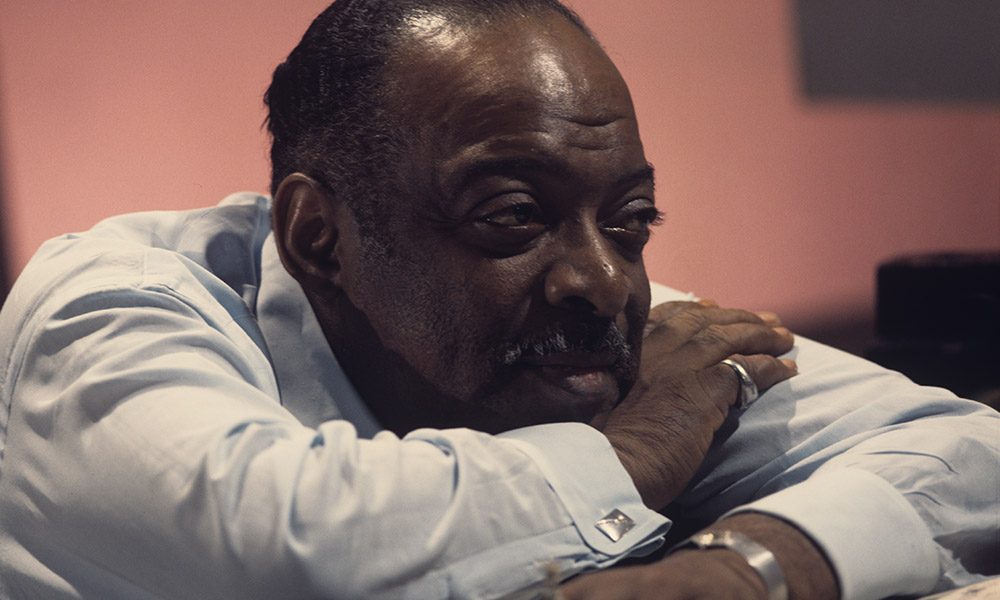

Count Basie

The Count Basie band always sounded so fresh: it was very much a jazz band but it played emotional music; at once simple, yet always stylish.

Along with Duke Ellington, Count was a leader in presenting big-band jazz. Whether it was back in the 1930s with limited recording technology to capture the sound of a band, or in the 1950s with the dawn of the hi-fi era, Basie’s bands always swung big and bold, yet Basie himself was a laconic soloist, inspiring, among others, Oscar Peterson. Most important of all, the Basie band always sounded so fresh: it was very much a jazz band but it played emotional music; at once simple, yet always stylish.

“I think the band can really swing when it swings easy when it can just play along like you are cutting butter.” – Count Basie

Born in Red Bank, New Jersey on 21 August 1904, Bill Basie took piano lessons at a young age, but his first thought was to become a drummer; fortunately, the piano won him over and he was soon studying the greats: Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith, James P. Johnson and Fats Waller. Almost inevitably he started out as a stride pianist – a swinging left hand as it ‘strides’ up and down the keyboard.

Basie began by playing in touring bands, ending up in Kansas City in 1927 where he decided to settle. He was briefly a member of Walter Page’s Blue Devils, as well as Bennie Moten’s Orchestra, the band with which Basie first recorded in October 1929. He stayed with Moten until 1935 when the bandleader died; for a glimpse into the emerging style of Basie and just how good the Moten band was, 1932’s ‘Moten Swing’ is wonderful. The band included both Hot Lips Page and Ben Webster.

Striking out on his own, Basie formed a nine-piece band, The Barons of Rhythm; among its number was Lester Young. The following year he recorded as the Count Basie Blues Five, with Jimmy Rushing on vocals, before he finally settled on Count Basie and his Orchestra in January 1937. It was probably while the band had been broadcasting on the radio shortly before this that the announcer called Basie ‘Count’, and the name stuck.

By now he was basing himself in New York and with Walter Page in the band, along with Lester Young, Buck Clayton and Jimmy Rushing, he had a superb unit. He signed for Decca and the first sides the Basie Orchestra cut were in January 1937 and they showcased the Count’s piano style. While retaining elements of the stride style with which he had grown up, he was now playing with fewer notes that gave the arrangements more ‘air’, creating what became his trademark style. A few months earlier, he had recorded for Vocalion using the pseudonym Jones Smith Incorporated as he had already signed for the Decca; among the tunes was ‘Oh Lady Be Good’, featuring Lester Young on his first session.

A few months later the band was back in the studio, and with them for the first time was a guitarist whose playing of chords across the beat would do so much to make them swing and help define what we know as the Basie sound. This was Freddie Green, and over thirty years later he was still there doing his very particular thing. Green was just one of many sidemen who made the Basie band the epitome of a swinging jazz ensemble.

In July 1937, Basie came up with a new tune, ‘One O’Clock Jump’, which it became a hit as well as becoming the band’s theme for many years. Over the years Count Basie revisited his tune on numerous occasions, reinventing it and making it one of the best-known pieces in big-band jazz. For a while in 1937 the Basie band also worked with Billie Holiday, recording ‘They Can’t Take That Away from Me’ at the Savoy Ballroom in New York City. Basie’s band was regularly on the radio and was heard coast to coast, making them one of the most popular bands in America for the next decade.

While the band did change personnel to continually improve its sound, Basie held onto the key members for longer periods than most. It was certainly a band that seemed to enjoy being together as much as they enjoyed playing together. Basie was a good leader and gave his band the environment in which to flourish as musicians, as well as to have fun doing it. Basie’ love of laughter was legendary, and as many have commented over the years that he was also a gentleman.

Key to the band’s success was the Basie rhythm section. Besides Basie’s light and airy piano and Freddie Green’s guitar, there was Walter page’s bass and the sensitive drumming of Jo Jones. Basie regularly referred to Jones as the ‘boss’, the head man in the band. Jones’ use of the hi-hat rather than the bass drum to keep the beat ‘lightened’ their sound – there’s no doubt that the Basie band made jazz more accessible to people who perhaps didn’t realize they liked jazz.

By 1950, things in the big-band business were not good and Basie called it a day. For two years he had an eight-piece band, but then in 1952, he resurrected his orchestra, unofficially calling it the New Testament band. He also recorded with Norman Granz’s Clef label for the first time – it was a session with tenor saxophonist Illinois Jacquet on which some of the Basie stalwarts played and Count played the organ. Shortly afterwards, he did sessions for an album called The Swinging Count (1956) and throughout the 1950s and ’60s, he did many sessions for Verve. Among the best were sessions with singer Joe Williams in 1955 that were captured on the album, Count Basie Swings – Joe Williams Sings, and another later in the summer for the album that became April In Paris (1956). Check out The Complete Clef & Verve Fifties Studio Recordings for a fantastic view of an American legend at his peak.

He became, along with Armstrong and Ellington, one of the few jazz players to gain a wide-ranging level of recognition around the world. In 1954, he made the first of many visits to Europe and three years later Basie played London’s prestigious Royal Festival Hall; he was so good at the Royal Festival Hall that Princess Margaret who went to see his 6 p.m. show went back to see him again at 9 p.m.

The Basie band’s secret weapon during the 1950s was Neal Hefti who did most of the arrangements. He had played the trumpet for Woody Herman’s band and later worked with Frank Sinatra, and had his own band as well as composing the Batman theme. According to Miles Davis, “If it weren’t for Neal Hefti, the Basie band wouldn’t sound as good as it does. But Neal’s band can’t play those same arrangements nearly as well.” Basie always surrounded himself with the most talented people. Among his sixties recordings are Basie’s Beatle Bag and a superb album with Ella Fitzgerald, A Perfect Match.

By 1962, the Basie band, as well as performing and releasing albums on their own, began a relationship with Frank Sinatra that lasted four years. In October the two legends went into the studio in Los Angeles for three days to work on a new album. On entering the studio Sinatra said: “I’ve waited twenty years for this moment.” Somewhat appropriately the first song they did together that day was ‘Nice Work If You Can Get It’; it’s classic Sinatra, made perfect by Basie and a great Hefti arrangement. When the album, simply called Sinatra–Basie, came out in early 1963, it sold better than anything the singer had done for several years. They also recorded It Might As Well Be Swing (1964), and after Sinatra and Basie played the Newport Festival in 1965 they were booked into the Sands in Las Vegas – their show was recorded and released as Sinatra At The Sands (1966). It’s been called the definitive portrait of Sinatra in the 1960s; it’s true, but it’s likewise a great window on the Basie band.

The Basie band kept working into the 1970s, with the Count in his yachting cap that he had adopted in the 1960s, but his age and changing fashion eventually caught up with him. Count Bill Basie died in Hollywood on April 26 1984. His legacy is enormous. He may well have introduced more people over several generations to the sound of big bands than any other bandleader – and by definition, he introduced so many to jazz.

Accessibility was key to his enduring appeal, but so was his ability to keep a great band together through his consideration for his fellow musicians and, in turn, the affection in which everyone held Count. Today there’s no band that plays ‘April in Paris’ without the musicians thinking of the man who just loved to swing.

Words: Richard Havers

petèr paul s

August 7, 2020 at 12:46 am

My grandfather was antonio sbarbaro of the ODJB the first jazz drummer to record jazz in 1917 grew up with Louis armstrong he played with all the great jazz artist Edmond Hall papa jack laine

i