Toasts, Boasts And Coasts: Hip-Hop On The Frontline

Hip-Hop artists have always waged war on conventional music – and each other. Braggadocio is always there, but it got out of control and ended in tragedy.

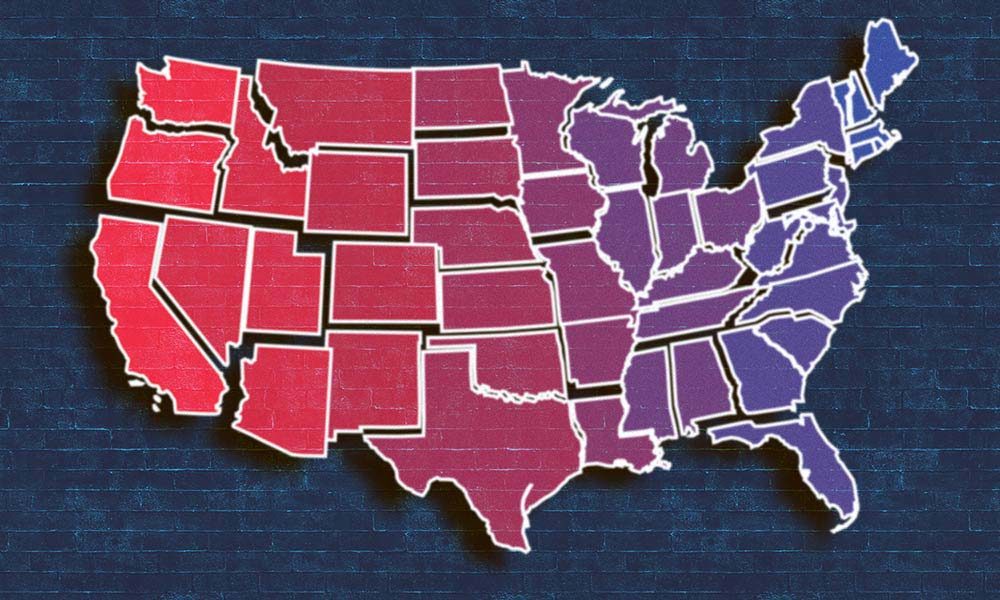

For all its lyrical self-awareness and laudable attempts to bring its adherents together, hip-hop was built on conflict. The music’s fans see it as a movement, and they are right: this remains a sound that thrives on the defiance of the usual rules of pop, expressing itself in any way it sees fit. But its war on music’s conventions is matched by outbreaks of civil war within its ranks – none more ferocious or bloody than the War Of The Coasts.

For all its lyrical self-awareness and laudable attempts to bring its adherents together, hip-hop was built on conflict. The music’s fans see it as a movement, and they are right: this remains a sound that thrives on the defiance of the usual rules of pop, expressing itself in any way it sees fit. But its war on music’s conventions is matched by outbreaks of civil war within its ranks – none more ferocious or bloody than the War Of The Coasts.

Hip-hop was originally a territorial phenomenon, with crews that followed DJs from block party to park jam around Brooklyn and the Bronx. Loyalty mattered, and adherents to a rap crew needed to know that those who took the mic were exciting enough to deserve that loyalty. So hopeful party poets who grabbed the mic had just a few lines of rhyme to prove they were true MCs. The origins of hip-hop remain debated, but what’s certain is the mobile DJs who ruled the street sound of New York in the 70s – the likes of Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash and MC Coke La Rock – were heavily influenced by the culture of 70s reggae, where the concept of a clash between sound systems drove the music and MCs fought on the microphone to show their supremacy. (For examples on record, check out I Roy and Prince Jazzbo’s series of mid-70s diss singles, or, more simply, Shorty The President’s President Mash Up The Resident.)

What was called a “clash” in Jamaican music became a “battle” in rap, and Herc, born in Jamaica, and his talented followers (including Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa, among others), did much to promote the idea, organising confrontations over breaks across the Bronx. So when New York’s rappers first took the mic in public in the 70s, they had two things on their minds: to rock the crowd with party lingua, and prove themselves superior to their rivals. Hence the braggadocio of Master Gee: “I’m going down in history as the baddest rapper there could ever be,” on the first rap record most music fans heard, Sugarhill Gang’s ‘Rappers Delight’. Rap may have originated at a party, but from the get-go it was dog-eat-doggy-dog out there.

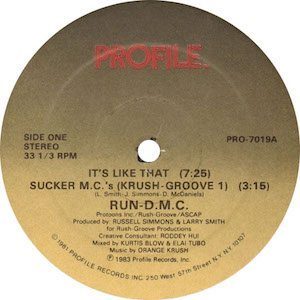

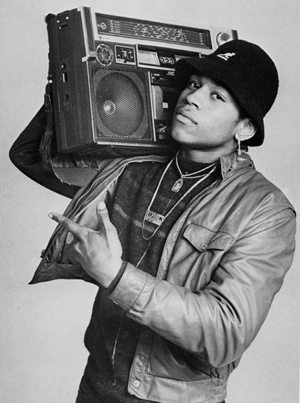

The concept of proving yourself and taking on all comers became part of hip-hop’s DNA, surfacing regularly: Run-DMC’s ‘Sucker MCs’, LL Cool J’s ‘Mama Said Knock You Out’, EPMD’s ‘Strictly Business’, Ice-T’s ‘Rhyme Pays’… you couldn’t be an MC without promising to crush your rivals on a regular basis.

The concept of proving yourself and taking on all comers became part of hip-hop’s DNA, surfacing regularly: Run-DMC’s ‘Sucker MCs’, LL Cool J’s ‘Mama Said Knock You Out’, EPMD’s ‘Strictly Business’, Ice-T’s ‘Rhyme Pays’… you couldn’t be an MC without promising to crush your rivals on a regular basis.

Originally those rivals dissed as “suckers” were on the next mic – or the next block, the next sound system. When hip-hop became a major business in the mid-80s, they became the MCs in another producer’s stable, or in another city altogether. And while most rappers knew it was just something in hip-hop’s blood, or a tradition that had to be respected, or perhaps just a way to win respect or publicity, those who were not as aware of the music’s history, or who got carried away with their image as the baddest microphone pimp in the business, took their beefs further – eventually with tragic consequences.

It seems clear today that New York was not ready for the rise of West Coast rap in the mid-80s. After all, the city had had it pretty much all its own way for half a decade or more. Like British military men believing at the start of the 20th Century that it was likely to be at war with its traditional enemy (France) rather than its blood relative (Germany), the East Coast’s rappers were fighting parochial battles while the West Coast built up its war machine. And the East could be forgiven for believing that everything was going to continue to run to its advantage: practically every development in rap up to 1986 was a product of the five boroughs. Party rap, electro, rock-rap, conscious “edutainment” hip-hop, female MCs, political rappers: you name it, it started there. New York had an apparently endless pipeline of fresh talent to power each successive development in hip-hop: Whodini, Mantronix, Roxanne Shante, Luv Bug Hurby, Marley Marl, Eric B & Rakim, Pete Rock & CL Smooth, Boogie Down Productions, Just Ice, Ultramagnetic MCs… the genius of East Coast rap just kept on coming.

It seems clear today that New York was not ready for the rise of West Coast rap in the mid-80s. After all, the city had had it pretty much all its own way for half a decade or more. Like British military men believing at the start of the 20th Century that it was likely to be at war with its traditional enemy (France) rather than its blood relative (Germany), the East Coast’s rappers were fighting parochial battles while the West Coast built up its war machine. And the East could be forgiven for believing that everything was going to continue to run to its advantage: practically every development in rap up to 1986 was a product of the five boroughs. Party rap, electro, rock-rap, conscious “edutainment” hip-hop, female MCs, political rappers: you name it, it started there. New York had an apparently endless pipeline of fresh talent to power each successive development in hip-hop: Whodini, Mantronix, Roxanne Shante, Luv Bug Hurby, Marley Marl, Eric B & Rakim, Pete Rock & CL Smooth, Boogie Down Productions, Just Ice, Ultramagnetic MCs… the genius of East Coast rap just kept on coming.

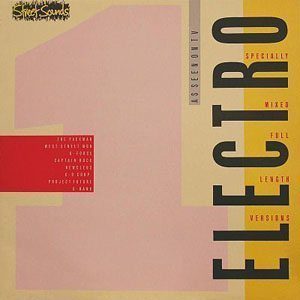

Hip-hop from beyond New York, however, took some time to catch up, though it was starting to get noticed on other scenes worldwide. UK Fresh 86, the largest hip-hop event held in London to this day, featured Philly’s Steady B, a fine set from Dr Dre’s World Class Wreckin’ Cru out of LA, and Sir Mix-A-Lot, who was making waves all on his own out of Seattle – though it’s doubtful that any regional distinctions really came across to a UK audience armed with whistles and ready to party. The event was partly promoted by the Street Sounds label, whose Electro albums pretty much dictated what the average British wannabe B-boy was going to hear in the early-to-mid-80s, much as the Motown Chartbusters and Tighten Up albums had done for previous generations.

Street Sounds had been enterprising in locking on to the electro market, but it was not a high-budget operation, and while it was alert to what was selling on import, its choices as to which tracks to snap up were perhaps dictated by how much they would cost and who was willing to deal with it. Hence records by LA talents such as Egyptian Lover and CIA, a group which featured future N.W.A lynchpin Ice Cube, would appear on Electro albums alongside those of New Yorkers UTFO and Doug E Fresh, because they were big on import and affordable to license, rather than because they represented any particular scene or musical marque. But West Coast hip-hop was now being heard beyond its area code – even if it was passing unnoticed in NYC – and California’s hip-hop style was starting to coalesce, even if its artists still looked towards Eastern acts for inspiration.

Street Sounds had been enterprising in locking on to the electro market, but it was not a high-budget operation, and while it was alert to what was selling on import, its choices as to which tracks to snap up were perhaps dictated by how much they would cost and who was willing to deal with it. Hence records by LA talents such as Egyptian Lover and CIA, a group which featured future N.W.A lynchpin Ice Cube, would appear on Electro albums alongside those of New Yorkers UTFO and Doug E Fresh, because they were big on import and affordable to license, rather than because they represented any particular scene or musical marque. But West Coast hip-hop was now being heard beyond its area code – even if it was passing unnoticed in NYC – and California’s hip-hop style was starting to coalesce, even if its artists still looked towards Eastern acts for inspiration.

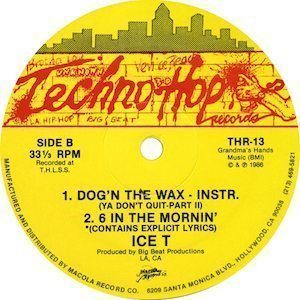

The record that is often cited as the cornerstone of the West Coast style is ‘6 In The Mornin’’, which detailed run-ins with the police as well as considerable B-boy/pimp style. Released in 1986, and the fifth single by long-exiled New Jersey MC Ice-T, you can hear the influence of Philadelphia’s Schoolly D all over it. But Schoolly was a powerful source to draw on. He was under-recorded and not heard anywhere near enough; fiercely independent, he gave no quarter to his rivals and spoke of the “gangsta” life he saw on the streets. While New York gave his mad skills a respectful nod, out West those skills delivered a whole style for Ice-T and N.W.A, and in Houston, Texas, Geto Boys also took a lead from what Schoolly achieved. Eazy E’s ‘The Boyz-N-The Hood’ (1987, written by Ice Cube) owed plenty to Ice-T’s breakthrough tune – and therefore Schoolly too. The West Coast style was ready to roll, even if the East helped boot it up.

The record that is often cited as the cornerstone of the West Coast style is ‘6 In The Mornin’’, which detailed run-ins with the police as well as considerable B-boy/pimp style. Released in 1986, and the fifth single by long-exiled New Jersey MC Ice-T, you can hear the influence of Philadelphia’s Schoolly D all over it. But Schoolly was a powerful source to draw on. He was under-recorded and not heard anywhere near enough; fiercely independent, he gave no quarter to his rivals and spoke of the “gangsta” life he saw on the streets. While New York gave his mad skills a respectful nod, out West those skills delivered a whole style for Ice-T and N.W.A, and in Houston, Texas, Geto Boys also took a lead from what Schoolly achieved. Eazy E’s ‘The Boyz-N-The Hood’ (1987, written by Ice Cube) owed plenty to Ice-T’s breakthrough tune – and therefore Schoolly too. The West Coast style was ready to roll, even if the East helped boot it up.

Meanwhile, back out East, it was business as usual. Hip-hop bombs kept dropping during 1987. A hit rap album could shift 250,000 copies at this point and, as Eazy E’s 12”, alongside N.W.A’s Panic Zone EP, slipped out from the West amid little hype, New York was blessed with rap riches that lifted the music to new heights. There were Eric B & Rakim’s Paid In Full, Boogie Down Productions’ Criminal Minded, Public Enemy’s debut, Yo! Bum Rush The Show, and fine singles from Stetsasonic, Jungle Brothers, Ultramagnetic MCs and more. The following year, NYC unleashed further powerful missives from Public Enemy, Biz Markie, Eric B & Rakim, EPMD and BDP. However, on 9 August 1988, hip-hop took a change of direction and suddenly found itself with two centres of excellence.

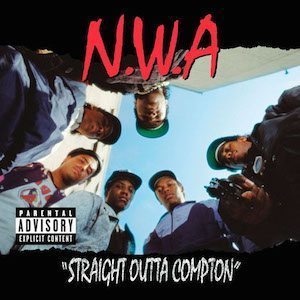

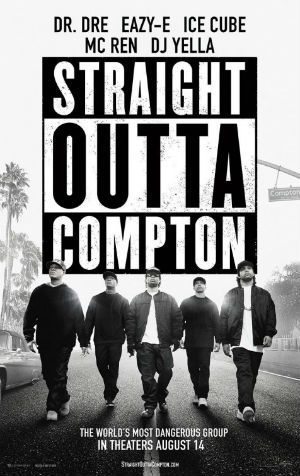

N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton didn’t exactly break the mould; there was nothing new about sampling, and other acts had pointed the way it was headed – as previously noted. But it goes without saying that a band driven by Dr Dre, Ice Cube and MC Ren would have plenty to say for itself, while Eazy E’s voice was dripping with acidic bile. DJ Yella’s co-production was not perhaps as polished or as cutting-edge as the work of, say, The Bomb Squad, who put together Public Enemy’s records, but it was effective in the extreme because it was built to be funky, yet allow the spotlight to fall directly on the lyrics.

N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton didn’t exactly break the mould; there was nothing new about sampling, and other acts had pointed the way it was headed – as previously noted. But it goes without saying that a band driven by Dr Dre, Ice Cube and MC Ren would have plenty to say for itself, while Eazy E’s voice was dripping with acidic bile. DJ Yella’s co-production was not perhaps as polished or as cutting-edge as the work of, say, The Bomb Squad, who put together Public Enemy’s records, but it was effective in the extreme because it was built to be funky, yet allow the spotlight to fall directly on the lyrics.

Those lyrics’ acute focus was on what those in its intended audience saw as the harsh reality of ghetto life. But those who were not in its catchment area saw the rhymes as nigh-on criminal, full nihilism, disrespect of women, authority and, specifically, the police. The album worked: it was a sensation in a way that no hip-hop record had been before, and went platinum by word of mouth (and notoriety, of course), because, naturally, it received no airplay. Straight Outta Compton pulled together virtually all its elements from East Coast rap, but had honed them to diamond-hard perfection and reassembled them to reflect gang life in the California ghetto.

Those lyrics’ acute focus was on what those in its intended audience saw as the harsh reality of ghetto life. But those who were not in its catchment area saw the rhymes as nigh-on criminal, full nihilism, disrespect of women, authority and, specifically, the police. The album worked: it was a sensation in a way that no hip-hop record had been before, and went platinum by word of mouth (and notoriety, of course), because, naturally, it received no airplay. Straight Outta Compton pulled together virtually all its elements from East Coast rap, but had honed them to diamond-hard perfection and reassembled them to reflect gang life in the California ghetto.

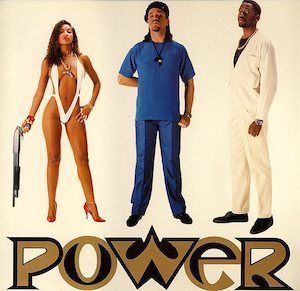

There was now competition for NYC’s hegemony, and N.W.A’s album wasn’t the only challenge it faced across the country in 1988. Geto Boys issued their debut long-player, though they had yet to arrive at their successful formula. Rather more pertinently, Ice-T’s second LP, Power, was released in September and hit No.36 in Billboard’s album listings (one rung higher than N.W.A had managed), and its performance on the rap chart was comparable, even if Straight Outta Compton eventually shifted far more copies and made a greater cultural impact in the long term.

The focus of an outraged establishment’s attention fell firmly on these two acts, who were attacked by everyone from the FBI to groups representing “family interests”. Rap was now being blamed for black America’s ills, and the scapegoats were all from Los Angeles. Handily, this provided all the promotion these artists needed. Another unintended bonus was the new Parental Advisory stickers that adorned rap albums, which were practically a come-on: buy this album, your parents will hate it. Gangsta rap from the West was now the perfect musical soundtrack for America’s disaffected teens.

The focus of an outraged establishment’s attention fell firmly on these two acts, who were attacked by everyone from the FBI to groups representing “family interests”. Rap was now being blamed for black America’s ills, and the scapegoats were all from Los Angeles. Handily, this provided all the promotion these artists needed. Another unintended bonus was the new Parental Advisory stickers that adorned rap albums, which were practically a come-on: buy this album, your parents will hate it. Gangsta rap from the West was now the perfect musical soundtrack for America’s disaffected teens.

Just to make things more complicated for those New York rappers who had felt they were set up for life, the city’s sound was about to change. Jungle Brothers’ debut album, Straight Out The Jungle, and Lakim Shabazz’s Pure Righteousness presented different takes on hip-hop: one funky, sly and humorous, the other hard-edged, unfussy and serious. The former was the precursor of De La Soul’s “DAISY Age” sound; the latter a downbeat, hard-edged option that took the music back to a break and a highly-charged rhyme. New York offered options, but the public voted with its cash and bought the gangsta sound instead.

Instead of going back to basics, the radical development of East Coast hip-hop continued unabated. It was admirable: NYC could have rolled up its breakdance lino and made its own variants on California styles, but instead 1989 offered Gang Starr’s debut, No More Mr Nice Guy, ushering in the brilliant fusion that was “jazz-rap”. There was also 3rd Bass’ The Cactus Album, one of the most credible collections by (mostly) white hip-hoppers to date, along with Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique, and further intrigues from Jungle Brothers and BDP. But the record-buying Benjamins went to N.W.A, Ice-T’s The Iceberg, and the rap sensation of the year, Tone Lōc, whose Lōc’ed After Dark was a US pop chart No.1 – all artists from the West. Even De La Soul’s much-garlanded 3 Feet High And Rising, an opening salvo which today is lavished with “greatest-ever” accolades, only made No.24 on Billboard’s pop listings. In commercial terms – and in the sense of who was really carrying hip-hop’s motherlode – the West won 1989 hands down.

Instead of going back to basics, the radical development of East Coast hip-hop continued unabated. It was admirable: NYC could have rolled up its breakdance lino and made its own variants on California styles, but instead 1989 offered Gang Starr’s debut, No More Mr Nice Guy, ushering in the brilliant fusion that was “jazz-rap”. There was also 3rd Bass’ The Cactus Album, one of the most credible collections by (mostly) white hip-hoppers to date, along with Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique, and further intrigues from Jungle Brothers and BDP. But the record-buying Benjamins went to N.W.A, Ice-T’s The Iceberg, and the rap sensation of the year, Tone Lōc, whose Lōc’ed After Dark was a US pop chart No.1 – all artists from the West. Even De La Soul’s much-garlanded 3 Feet High And Rising, an opening salvo which today is lavished with “greatest-ever” accolades, only made No.24 on Billboard’s pop listings. In commercial terms – and in the sense of who was really carrying hip-hop’s motherlode – the West won 1989 hands down.

W hich makes it a little curious that it was an LA-based easterner who apparently kicked off rap’s War Of The Coasts. It remains unclear what Ice-T was trying to achieve when he dissed LL Cool J in ‘I’m Your Pusher’, the most-heard song from his album Power, though he wasn’t the only MC to do so: LL was under fire for recording the romantic hit ‘I Need Love’, and was barracked and booed at a gig in London when he launched into it. Ice-T also wrote ‘Girls LGBNAF’, a sneer aimed firmly at LL’s love raps, and later claimed he was just trying to stir up a bit of a fuss with a rival, perhaps as self-motivation or as a publicity device. Either way, as any self-respecting rapper would have to, LL did not let it slide, replying on 1990’s ‘To Da Break Of Dawn’ with lyrics that mocked Ice-T’s lyrical abilities, personal style, background and even his rhythmically admired girlfriend, Darlene Ortiz, who had posed on the cover of Power in a revealing swimsuit – while holding a shotgun.

hich makes it a little curious that it was an LA-based easterner who apparently kicked off rap’s War Of The Coasts. It remains unclear what Ice-T was trying to achieve when he dissed LL Cool J in ‘I’m Your Pusher’, the most-heard song from his album Power, though he wasn’t the only MC to do so: LL was under fire for recording the romantic hit ‘I Need Love’, and was barracked and booed at a gig in London when he launched into it. Ice-T also wrote ‘Girls LGBNAF’, a sneer aimed firmly at LL’s love raps, and later claimed he was just trying to stir up a bit of a fuss with a rival, perhaps as self-motivation or as a publicity device. Either way, as any self-respecting rapper would have to, LL did not let it slide, replying on 1990’s ‘To Da Break Of Dawn’ with lyrics that mocked Ice-T’s lyrical abilities, personal style, background and even his rhythmically admired girlfriend, Darlene Ortiz, who had posed on the cover of Power in a revealing swimsuit – while holding a shotgun.

Battle was on. It was perhaps first meant as a bit of a laugh, but the War Of The Coasts would blow up beyond anyone’s expectations.

Before we go on, it’s worth reminding ourselves that rap had long specialised in turf wars. LL had a beef with Kool Moe Dee during the 80s, and attacked Oakland, California, rapper MC Hammer on record. Another unseemly spat, The Bridge Wars, lasted longer. It was a battle over the roots of hip-hop between two areas of New York: Queensbridge, as represented by Marley Marl’s Juice Crew, and South Bronx, defended by KRS-One of Boogie Down Productions. The much-dissed yet dazzlingly talented LL Cool J also got dragged into this feud – with both sides citing him to support their argument. In a different dispute, in 1991 KRS-One forced Jersey City bliss-hoppers PM Dawn off stage, taking over the show in disgust at a comment that the latter’s frontman, Prince Be, had made in an interview. Clearly, if East Coast stars were ready to battle each other, they’d show no mercy on their new rivals from the West.

Before we go on, it’s worth reminding ourselves that rap had long specialised in turf wars. LL had a beef with Kool Moe Dee during the 80s, and attacked Oakland, California, rapper MC Hammer on record. Another unseemly spat, The Bridge Wars, lasted longer. It was a battle over the roots of hip-hop between two areas of New York: Queensbridge, as represented by Marley Marl’s Juice Crew, and South Bronx, defended by KRS-One of Boogie Down Productions. The much-dissed yet dazzlingly talented LL Cool J also got dragged into this feud – with both sides citing him to support their argument. In a different dispute, in 1991 KRS-One forced Jersey City bliss-hoppers PM Dawn off stage, taking over the show in disgust at a comment that the latter’s frontman, Prince Be, had made in an interview. Clearly, if East Coast stars were ready to battle each other, they’d show no mercy on their new rivals from the West.

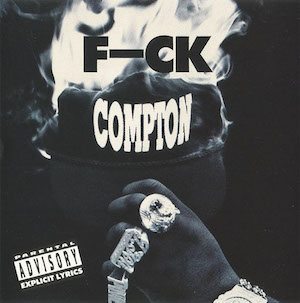

In 1991, the California/New York row shifted up a couple of gears. Tim Dog, an MC from the Bronx, directed his considerable wrath at an entire city within Los Angeles county. ‘F__k Compton’, about as heavy a hip-hop cosh as could be imagined at the time, was a sensation. Tim Dog’s cited motivation was frustration at what he perceived as the music business’ disinterest in New York rap while favouring the music of the West Coast, where artists such as Compton’s Most Wanted, Too $hort, DJ Quik and Above The Law had quickly risen to fame in the wake of Straight Outta Compton.

Doubtless Dog’s record was also intended as a shortcut to getting heard: his previous group, Ultramagnetic MCs, recorded classic after classic of probing hip-hop in the mid-80s but never rose beyond underground fame. ‘F__k Compton’ took care to diss Dr Dre, Eazy E, Michel’le and MC Ren, though Ice Cube and Ice-T both dodged a bullet. Tim Dog’s debut full-length aural dissertation, Penicillin On Wax, took things further, duplicating a beat that N.W.A had used on their Efil4zaggin album and amending it, bragging that “I stole your beat and made it better,” and calling the group, well, felines. LA hip-hop icon DJ Quik was another target, and in one skit Dog appeared to be giving Quik more than just a verbal pounding.

Doubtless Dog’s record was also intended as a shortcut to getting heard: his previous group, Ultramagnetic MCs, recorded classic after classic of probing hip-hop in the mid-80s but never rose beyond underground fame. ‘F__k Compton’ took care to diss Dr Dre, Eazy E, Michel’le and MC Ren, though Ice Cube and Ice-T both dodged a bullet. Tim Dog’s debut full-length aural dissertation, Penicillin On Wax, took things further, duplicating a beat that N.W.A had used on their Efil4zaggin album and amending it, bragging that “I stole your beat and made it better,” and calling the group, well, felines. LA hip-hop icon DJ Quik was another target, and in one skit Dog appeared to be giving Quik more than just a verbal pounding.

Naturally, the West’s brothers couldn’t take this insult lying down. Dr Dre replied with ‘Dre Day’, which helped introduce Snoop Doggy Dogg to the world; DJ Quik dropped ‘Way 2 Funky’, and Compton’s Most Wanted delivered ‘Another Victim’ and ‘Who’s F__kin’ Who?’. There were further ripostes from Rodney O & Joe Cooley, who cut an album called F__k New York, and the much-slighted Quik, in the company of Penthouse Players Clique, offered the afterthought ‘PS Phuk U 2’.

What may be intended as a trivial couple of wisecracking lines on their deliverer’s tongue might seem like something far more serious to the recipient in a branch of music where authenticity is key and respect is vital. When Queens rappers 3rd Bass found themselves playing a show with Boo-Yaa TRIBE, a hip-hop band of Samoan heritage from Carson, a city that borders Compton, they were warned before the show not to mention Boo-Yaa in their humorous yet fairly innocent diss song ‘The Gas Face’. Sometimes things could kick off for the most minimal of reasons: Too $hort, who moved millions of albums of his lewd yet undeniably talented talk, found himself barracked at his own record launch in New York, apparently not because of anything he’d said, but because of his California origins.

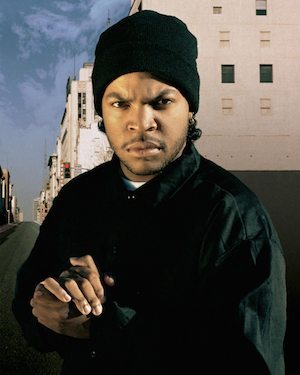

You might have thought that Ice Cube’s defection from N.W.A and his selection of The Bomb Squad as the producers of his game-changing debut album, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, would have proved the coast-to-coast spat to be pointless: here were leading talents (Public Enemy, ex-N.W.A) from both seaboards collaborating to create what was arguably the best gangsta rap album of all time. A lot of the beef amounted to little more than talk and name-calling, and logic suggests the law of sticks and stones could be applied… but bear in mind that words are the currency of rap, and currency is coveted; people live and die for it, as a bloody escalation of the East-West wars in the 90s would make clear.

You might have thought that Ice Cube’s defection from N.W.A and his selection of The Bomb Squad as the producers of his game-changing debut album, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, would have proved the coast-to-coast spat to be pointless: here were leading talents (Public Enemy, ex-N.W.A) from both seaboards collaborating to create what was arguably the best gangsta rap album of all time. A lot of the beef amounted to little more than talk and name-calling, and logic suggests the law of sticks and stones could be applied… but bear in mind that words are the currency of rap, and currency is coveted; people live and die for it, as a bloody escalation of the East-West wars in the 90s would make clear.

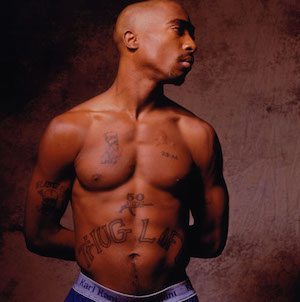

The rise of Tupac Shakur from Digital Underground’s dancer to the hip-hop icon of the 90s was a trajectory that many in the business must have envied. Though a sensitive literary soul who attended drama classes, admired Shakespeare and often displayed a strong social conscience, 2Pac invested heavily in hip-hop’s culture of rivalry. He could have been a peacemaker between the coasts, having been born and partly raised in East Harlem, New York, before moving to Marin City, California, but it was not to be.

The rise of Tupac Shakur from Digital Underground’s dancer to the hip-hop icon of the 90s was a trajectory that many in the business must have envied. Though a sensitive literary soul who attended drama classes, admired Shakespeare and often displayed a strong social conscience, 2Pac invested heavily in hip-hop’s culture of rivalry. He could have been a peacemaker between the coasts, having been born and partly raised in East Harlem, New York, before moving to Marin City, California, but it was not to be.

One of Tupac’s allies was the Brooklyn-based MC Biggie Smalls, aka The Notorious BIG, whose September 1994 debut album, Ready To Die, was, along with Nas’ Illmatic, the record that returned hip-hop’s centre from the West to the East. The two MCs used to hang together when Biggie’s album was being made and was rising in the charts. However, things quickly turned sour: in November ’94, Tupac was shot during a robbery at a Manhattan studio… and Biggie was on the premises at the time. In April the following year, Tupac claimed Biggie knew in advance about the heist, and implicated record executives Andre Harrell and Sean “Puffy” Combs in the affair – claims that were strenuously denied. Combs was the founder of Bad Boy Records, the label Biggie was signed to. By this time, Tupac was in jail for first-degree sexual abuse. When he got out after nine months, his bail was paid by Suge Knight, the CEO of Death Row, the company to which Tupac was now contracted for the release of three albums.

In February 1995, Biggie released ‘Who Shot Ya?’, a track that was taken as a diss of Tupac, with lyrics that included the line, “I’m Crooklyn’s finest/You rewind this, Vad Boy’s behind this.” Biggie and Sean Combs both stated that the song was recorded months before Tupac was shot, but the tune’s release was viewed as incendiary, whatever its lyrical target really was.

In February 1995, Biggie released ‘Who Shot Ya?’, a track that was taken as a diss of Tupac, with lyrics that included the line, “I’m Crooklyn’s finest/You rewind this, Vad Boy’s behind this.” Biggie and Sean Combs both stated that the song was recorded months before Tupac was shot, but the tune’s release was viewed as incendiary, whatever its lyrical target really was.

Blood had been spilled, but nothing had been settled. Yet.

Tupac struck back on record with ‘Hit ’Em Up’, ‘Bomb First (My Second Reply)’, and ‘Against All Odds’, while the rivalry between the Death Row and Bad Boy labels grew. Both companies had highly assertive and public figureheads, the two biggest acts in hip-hop, and reputations to maintain. Biggie did not directly respond to Tupac’s records, but many fans believed his track ‘The Long Kiss Goodnight’ was about Shakur, which Combs denied.

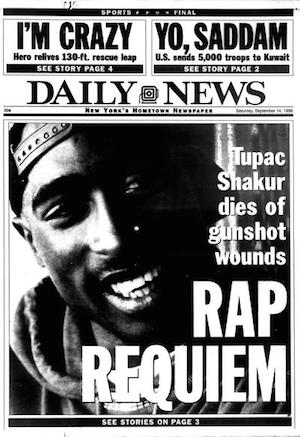

The pressure between the two parties was becoming unbearable, but hip-hop was still shocked when Tupac was murdered on 13 September 1996 in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas. On 9 March 1997, The Notorious BIG was killed in a similar hit in Los Angeles. Two of rap’s most powerful voices had been silenced, and while speculation, investigations and theories have been rife, neither crime has ever been solved.

Let’s not trivialise the murders of two of the most talented hip-hop artists of their era. A bullet is not a song, a shooting is not a diss: young men died, perhaps for their art. Comparisons to other branches of popular culture are rational but false: Al Pacino may have appeared in Scarface, but he didn’t get shot afterwards. He has never been a real-life criminal. The point about hip-hop is authenticity; it has to be believable because it is the voice of the streets. Gangsta rap all the more so: The Notorious BIG served time for drug dealing; Tupac went to jail more than once and was born into a family of political activists that endured a series of entanglements with the law.

Let’s not trivialise the murders of two of the most talented hip-hop artists of their era. A bullet is not a song, a shooting is not a diss: young men died, perhaps for their art. Comparisons to other branches of popular culture are rational but false: Al Pacino may have appeared in Scarface, but he didn’t get shot afterwards. He has never been a real-life criminal. The point about hip-hop is authenticity; it has to be believable because it is the voice of the streets. Gangsta rap all the more so: The Notorious BIG served time for drug dealing; Tupac went to jail more than once and was born into a family of political activists that endured a series of entanglements with the law.

These young men did not just talk the talk. Ready To Die, ‘Suicidal Thoughts’; Thug Life, Me Against The World – however these titles came about, they were not mere posturing. ‘Somebody’s Gotta Die’, as Biggie’s song insisted. And somebody’s gotta cry: Biggie left two children behind; both rappers left millions of heartbroken fans. Death Row and Bad Boy had further material to release by both artists after they went to meet their maker, some of which contained disses of other artists. But the war of attrition between East and West burnt out in the aftermath. Sean Combs lamented Biggie in his anthemic ‘I’ll Be Missing You’ on his No Way Out debut album, which sold millions.

It’s a long way from Ice Cube’s ‘The Drive By’ or Boo-Yaa TRIBE’s ‘Once Upon A Driveby’ to two rappers being shot dead in separate crimes of that nature. It’s an even bigger distance from that to the innocent braggadocio that once served New York’s block party MCs so well. “I’m going down in history/As that greatest rapper that could ever be” sounds utterly innocent these days. But The Sugarhill Gang’s Master Gee is still rhyming on the mic, and the musical style he helped through an uncertain birth grew into a multi-billion-dollar business.

West Coast icon Dr Dre, too, has become one of the elder statesmen of hip-hop. Inspired by the filming of Straight Outta Compton, the acclaimed 2015 biopic that re-examined N.W.A’s impact in the late 80s and early 90s, he cut Compton, a modern-day update on the West Coast gangsta sound he helped usher in. The album is widely rumoured to mark his retirement from hip-hop’s frontline fray. Among guest turns from Ice Cube and Snoop Dogg were stand-out contributions from Kendrick Lamar, who, with his albums Good Kid, MAAD City and To Pimp A Butterfly, has emerged as a new West Coast icon, flying the flag for both Compton and unity.

West Coast icon Dr Dre, too, has become one of the elder statesmen of hip-hop. Inspired by the filming of Straight Outta Compton, the acclaimed 2015 biopic that re-examined N.W.A’s impact in the late 80s and early 90s, he cut Compton, a modern-day update on the West Coast gangsta sound he helped usher in. The album is widely rumoured to mark his retirement from hip-hop’s frontline fray. Among guest turns from Ice Cube and Snoop Dogg were stand-out contributions from Kendrick Lamar, who, with his albums Good Kid, MAAD City and To Pimp A Butterfly, has emerged as a new West Coast icon, flying the flag for both Compton and unity.

The last word should go to one of the participants in The Bridge Wars, a conflict of attrition which reached a truce in 2007 when Marley Marl and KRS-One came together to make the Hip Hop Lives album. In 1989, KRS-One was the pivotal figure in the charitable Stop The Violence Movement, and his lyrics in its single ‘Self Destruction’ included the following: “To crush the stereotype, here’s what we did/We got ourselves together/So that you could unite and fight for what’s right.” Sometimes living up to an image – or down to a stereotype – can crush you.