio Passion, a work that merged chorales, non-Biblical and devotional texts with gospel passages – and all sung in German.

The earliest known oratorio Passion to be performed in Leipzig was by Johann Kuhnau (a St Mark Passion) in 1721 – just two years before Bach succeeded to the prestigious title of Cantor at the Thomasschule. He was the third choice for the job – but it was one he retained for the rest of his life. His arduous duties involved playing the organ, teaching Latin and music in the Thomasschule, writing music for the church services of both the Nicolaikirche and Thomaskirche, and directing the music and training the musicians of two further churches. All this besides, famously, fathering twenty children (six of whom, sadly, did not survive into adulthood).

Bach composed some of the greatest spiritual music

The music that flowed from his pen during this period – and there was a significant amount – includes some of the greatest spiritual music ever written: the Mass in B minor, St Matthew Passion, Christmas Oratorio, nearly 300 church cantatas – and the St John Passion.

It has been said that of all Bach’s larger works, the compositional history of the St John Passion is by far the most complex. (By contrast, its later and more illustrious sister, the St Matthew Passion of 1727 was subject to very few and insignificant changes.) Lengthy articles and essays that make the head spin detail the many differences, sources, refinements, excision, and additions of the four versions of the St John Passion. Whereas the St Matthew Passion is an almost continuous succession of narrative – arioso – aria, giving the work a more contemplative and devout character, the St John Passion has a rag-bag of a text, drawing on Chapters 18 and19 of St John’s Gospel (in the translation of Martin Luther), two short interpolations from St Matthew’s Gospel, extracts from Psalm 8, chorale verses, and Passion poetry from Christian Weise, Heinrich Postel (whose texts for a St John Passion were also set by composers Christian Ritter and Johann Mattheson) and especially Barthold Heinrich Brockes. The latter’s libretto Der Für die Sünden der Welt Gemarterte und Sterbende Jesus (‘Jesus Tortured and Dying for the Sins of the World’) (1712) is also known as the Brockes Passion, among the earliest oratorio Passions. It was a free, poetic meditation on the story and was set to music by Telemann, Handel, and Mattheson among others.

For those curious to know the NBA (Neue Bach-Ausgabe) and BWV (Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis) numbers of every movement in all the various versions of the St John Passion, their running order, which voices sing what text, the text source, and the instruments, key and time signature for each section, click here.

A cosmic explanation for the phenomenon of Christ

So much for the material Bach used. What gives the work its distinct character and flavor is reflected in St John’s foremost intention: to provide a cosmic explanation for the phenomenon of Christ, concentrating on Christ as the eternal and omnipresent ruler rather than on his suffering. It is a theme that is established in the opening chorus. Bach seems to have thought of the chorale ‘Durch Dein Gefängnis’ as the central, pivotal point of the work: either side of this are the choruses ‘Wir Haben ein Gesetx’ and ‘Lässest du Diesen Los’ (which share the same music), while the aria ‘Es ist Vollbracht’ (‘It is fulfilled’), the climax of the narrative, is surrounded by the verses of the Passiontide chorale ‘Jesu Kreuz, Leiden und Pein’.

This symmetrical pacing is reflected in the running order of the Good Friday Vespers service itself, a simple liturgical structure that began and ended with a chorale, and placed the two parts of the Passion on either side of the sermon:

Hymn: Da Jesus an den Kreuze Stund

Passion: Part 1

Sermon

Passion: Part 2

Motet: Ecce Quomodo Moritur by Jacob Handl (1550-91)

Collect

Benediction

Hymn: Nun Danket all Gott

The five sections of the St John Passion are:

Part 1

1. Arrest (Nos. 1 -5), Kidron valley

2. Denial (Nos. 6 – 14), Palace of Caiaphas, the High Priest

Part 2

1. Court hearing with Pontius Pilate (Nos. 15 – 26)

2. Crucifixion and death (Nos. 27 – 37), Golgotha

3. Burial (Nos. 38 – 40), burial site

The narrator is the Evangelist (tenor). Jesus and all other male characters including Peter and Pilate are sung by a bass except the servant (tenor). Soldiers, priests, and populace are sung by a four-part chorus. Listen out for their contributions in such numbers as ‘Kreuzige!’ (the outcries to crucify Jesus), ‘Sei Gegruesset, Lieber Judenkoening’, and the fanaticism of the mob in ‘Waere Dieser Nicht ein Uebeltaeter’, described by Albert Schweitzer as “unsurpassably dreadful in its effect”. By contrast, the radiant music of the chorales was expected to be sung by the congregation.

“So transcendent in its divine benignity”

The Passion ends with the chorale ‘Ach, Herr, Lass Dein Lieb Engelein’. Here, says the American choral director and conductor Hugh Ross, “Bach is, as he alone knew how to be, the sublime comforter, the maker of music so transcendent in its divine benignity that there are no words with which to speak of it that would not seem impertinent.”

The German musicologist Christoph Wolff observes that, “Bach experimented with the St John Passion as he did with no other large-scale composition,” and concludes that, “as the work accompanied him right from his first year as Cantor of St Thomas’s to the penultimate year of his life, for that reason alone, how close it must have been to his heart”.

Listen to John Eliot Gardiner’s Archiv recording of Bach’s St John Passion on Apple Music and Spotify.

David ASHTON

April 14, 2022 at 2:54 pm

The entire Fourth Gospel which is a drama needs to be written as a classical opera

Stephen Rickert

June 6, 2023 at 11:52 pm

The final chorale of Bach’s “St. John’s Passion” is unspeakably beautiful. I sang it a boy soprano at the Washington Cathedral in the 1950s.