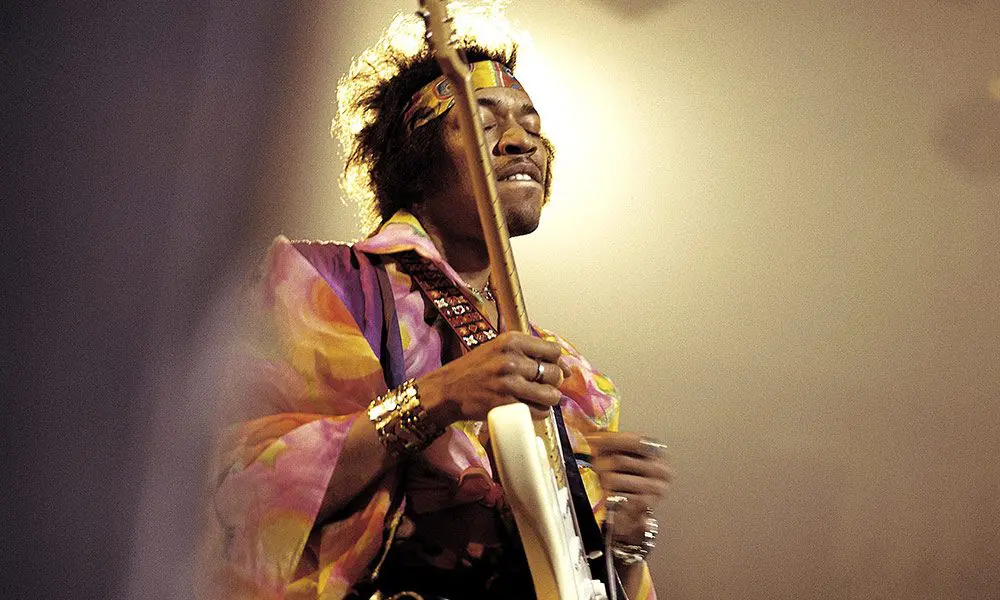

Jimi Hendrix

Jimi Hendrix is one of the most iconic guitarists in American popular culture known for classic songs like Purple Haze & The Wind Cries Mary.

Jimi Hendrix’s mainstream career may have lasted just four short years, yet he is widely hailed as one of the most influential guitarists ever to have graced the stage. Despite his premature death (aged just 27) in September 1970, he remains one of the most celebrated musicians of the 20th Century. The Rock and Roll Hall Of Fame is surely accurate in its assessment of Hendrix as “arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music”.

Highly respected US rock magazine Rolling Stone has ranked his three official studio LPs, Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland, in their Top 100 albums of all time, and Hendrix has been showered in posthumous awards. Yet while he is now cited as a peerless sonic innovator, one of rock’s great showmen – quite simply a genius – Hendrix initially came from the humblest of beginnings.

Though he was born of primarily African-American descent, Jimi’s paternal grandmother, Zenora ‘Nora’ Rose Moore was a full-blooded Cherokee from Georgia. She first met his paternal grandfather, Bertram Philander Ross Hendrix, on the road while the two of them were travelling around North America together as part of a Dixieland vaudeville troupe.

Jimi’s father, James Allen Ross ‘Al’ Hendrix, had just been drafted into the US Army to serve in World War II when he met Jimi’s mother, Lucille Jeter, at a dance in Seattle in 1942. The first of Lucille’s five children, Johnny Allen Hendrix was born on 27 November that same year, though in 1946 his parents officially changed his name to James Marshall Hendrix, the new Christian names honouring both Hendrix’s father and his late brother Leon Marshall.

The young Jimi’s home life was tough and frequently dysfunctional. Though his father was discharged from the army in 1945, the Hendrix family had little money and both Jimi’s parents struggled with alcohol-related problems. As a result, Jimi – a shy, gentle and retiring child – was often shuttled off to stay with his grandmother in Vancouver.

Jimi first fell in love with playing the guitar at school, though his father steadfastly refused to buy him one. He eventually found an old ukulele (with only one string) in some garbage in 1957 and mastered it by ear, playing along with early rock’n’roll hits, of which his favourite was Elvis Presley’s ‘Hound Dog’. Eventually, however, Jimi acquired his first real guitar in 1958 and seriously applied himself to it: playing along for several hours a day and learning tricks from records by pioneering blues guitarists such as Muddy Waters, BB King and Howlin’ Wolf.

By the time Hendrix graduated from Washington Junior High School, in 1958, his father had relented and bought him a red Silvertone Danelectro guitar. Despite this, Jimi was rootless and prone to trouble. Aged 19, he was twice caught by the authorities for riding in stolen cars and given the choice between going to prison or joining the US Army. Hendrix duly joined the 101st Airborne Division and was stationed at Fort Campbell in Kentucky. Though he met buddy (and future bassist) Billy Cox there, he hated the routine and the discipline and was eventually given an honourable discharge in June 1962.

Hendrix had begged his father to send his guitar to him while in the army; post-services, he paid his dues the hard way: initially moving to Clarksville with Cox and forming a band called The King Kasuals. Subsistence-level work followed, with Hendrix then spending the next two years playing what was known as the Chitlin’ Circuit (a series of US venues deemed safe for African-American musicians while America still struggled with racial segregation issues), where he earned his chops performing with pioneering soul, R&B and blues musicians, including Slim Harpo, Wilson Pickett and Sam Cooke.

Frustrated by the restrictions of being a sideman, Hendrix moved to New York City to try his luck, but, despite being taken in by Harlem-based girlfriend/mentor Lithofayne ‘Fayne’ Pridgeon, Hendrix again struggled to make ends meet and he again ended up touring and recording a series of early 45s, with highly respected acts such as The Isley Brothers, Little Richard, Curtis Knight and Joey Dee & The Starliters, across 1964-65.

By early 1966, Hendrix had learnt most of the tricks of his trade. He’d developed a flamboyant stage presence from playing the Chitlin’ Circuit with the R&B greats and he’d mastered most of the stage moves (such as playing the guitar with his teeth or behind his head) which he would later use to delight his fans. More presciently, he’d synthesised his own futuristic and highly original style of guitar playing, which fused Chicago blues, R&B and elements of rock, pop and jazz. Ready to go out on his own, he earned a residency at The Café Wha? in New York City’s Greenwich Village and formed his own band, Jimmy James & The Blue Flames, in the summer of 1966. It was here that he began working up some of the material he would shortly end up recording.

Though still virtually penniless, Hendrix became friends with Linda Keith – the then-girlfriend of Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards – who was knocked out by his musical abilities. An independent woman with means of her own, Keith initially recommended Hendrix to both the Stones’ manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, and Sire Records’ Seymour Stein, who both failed to see his potential. Another of her acquaintances, The Animals’ bassist Chas Chandler, however, was floored by one of Hendrix’s performances at The Café Wha? and wanted to sign him up there and then.

At the time he met Hendrix, Chandler was quitting The Animals and looking to manage and produce artists. Crucially, he also loved Hendrix’s version of Billy Roberts’ ‘Hey Joe’ (a rock standard also recorded by The Leaves, The Byrds, Love and more) and felt it could be a hit. To his eternal credit, Chandler saw Hendrix’s star quality from the off, and flew him back to England, where he was sure Hendrix would wow Swinging 60s-era London.

Chandler wasn’t wrong. He reputedly suggested that Hendrix drop his stage name, ‘Jimmy James’, and become the far more exotic-sounding ‘Jimi’ Hendrix before they’d even disembarked at Heathrow. He knew no time could be wasted in turning Hendrix into the star he clearly had the potential to be.

Hendrix hit the ground running in London. The pair left New York on 24 September 1966 and, within days, Hendrix had signed a management and production contract with Chandler and ex-Animals manager Michael Jeffery. On 30 September, Chandler took his still unknown new charge to see Cream perform at London Polytechnic. Hendrix met the band’s virtuosic lead guitarist, Eric Clapton, for the first time and asked if he could perform a couple of numbers. Clapton happily acquiesced and Hendrix ripped into a frantic version of Howlin’ Wolf’s ‘Killing Floor’. The band’s and the audience’s collective jaws dropped, with Clapton later admitting, in Keith Shadwick’s book Jimi Hendrix: Musician: “He played just about every style you could think of and not in a flashy way. I mean, he did a few of his tricks like playing with his teeth…but it wasn’t in an upstaging sense at all and that was it…he walked off and my life was never the same again.”

By 12 October 1966, Hendrix’s new band became a reality, with Chandler and Hendrix recruiting powerhouse ex-Georgie Fame drummer Mitch Mitchell and Afro-sporting bassist Noel Redding, of The Loving Kind. Though actually a guitarist first and foremost, the ambitious Redding learned quickly, taking to the bass like the proverbial duck to water. With their sonic ammunition duly primed, the newly christened Jimi Hendrix Experience thus got down to rehearsing and some serious gigging. They played a prestigious early run of shows supporting popular Parisian rock’n’roller Johnny Hallyday in France; slogged through countless one-night stands around provincial UK clubs; and played a run of crucial, reputation-establishing showcases in hip London niteries such as The Bag O’Nails, The Marquee, The Scotch Of St James and The Flamingo in Wardour Street.

Within months, Hendrix was the toast of London’s hip elite and could count members of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones among his friends. His quest for stardom was ably assisted when the Experience’s classic early 45s also charted highly in the UK. After crucial exposure on TV shows Top Of The Pops and Ready Steady Go!, the group’s atmospheric reading of ‘Hey Joe’ went to No.6 early in 1967, while March ’67’s ‘Purple Haze’ went straight to No.3. The record that introduced Hendrix’s highly original psychedelic rock sound, ‘Purple Haze’ had elements of the blues and brought in complex Eastern-style modalities, but it was also a strident rock anthem and arguably remains Hendrix’s most widely recognised song.

Hendrix’s popularity also surged after a famous stunt he pulled when – with help from some lighter fluid – he set fire to one of his beloved Fender Stratocasters at the end of the Experience’s set at London’s Astoria Theatre, one of the stops on a UK package tour with Cat Stevens, Engelbert Humperdinck and teen idols The Walker Brothers. The press coverage was widespread, though the Experience’s elegant third 45, ‘The Wind Cries Mary’ (a UK Top 10 hit in May 1967), showed that Hendrix’s music contained subtleties which didn’t always square with the image of the hard-rocking, volume-obsessed “Wild Man Of Borneo” as one less-enlightened British newspaper referred to him.

Signing to impresario Kit Lambert’s new Polydor-affiliated Track Records in the UK, and Reprise in the US, the Experience released two staggering LPs during 1967. Epochal May ’67 debut Are You Experienced reached No.2 on the UK charts (where it earned a gold disc) and later climbed to No.5 on the US Billboard chart, eventually enjoying multi-platinum sales Stateside. Raw, savage and irresistible, the album showcased Hendrix’s all-encompassing sonic spectrum, from strutting, cocksure rockers (‘Fire’, ‘Foxy Lady’) to slow, seductive blues (‘Red House’), R&B (‘Remember’) and stunning, psychedelic-tinged material such as the blissful title track (with its prominent, backwards-masked guitar and drums) and the complex but compelling ‘Third Stone From The Sun’, which hinted at the further greatness to come.

The Experience’s second LP, Axis: Bold As Love, was released in December 1967 and again charted prominently, rising to No.5 in the UK (receiving a silver disc) and No.3 in the US, where it earned a platinum certification. Critics often overlook Axis…, but it remains a magnificent record in its own right. Predominantly gentler and more reflective than Are You Experienced, it included the exquisite ballad ‘Little Wing’, the light, jazzy ‘Up From The Skies’ and the playful, Curtis Mayfield-esque soul-pop number ‘Wait Until Tomorrow’, as well as the sturdy rocker ‘Spanish Castle Magic’, which became a staple of Hendrix’s live set. Arguably its finest moments, however, were the acid-fried blues of ‘If Six Was 9’ and the astonishing titular song, which featured one of Hendrix’s most show-stopping guitar solos and innovative use of flanging (akin to that previously used on The Small Faces’ ‘Itchycoo Park’) on the song’s drum track.

By the end of 1967, Jimi Hendrix was a fully-fledged superstar in the UK, but in between making their initial two LPs, he had also begun to conquer his homeland. After nine months of non-stop graft establishing themselves as serious contenders in Britain, the Experience played at the world’s first major rock festival, Monterey Pop, on California’s Pacific Coast, in June 1967. The stellar bill also featured The Mamas & The Papas, Otis Redding and their Track Records labelmates The Who, but the Experience stole everyone’s thunder, playing one of their most dazzling sets, culminating with Hendrix again setting fire to his Stratocaster at the end of a truly incendiary version of The Troggs’ ‘Wild Thing’.

The Experience had blown minds on both sides of the Atlantic – and beyond in 1967 – and the band’s itinerary for 1968 included intensive touring in the US, where they decamped to make their third LP, Electric Ladyland, at New York’s expensive new state-of-the-art studio, The Record Plant. Continuing for much of the year, however, the protracted sessions stretched tensions to breaking point within the Experience camp. Prior to these sessions, Chas Chandler and Noel Redding, especially, had preferred to work quickly, recording songs after only a few takes. Hendrix, though, was on a Michaelangelo-esque quest for sonic perfection, and his band were frustrated by Jimi’s growing entourage and the number of people he was inviting to the sessions, some of whom (notably Traffic’s Steve Winwood and Jefferson Airplane bassist Jack Casady) ended up playing on some of the tracks. Such was the level of disruption that by the time the album was released, on 25 October 1968, Chas Chandler had quit as Hendrix’s co-manager (leaving Michael Jeffery in sole charge), and both Redding and Mitchell also temporarily split from the Experience.

For all the trials and tribulations, however, critics and fans alike agreed that Electric Ladyland was Hendrix’s unparalleled masterpiece. A record of staggering virtuosity, it featured everything from the monster heavy rock of ‘Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)’ to the New Orleans-style R&B of Earl King’s ‘Come On’, the urgent social commentary of ‘House Burning Down’ the aquatic jazz of ‘1983… (A Merman I Should Be)’ and even Noel Redding’s hooky, proto-Britpop number ‘Little Miss Strange’.

Commercial success aligned with the enthusiastic critical reception, sending Electric Ladyland to No.1 on the US Billboard Chart where it went double-platinum, while in the UK the LP also went gold and rose to No.6. It also spawned two Top 20 hits courtesy of Hendrix’s sublime version of Bob Dylan’s ‘All Along The Watchtower’ and the wah-wah and harpsichord-fuelled ‘The Burning Of The Midnight Lamp’, though this latter (confusingly) had already been released as a single prior to Axis: Bold As Love.

Mitchell and Redding rejoined the Experience for European and US tours during the first half of 1969, but the trio’s days were numbered. Redding had already formed a new band, Fat Mattress, and he quit after a show at the Denver Pop Festival in June 1969. Ironically, Hendrix’s most iconic live performance came shortly after the Experience split, when he played the massive Woodstock Music & Art Fair in upstate New York, in August 1969, with a pick-up band known as Gypsy Sun And Rainbows, featuring two percussionists, a returning Mitch Mitchell on drums and bassist Billy Cox. Hendrix eventually closed the event at around 8am on the final morning, and his set’s highlight, a stellar, feedback-riven solo rendition of the US national anthem, ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ (performed in protest against the Vietnam War), has been widely hailed as one his greatest live performances ever.

Post-Woodstock, Hendrix formed the short-lived Band Of Gypsys, with Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles, during the latter part of 1969. Featuring new funk- and blues-flavoured tracks and Hendrix’s aggressive, anti-war epic ‘Machine Gun’, their lone LP, Band Of Gypsys, was culled from two live shows held at New York’s Fillmore East on New Year’s Day 1970. Released by Capitol in June that same year, the LP went to No.6 in the UK and No.5 in the US (earning a double-platinum certification), but it proved to be the final LP released during Hendrix’s lifetime.

Hendrix’s manager, Michael Jeffery, had hoped the Experience would reform; when Hendrix toured North America in the spring and early summer of 1970, Mitch Mitchell was indeed back on the drums, though Billy Cox had permanently replaced Noel Redding. Consisting of 32 gigs, The Cry Of Love tour featured some of Hendrix’s biggest shows, including the massive Atlanta Pop Festival on 4 July, where the attendance was believed to have topped 500,000 people.

Hendrix worked intensively on songs for his fourth studio LP at his newly completed Electric Lady Studio complex, in New York, during the summer of 1970. He was close to completing what was reputed to be a new double-LP before touring commitments found him whisked back to Europe for the second leg of The Cry Of Love tour. Apparently jinxed from the off, the band played an equipment- and fatigue-blighted show at the Isle Of Wight Festival and then struggled through several difficult European dates, playing their final gig on 6 September on the German Isle Of Fehmarn, at a festival plagued by torrential rain and an aggressive Hells Angels biker chapter.

Tragically, Hendrix died just days later, on 18 September 1970. He had spent the night with a girlfriend, Monika Danneman, at her apartment at the Samarkand Hotel in London’s Notting Hill. While there has since been a lot of speculation about what may have caused his premature death, the coroner’s official (open) verdict remains death by asphyxia, seemingly caused by an excess of alcohol and barbiturates. What is certain, however, is that the day of Jimi Hendrix’s death was one of the saddest rock fans have ever had to endure.

Yet Hendrix lives on through his staggeringly innovative music, which continues to delight generations of new fans in the 21st Century. Beginning with a slew of early 70s LPs, such as Cry Of Love, Rainbow Bridge and War Heroes – all of which included material that could have ended up on his fourth album – Hendrix’s posthumous career has been notoriously convoluted. Since Al Hendrix won a protracted legal battle to gain control of his son’s songs and image rights in 1995, things have improved a little. After Al licensed the recordings to MCA through his family company, Experience Hendrix, 1997’s First Rays Of The New Rising Sun appeared, featuring remastered (and sometimes remixed) versions of songs previously available from The Cry Of Love and Rainbow Bridge, and it remains the closest anyone has so far come to presenting Hendrix’s last LP as the artist intended it to sound.

More recently, Experience Hendrix signed a new licensing arrangement with Sony’s Legacy Recordings, resulting in 2010’s Valleys Of Neptune, which featured unreleased material, including the much sought-after title track. While further releases may still be in the offing, long-term fans and newcomers alike are advised to snap up Universal Music’s two essential Hendrix DVD releases. The incendiary Live At Monterey in-concert film is an absolute must, while Jimi Hendrix: The Guitar Hero presents a fascinating double-disc documentary narrated by ex-Guns’ N’ Roses guitarist Slash, as well as a host of bonus features.

Tim Peacock