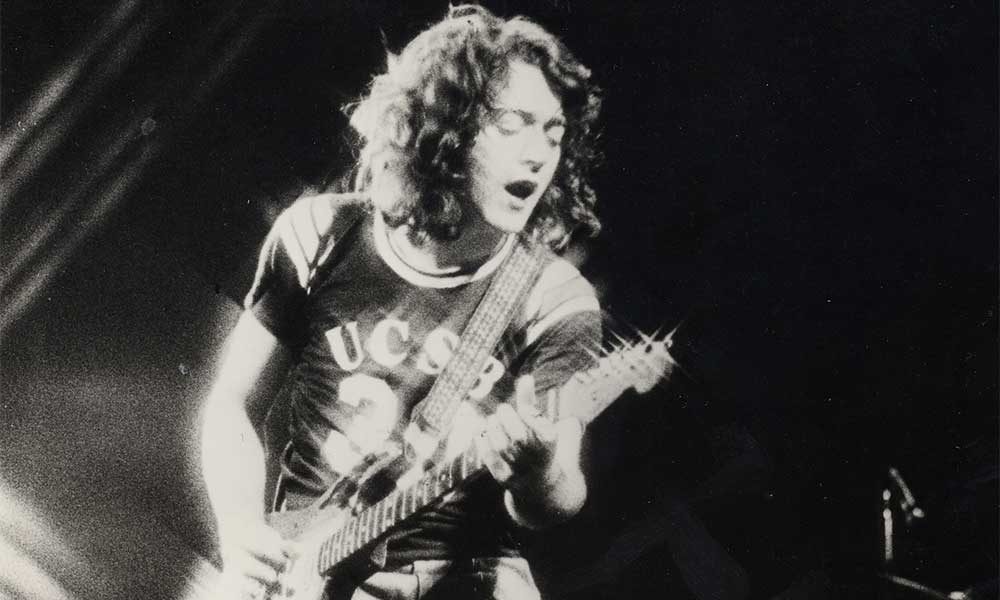

Calling Cards: How Rory Gallagher’s 70s Albums Built The Legend

Following the dissolution of Taste in 1970, Rory Gallagher kicked the new decade’s door in with a solo career that proved as inventive as it was riveting.

Rory Gallagher began turning heads as soon as Taste first trod the boards in 1966. Indeed, thanks to their young guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter’s prodigious talent, the young Irish trio quickly rose through the ranks, appearing on the bill at Cream’s widely-publicized farewell show at London’s Royal Albert Hall late in 1968 and cracking the UK Top 20 with their second album, On The Boards.

As the new decade dawned, Taste appeared to be on course for great things. Yet, despite an incendiary performance at 1970’s star-studded Isle Of Wight Festival, a combination of prosaic, business-related issues truncated the band’s career and, by the start of 1971, Rory Gallagher was ready to start afresh.

Listen to the best of Rory Gallagher on Apple Music and Spotify.

Having relocated to the UK during Taste’s latter stages, Rory retained his London base, where he auditioned for a new rhythm section. Former Jimi Hendrix Experience sidemen Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell were among those considered, but eventually Gallagher chose able Belfast duo, bassist Gerry McAvoy and drummer Wilgar Campbell, both former members of Deep Joy, who had supported Taste during Irish dates circa ’69.

Re-signing with Polydor and keen to prove himself, Gallagher’s fierce creativity led to him releasing his first two solo albums within 12 months. The product of self-produced sessions overseen by On The Boards engineer Eddie Offord, Rory’s self-titled debut appeared in May ’71 and proffered a heady mix of supercharged rockers (“Laundromat,” evergreen live favorites “Hands Up” and “Sinner Boy”) and more reflective tracks such as the Americana-flavoured “It’s You,” the delicate, Bert Jansch-esque folk of “Just A Smile” and the introspective “I Fall Apart.”

Released just six months later, Deuce was again stuffed with wall-to-wall quality. The record’s deft, jazz-tinged opener, “I’m Not Awake Yet,” showed that Gallagher refused to be pigeonholed sonically, while the diverse material again zigzagged from robust rockers (“Used To Be”) and classic, Chicago-style blues (“Should’ve Learned My Lesson”) to down-home country-blues (“Out Of My Mind”) before finally peaking with “Crest Of A Wave”: a tense, dramatic tour de force and a showcase for Rory’s astonishing slide guitar prowess.

With Deuce, Gallagher’s aim was to capture his band’s live sound, but while the album succeeded in squeezing some of their lightning into the bottle, the ferocious, elemental power Rory and company unleashed is still best experienced on the band’s 70s-era live albums.

Featuring intense versions of Junior Wells’ “Messin’ With The Kid,” Blind Boy Fuller’s “Pistol Slapper Blues” and William Harris’ “Bullfrog Blues,” 1972’s Live In Europe reflected Gallagher’s extensive knowledge of the blues in its myriad guises. The album, however, also featured incendiary versions of self-penned songs such as Deuce’s rousing “In Your Town” and the emotional, mandolin-led “Going To My Hometown,” wherein Rory namechecked two big Cork employers of the day: Ford’s car factory and Dunlop Tyres.

1972 proved a good year for Rory Gallagher, as Live In Europe yielded his first UK Top 10 success and he scooped Melody Maker’s coveted Guitarist/Musician Of The Year prize, pipping Eric Clapton to the post. After Live In Europe, however, Gallagher reshuffled his band’s line-up, retaining McAvoy but replacing Wilgar Campbell with Rod de’Ath and recruiting Belfast-born keyboardist Lou Martin.

Gallagher’s new band debuted with February 1973’s Blueprint. Recorded at Polydor’s in-house Marquee Studios in London, it was another breathtakingly eclectic set, with the brooding, eight-minute “Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son” and the zydeco-flavored “Daughter Of The Everglades” augmenting rootsy workouts, including a potent cover of Big Bill Broonzy’s “Banker’s Blues.”

Blueprint again charted inside the UK Top 20, but with Gallagher on a roll creatively, he delivered his fourth studio set, Tattoo, before the end of ’73. A sparkling collection, the album included boisterous blues-rockers “Sleep On A Clothes Line” and “Cradle Rock” (later covered by Joe Bonamassa), the anthemic “Tattoo’d Lady” and several fascinating stylistic departures such as the yearning ballad “A Million Miles Away” and the jazzy “They Don’t Make Them Like You Anymore,” during which Gallagher strapped on a bouzouki.

Suitably impressed, Rolling Stone dubbed Tattoo to be Gallagher’s “brightest and most joyful work” and declared he was “turning into a composer of note.” With the critics onside and regular tours of duty in far-flung territories from Canada to Germany, Gallagher’s fanbase was now spreading exponentially, though, as its title suggests, his landmark second live album, the double-disc Irish Tour ’74, was culled from rapturously received domestic shows in Cork, Dublin, and Troubles-torn Belfast.

Footage from these emotionally charged concerts was shot by director and former Observer music critic Tony Palmer for the feature-length concert film of the same name. Capturing Gallagher at the height of his powers, both the album and film alike are rightly regarded as high-water marks in Rory’s canon, and the best tracks – a smoldering version of “Tattoo’d Lady,” Rory’s potent cover of Tony Joe White’s “As The Crow Flies” and a blistering, 10-minute “Walk On Hot Coals” – continue to exhilarate to this day.

Despite being warmly received by fans and critics, Irish Tour ’74 proved to be Gallagher’s Polydor swansong and – after seriously considering an offer from The Rolling Stones to replace Mick Taylor early in 1975 – he signed a new solo deal with Chrysalis Records, releasing Against The Grain in October of the same year. Another raw and riveting set, the album included a dextrous acoustic version of Leadbelly’s “Out On The Western Plain” and the exuberant “Souped-Up Ford,” and it picked up further positive press in the US, with Rolling Stone favorably comparing Gallagher’s work with fellow guitar gods Eric Clapton and Alvin Lee.

Though also a reference to the wood of Gallagher’s famous Fender Stratocaster, the Against The Grain title’s dual meaning was the artist’s anti-commercial stance: his conscious decision not to compete with what he called the “smoke bomb, dry ice” arena circuit. Nonetheless, Gallagher did assent to handing the production reins of 1976’s Calling Card to Deep Purple’s Roger Glover, in a bid to pursue new musical challenges.

Consequently, Calling Card is perhaps Rory Gallagher’s most diverse release, with the jazzy title song’s lightness of touch contrasting with the brittle riffing of “Do You Read Me,” the atypically funky “Jackknife Beat” and the Hendrix-ian aggression of “Moonchild.” However, while Calling Card includes some of his band’s most decisive contributions, it would be their last release as a unit.

Before Rory’s next album arrived, he’d be forced to grapple with both line-up changes and the coming of punk…

Kjeld R.T.Larsen

December 15, 2018 at 6:06 pm

Rory Gallagher and his band,was some of the best band in those years.Here in Denmark the band was touring around and play on small and Humble Places.Allways give it for full power and close to the publik. I still have great pleasure listing to music;it’s rigth on Drums,Bass & EL-Giautar. 3 man band with a powerfull sound. It’s rock n’ roll and I like it.

Merry Christmas and Great New Year to come .