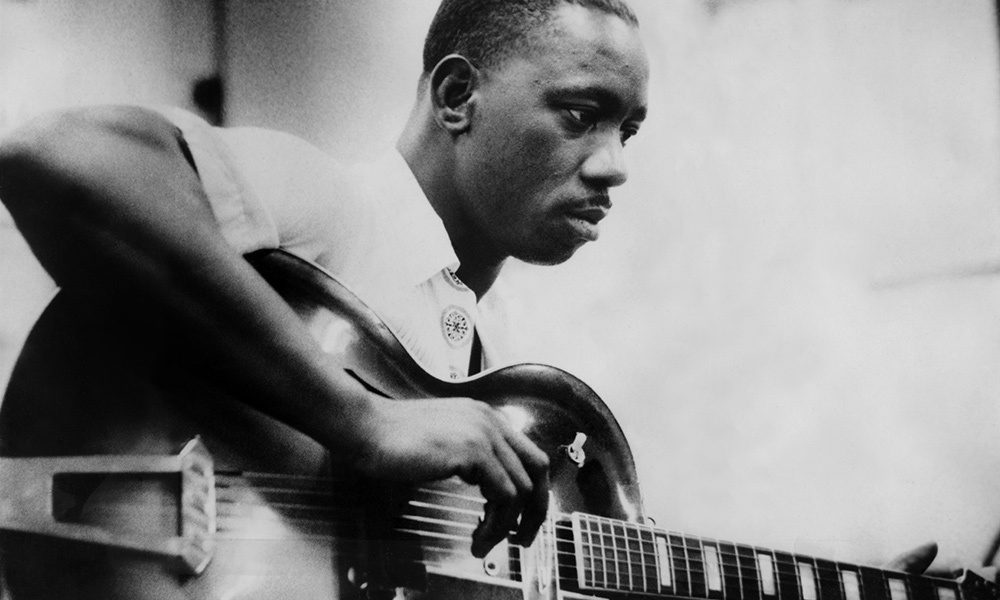

Wes Montgomery

The jazz guitarist from Indianapolis, Indiana played with a unique technique that made him one of jazz’s greatest innovators.

There is no one that has picked up a guitar and played jazz that has not been influenced by Wes Montgomery. The fact that he died relatively young has in some ways diminished his reputation. And yet his catalogue of recordings is a testament to his brilliance and along with Jimmy Smith and his Hammond B3, Montgomery did so much to encourage people, who were perhaps a little fearful, to give jazz a try.

“I learned to play listening to Wes Montgomery’s Smokin’ at the Half Note.” – Pat Metheny

John Leslie Montgomery got the name Wes when he was a teenager; it’s a corruption of his middle name. Born on 6 March 1923 in Indianapolis, Wes followed in the footsteps of his bass playing older brother, Monk, and took up the six-string guitar when he was twenty, having played a four-string guitar since he was twelve; later their piano and vibes playing younger brother, Buddy, joined the family of musicians. He learned the guitar from listening to Charlie Christian records, he was note-perfect on his hero’s solos, and also taught himself to read music.

After a spell playing in local bands, he joined Lionel Hampton’s orchestra in July 1948 and spent the next eighteen months touring and recording with the band. After Montgomery quit Hampton’s band in January 1950 he went back to Indianapolis and nothing more was heard from him musically until 1955, and then just one session for Columbia. In 1957 the three brothers and trumpeter Freddie Hubbard recorded together. For the next two years the Montgomery Brothers recorded for World Pacific Jazz and Wes, in particular, began to build a reputation as a gifted guitarist.

In October 1959 the Wes Montgomery Trio recorded for the Riverside label in New York City and over the next year or so, as well as recording under his own name, Wes worked in the studio with singer Jon Hendricks, trumpeter Nat Adderley, saxophonists Harold Land and Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, George Shearing, Milt Jackson as well as a number of sessions with his brothers. In the Downbeat poll for best guitarist, he was pre-eminent from this time onwards; his much loved, unique, tone was in part derived from using his thumb rather than a plectrum.

Montgomery’s work is characterised by the way he built his solos from the melodies. His original imagination created seemingly simple solos that often surprises the listener but always felt just right.

From 1962 he recorded mostly under his own name for the Riverside label and recorded some acclaimed albums including The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery in 1960 with pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Percy Heath and drummer Albert ‘Tootie’ Heath. It features two of Montgomery’s best-known compositions, ‘Four on Six’ and ‘West Coast Blues.’ He was signed by Verve late in 1964 and his first sessions with Johnny Pate’s orchestra in November produced the album, Movin’ Wes.

In March 1965 he recorded with Don Sebesky’s Orchestra at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio and the tracks made up the album Bumpin’ becoming the first of his ten albums to make the Billboard Pop charts. The album proved difficult for Montgomery to make as when he was recording with the full orchestra he was unable to get the results he wanted. Sebesky came up with the idea of Montgomery recording with a small group to which orchestral overlays were added. Over the next three years, Wes was rarely off the charts with albums including Tequila (1966), arranged by Claus Ogerman, California Dreaming (1967) and Jimmy & Wes The Dynamic Duo, an album recorded with Jimmy Smith.

One of his most appreciated Verve albums is Smokin’ at the Half Note (1965) that was recorded at the New York City club with the Wynton Kelly Trio. Although both this and his Further Adventures of Jimmy and Wes failed to chart they are fine albums and certainly at the jazzier end of the spectrum, which may well account for their lower sales. Both these albums are representative of Montgomery’s club appearances throughout his career when he played in small group settings rather than the orchestral accompaniment that he so often appeared with on record.

In late 1967 Montgomery signed for Creed Taylor’s CTI Records, a subsidiary of A&M Records, and had his most successful record on the Billboard charts when A Day In The Life reached No.13 and stayed on the charts for well over a year on its way to becoming the best selling jazz album of 1967.

On 15 June 1968, just a month after his last ever recording session for A&M, and shortly after returning from a tour with his quartet, Montgomery woke up feeling unwell; within minutes he had a heart attack and died instantly. He was forty-five years old and at the peak of both his fame and success.

Montgomery’s influence on jazz guitar cannot be understated. Joe Pass said, “To me, there have been only three real innovators on the guitar—Wes Montgomery, Charlie Christian, and Django Reinhardt.” It is not just jazz guitarists that recognise Montgomery’s talent, among the rock fraternity; Stevie Ray Vaughan, Joe Satriani and Jimi Hendrix have all acknowledged his influence. Lee Ritenour, who recorded the 1992 album Wes Bound, also named his son Wesley.

Words: Richard Havers