Rock’n’Roll Is Here To Stay: How Rock Has Always Rolled Us

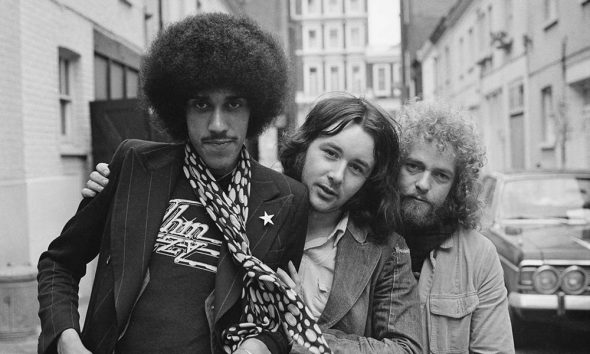

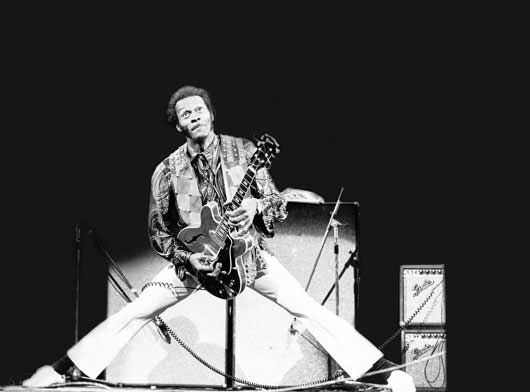

Rock’n’roll defined freedom for a new generation of youths in the 50s, spawning icons such as Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Chuck Berry, and going on to inspire The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

Rock’n’roll defined a generation’s dreams, emotions and way of life, supplying popular culture all over the globe with iconic heroes such as Elvis Presley and Mick Jagger. Though the golden age of rock may be long gone, there is still “good rockin’ tonight” in ever-evolving forms.

Rock’n’roll had solid roots in previous genres, and it could even be said to be nearly 100 years young, because it was back in September 1922 that the first mention of “rock” occurred, in a song that made clear the pulsating link between music and sex. Trixie Smith, then 27, cut a track with The Jazz Masters (a band that included jazz legend Fletcher Henderson) called ‘My Daddy Rocks Me’, in which she sang, “My daddy rocks me with a steady roll/There’s no slippin’ when he once takes hold.”

Rock’n’roll had solid roots in previous genres, and it could even be said to be nearly 100 years young, because it was back in September 1922 that the first mention of “rock” occurred, in a song that made clear the pulsating link between music and sex. Trixie Smith, then 27, cut a track with The Jazz Masters (a band that included jazz legend Fletcher Henderson) called ‘My Daddy Rocks Me’, in which she sang, “My daddy rocks me with a steady roll/There’s no slippin’ when he once takes hold.”

By the early 30s, folklorists John Lomax and his son Alan were capturing some of the songs mentioning “rock” – such as ‘Run Old Jeremiah’, with its chorus “I’ve gotta rock” – for the Library Of Congress. ‘Run Old Jeremiah’ was based on American rural South “rocking and reeling” spirituals, which had originated, as so much of popular music did, in churches. That tradition later found expression in Rock’n’roll, from Ray Charles’s ‘What’d I Say’ to The Isley Brothers’ ‘Shout’.

The rise of the record industry in that decade accelerated the way different musical styles were spread and synthesised, at a time when the foundations of the sound of later rock records were being laid. Examples of this include Big Bill Broonzy’s work in Chicago, after he switched from singing acoustically to working with horns, piano, bass and drums. In Broonzy’s case this was to satisfy an urban audience that wanted to drink and dance to loud rhythmic music in crowded clubs. But the myriad influences included the close-harmony work of the Boswell Sisters from New Orleans.

Rock also had its origins in the jazz jump music and R&B of the 40s. Rolling Stones rocker Keith Richards even went as far as to say that “rock’n’roll ain’t nothing but jazz with a hard backbeat”.

It wasn’t only black musicians who were laying the ground for rock’s arrival. In the Deep South, large white western bands such as Bob Wills And His Texas Playboys were blending blues, big-band jazz and rural country music into a potent mix that foreshadowed the sound of Carl Perkins’ ‘Blue Suede Shoes’.

It wasn’t only black musicians who were laying the ground for rock’s arrival. In the Deep South, large white western bands such as Bob Wills And His Texas Playboys were blending blues, big-band jazz and rural country music into a potent mix that foreshadowed the sound of Carl Perkins’ ‘Blue Suede Shoes’.

The key moment for the identifiable birthdate of rock came in the early 50s, when Jackie Brenston And His Delta Cats (who included Ike Turner on guitar), released the single ‘Rocket 88’ in 1951. By the middle of the decade, T Bone Walker had already pioneered the electric guitar, with shuffles that influenced guitarists from Chuck Berry to Eric Clapton. The rocking rhythm of boogie-woogie provided another form to be digested and imitated by musicians such as Jerry Lee Lewis.

These elements came together in the celebrated Elvis Presley Sun Sessions, and even with the benefit of hindsight, it’s still hard not to be impressed by his spectacular arrival in July 1954. “Nothing really affected me until Elvis,” said John Lennon.

The sessions that produced ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky’ and its B-side, ‘That’s All Right’, were a turning point in American music. Once Presley was seen live or on television, there was no forgetting him; his youthfulness and vibrancy; the powerhouse singing; the James Dean-era look to which he added the sexy swivel of the hips. Presley heralded a new era, something admitted by Bruce Springsteen, who watched in awe as a young boy when The King Of Rock appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show.

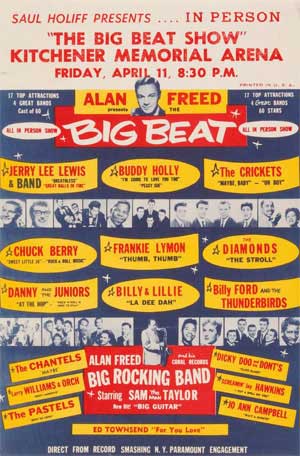

Within two years, rock was an unstoppable mystery train. Presley, Berry and Fats Domino, along with a newcomer called Little Richard, had cut memorable records and sales began to take off as rock began to attract praise from influential disciples. And no one was more significant than Alan Freed, a man who popularised the term “rock’n’roll”, though there is no definitive evidence that he actually coined the phrase.

Freed’s career started as a DJ playing records for WJW in Cleveland, when he would often thump the table with his hand to keep rhythm with the beat of the song. His radio shows were followed by live concerts called The Moondog Rock’n’Roll Party, events which broke new social ground. In these shows, artists such as Paul “Hucklebuck” Williams performed in front of a mixed-race audience in an era of segregation.

Freed’s career started as a DJ playing records for WJW in Cleveland, when he would often thump the table with his hand to keep rhythm with the beat of the song. His radio shows were followed by live concerts called The Moondog Rock’n’Roll Party, events which broke new social ground. In these shows, artists such as Paul “Hucklebuck” Williams performed in front of a mixed-race audience in an era of segregation.

Freed’s radio shows were also heard in Europe, where, by the end of the 50s, rock was beginning to be imitated. Only Billy Fury had the popular appeal to merit being dubbed the “English Elvis”. In April 1960, Decca sent the 20-year-old into the studio and he recorded a fine debut album, with many self-penned songs. Rock was starting to become its own influence and Jo Brown, the young guitarist on the record, was told by producer Jack Good to “do a Scotty Moore” and copy Presley’s celebrated guitarist.

Even though they were both imitating and paying homage to the Americans, Fury and his band, who went on to have 18 UK chart hits, forged their own distinctive style. His rise came when jukeboxes were a feature of the 2,000 Italian-style coffee bars that had opened in the UK in the two years previous to Fury’s debut.

Presley wasn’t the only American superstar taking rock’n’roll global. “If you tried to give rock’n’roll another name, you might call it Chuck Berry,” said Lennon. Berry, with his distinctive style of alternating chords, had a huge influence on the guitar styles of George Harrison and Keith Richards.

The St Louis-born musician was working as a beautician and singing in his spare time when he was sent to Chess Records on the recommendation of Muddy Waters. It was the shrewdness of Leonard Chess that helped Berry turn a country blues song called ‘Ida Red’ into the rock classic ‘Maybellene’. Freed, meanwhile, took a third share of the writing credit for the song and put his full weight behind plugging it on radio.

Berry was a gifted songwriter and smart enough to realise that songs aimed at the teenage audience – who were the core of the record-buying market – were a smart way to land a hit, hence songs such as ‘School Days’, ‘Sweet Little Sixteen’ (a tale, in its way, of fanhood) and ‘Johnny B Goode’ all had adolescent themes.

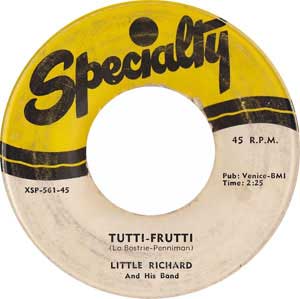

This was also a time when Little Richard made such a splash with his full-throttle singing on ‘Tutti Frutti’ (“A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-lop-bam-boom”), a song that provided a sense of sexual excitement for an audience used to the staid ways of the 50s. In a short spell, Little Richard, noted for his loud suits of gold lamé and even for wearing mascara on a movie called Mister Rock And Roll, recorded some of the seminal songs of the era, including ‘Long Tall Sally’ and ‘Good Golly Miss Molly’.

This was also a time when Little Richard made such a splash with his full-throttle singing on ‘Tutti Frutti’ (“A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-lop-bam-boom”), a song that provided a sense of sexual excitement for an audience used to the staid ways of the 50s. In a short spell, Little Richard, noted for his loud suits of gold lamé and even for wearing mascara on a movie called Mister Rock And Roll, recorded some of the seminal songs of the era, including ‘Long Tall Sally’ and ‘Good Golly Miss Molly’.

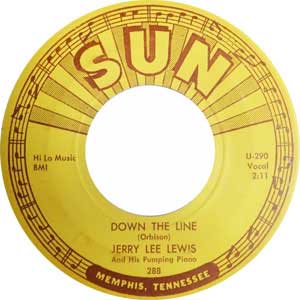

Jerry Lee Lewis was another titan of the golden era of rock’n’roll. There was a swagger and self-abandon to his performing style – he was even known to set pianos on fire with lighter fluid and use his feet to play some chords. He had three massive hits in the 50s, including ‘Great Balls Of Fire’ and ‘Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On’. Like Little Richard (who withdrew at the height of his fame to pursue religious studies in Alabama), Lewis also dropped rapidly from the height of exposure following the scandal of his marriage to a 14-year-old cousin. The man known as “The Killer” eventually bounced back and was still performing into his 80s.

Fat Domino showed that you didn’t have to be a youthful sex symbol, or outlandish on stage, to be a rock giant. Domino, who sold more than 70 million records, drew on a New Orleans heritage of music, garnered from his violin-playing father, the blues, superb ensemble jazz groups and the second-line syncopations of the Mardi Gras parade bands. He alchemised these with his own stylish piano playing and sweet voice to produce wonderful hits such as ‘The Fat Man’ and ‘Blueberry Hill’.

Another key figure in rock history is Buddy Holly, who died at 22 in 1959 – in a plane crash that also took the life of Ritchie Valens. Holly was never filmed playing music, so what remains is just the sumptuous music (he created rock’s first heroine in Peggy Sue) and the poignant black-and-white photographs. Holly inspired a host of teen idols who followed, including Bobby Vee. “Buddy Holly was the music I grew up with,” said 2016 Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan, “and he transcends nostalgia.”

Another key figure in rock history is Buddy Holly, who died at 22 in 1959 – in a plane crash that also took the life of Ritchie Valens. Holly was never filmed playing music, so what remains is just the sumptuous music (he created rock’s first heroine in Peggy Sue) and the poignant black-and-white photographs. Holly inspired a host of teen idols who followed, including Bobby Vee. “Buddy Holly was the music I grew up with,” said 2016 Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan, “and he transcends nostalgia.”

Carl Perkins, one of the quartet from Sam Phillips’s iconic Union Studio session that included Lewis, Presley and Johnny Cash, was a key part of the rockabilly craze that included notable acts such as Eddie Cochran and even such lesser luminaries as Sonny Burgess, who had a spell in the limelight and then ended up as a travelling salesman. Many were influenced by Bill Haley, the man whose B-side track ‘Rock Around The Clock’ had been such a sensation.

The fusion of rock and hillbilly was fun (Perkins called it “blues with a country beat… cat music”) and produced some great songs such as Gene Vincent’s ‘Be-Bop-A-Lula’ and Roy Orbison’s ‘Ooby Dooby’. Rockabilly was something of direct homage to Presley and it’s no coincidence that Vincent so resembled the young Presley in singing style and looks.

As we’ve seen, rock has always been a kaleidoscope of different music, evident in the way The Everly Brothers brought white country harmony to rock music. Orbison, who started off writing rock songs for other musicians (including ‘Down The Line’ for Jerry Lee Lewis) eventually made his own mark with an attractive sound that melded electric guitars, Latin rhythms and shades of classical music. It was this mix which provided the backdrop to his rich falsetto voice on classics such as ‘Only The Lonely’ or ‘Pretty Woman’.

As we’ve seen, rock has always been a kaleidoscope of different music, evident in the way The Everly Brothers brought white country harmony to rock music. Orbison, who started off writing rock songs for other musicians (including ‘Down The Line’ for Jerry Lee Lewis) eventually made his own mark with an attractive sound that melded electric guitars, Latin rhythms and shades of classical music. It was this mix which provided the backdrop to his rich falsetto voice on classics such as ‘Only The Lonely’ or ‘Pretty Woman’.

By the early 60s there were scores of interesting off-shoots of rock’n’roll, including the doo-wop of bands such as The Platters and The Coasters. In addition, there was a distinguished roster of instrumental rock bands and soloists, stretching back to The Ventures and to Duane Eddy and his style of “twangy” guitar. The formula was remarkably successful for Phoenix-born Eddy and had a far-reaching effect in the UK, inspiring The Shadows, featuring Hank Marvin playing his brand-new Fender Stratocaster.

The instrumental era reached its peak in the early 60s, but after the British invasion of The Beatles, The Who, The Kinks and The Rolling Stones, vocals once again assumed primacy in rock music.

The Beatles had been raised on American rock. Paul McCartney apparently won over Lennon’s band The Quarrymen with his unnervingly realistic Little Richard impersonation. The Beatles were steeped in rock in the way the early rockers were steeped in blues. Their dramatic 1964 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show seemed to be another landmark in the history of rock. The Liverpudlians simply captivated America.

Like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones wrote their own tunes almost from the start and, though they shared some of the same rock influences (the Stones even numbered a Buddy Holly cover among their early recordings), they also took inspiration from blues pioneers such as Bo Diddley. Lead singer Jagger was always accomplished in customising blues singing into a rock style; the Stones expressed the sheer excitement of rock’n’roll in songs such as ‘Brown Sugar’ and ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’ and had an element of danger. A 1963 article in Melody Maker asked: “Would you let your sister go with a Rolling Stone?”

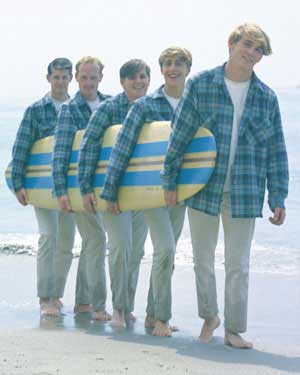

Potent imagery and advertising has always been part of rock – the slick marketing of The Monkees was probably matched by the way New Kids On The Block were marketed decades later – and The Beach Boys were sold as encapsulating the ideals of optimism, fun and independence. They were also perfect for the adolescent market of the mid-60s: for Brian Wilson, surf boards were as iconic lyrically as Chuck Berry’s automobiles.

Potent imagery and advertising has always been part of rock – the slick marketing of The Monkees was probably matched by the way New Kids On The Block were marketed decades later – and The Beach Boys were sold as encapsulating the ideals of optimism, fun and independence. They were also perfect for the adolescent market of the mid-60s: for Brian Wilson, surf boards were as iconic lyrically as Chuck Berry’s automobiles.

The US response to the British rock invasion and Swinging 60s London included Lovin’ Spoonful, the folk-rock of LA band The Byrds, and even Dylan’s conversion to rock, when the man who had been at the centre of the folk music revival caused a sensation by switching to electric.

The psychedelic rock age was not far behind this, and bands such as The Jefferson Airplane became one of the voices of the San Francisco love generation. It was also a time of excess (with musicians such as Jim Morrison of The Doors, and Janis Joplin living dangerously and dying young) and of musical ambition, with everything from The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’ to The Who and Pete Townshend’s 1969 spiritual, allegorical “rock opera” Tommy.

As the 1960s ended, rock audiences began to fragment into different factions (hard rock fans eventually gravitating to heavy metal) but one band who maintained a considerable mainstream appeal were Creedence Clearwater Revival. From 1969 to 1971, they were the most popular rock band in America.

Creedence created hit singles galore, but the music industry realised that the big money was now to be found via album sales, heralding the era of concept rock albums from bands such as Led Zeppelin, whose first six albums sold more than 15 million copies. Guitarist Jimmy Page did much to establish the unique sound of the band with his brooding solos, and ‘Stairway To Heaven’ remains a seminal song in rock history.

The 70s was also a time when the notion of the singer-songwriter took hold and enabled rock (taking in country, folk and blues influences) to move into more creative lyrical areas too, with artists such as Jackson Browne, Neil Young, Leonard Cohen, Van Morrison, Tom Waits and Joni Mitchell making a series of lastingly good albums.

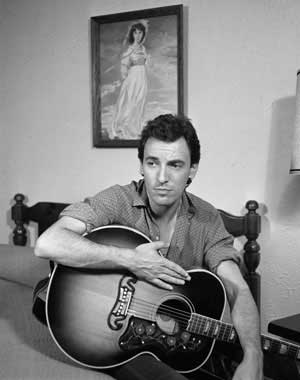

One of the key figures to emerge in this period was Bruce Springsteen, who had to cope with the label given to him by Rolling Stone magazine in 1974, when writer Jon Landau declared: “I saw rock’n’roll’s future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” Springsteen, who turned 67 in 2016, is still a major figure and it’s interesting to note that when he does impromptu medleys at concerts, he still covers songs by Little Richard, Presley and Berry.

One of the key figures to emerge in this period was Bruce Springsteen, who had to cope with the label given to him by Rolling Stone magazine in 1974, when writer Jon Landau declared: “I saw rock’n’roll’s future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” Springsteen, who turned 67 in 2016, is still a major figure and it’s interesting to note that when he does impromptu medleys at concerts, he still covers songs by Little Richard, Presley and Berry.

The man nicknamed “The Boss” rose at a time when rock offshoots were appearing in so many different and interesting formats. There was a stream of good progressive rock, with bands such as Procol Harem, Deep Purple, Emerson, Lake And Palmer, Yes and Rick Wakeman establishing deep fan bases. When decadence was once again in fashion, the avant-garde music of the likes of David Bowie, Roxy Music and Lou Reed came to the fore.

Also popular was southern boogie (Lynyrd Skynyrd, The Allman Brothers); country-rock (Gram Parsons, Eagles); LA pop-rock (Fleetwood Mac), leading to the punk rock and new wave explosions of the late 70s. And talent continued to emerge with terrific bands such as Canned Heat, Steely Dan and Free creating music that continues to be popular.

Even with all this multiplicity, traditional rock was not forgotten in the 70s. One of the great tribute albums came in October 1973, with The Band’s Moondog Matinee. Levon Helm, Robbie Robertson and co recreated songs they had played in the 60s and paid tribute to some of rock’s founding fathers, including Junior Parker and Sam Phillips (who wrote ‘Mystery Train’). They even recorded a lesser-known Chuck Berry song called ‘What Am I Living For?’, which was released in a 2001 outtakes edition.

Although they lacked the immediacy of the forces that first drove the original rockers, bands such as Sha Na Na created a rock’n’roll revival some 20 years after ‘Maybellene’. Led by founding member Frederick “Dennis” Greene, Sha Na Na started life in the 60s as an a cappella group at Columbia University, singing doo-wop classics of the 50s. The band, who played before Jimi Hendrix’s legendary set at Woodstock in 1969, found themselves back in demand in the late 70s, particularly when rock nostalgia spawned the TV show Happy Days and the movie Grease.

In the UK, a band from Leicester called Showaddywaddy (who are still touring after four decades) had chart success reviving old rock songs, especially their version of ‘Three Steps To Heaven’, a song with poignant memories for older music fans, as it was originally released in the aftermath of the death of Eddie Cochran, who died from head injuries sustained in a 1960 car crash when he was only 21.

In the UK, a band from Leicester called Showaddywaddy (who are still touring after four decades) had chart success reviving old rock songs, especially their version of ‘Three Steps To Heaven’, a song with poignant memories for older music fans, as it was originally released in the aftermath of the death of Eddie Cochran, who died from head injuries sustained in a 1960 car crash when he was only 21.

Another British act that caused a stir in the 80s was Michael Barratt, the son of a Welsh miner. After taking the stage name Shakin’ Stevens, he became the biggest-selling UK artist of the decade with a string of rockabilly hits including ‘This Ol’ House’ and ‘Green Door’. In September 2016, Stevens released his 12th studio album, called Echoes Of Our Old Times. Stevens was also astute in recognising the value of video, in an era when MTV made the visual presentation of music so important.

In the past two decades, bands have continued to fly the flag for rock music, including American rockabilly band The Stray Cats. Their influence can be seen in musicians who have kept classic rock alive in the 21st Century, including Imelda May, whose 2010 album Mayhem revived some of the original 50s twang, while, the following year, she sang on Jeff Beck’s 2011 album Rock’n’Roll Party, a tribute album to 50s rocker Les Paul. May was originally in the band Kat Men, which was formed by Stray Cats drummer Slim Jim Phantom.

In the past two decades, bands have continued to fly the flag for rock music, including American rockabilly band The Stray Cats. Their influence can be seen in musicians who have kept classic rock alive in the 21st Century, including Imelda May, whose 2010 album Mayhem revived some of the original 50s twang, while, the following year, she sang on Jeff Beck’s 2011 album Rock’n’Roll Party, a tribute album to 50s rocker Les Paul. May was originally in the band Kat Men, which was formed by Stray Cats drummer Slim Jim Phantom.

In 1990, Talking Heads frontman David Byrne declared, “As I define it, rock’n’roll is dead. The attitude isn’t dead but the music is no longer vital. It doesn’t have the same meaning. The attitude, though, is still very much alive – and it still informs other kinds of music.”

Rock does, indeed, survive, and as something more than black-and-white YouTube footage, or memorabilia in halls of fame all over the globe. Rock is an inspiration, a living and adapting form of music, played by professional bands and children all over the world.

For a form of music seen as so disposable and in-the-moment, rock’n’roll has had an inestimable lasting cultural influence. As The Rolling Stones, going strong after six decades, might say: it’s only rock’n’ roll, but we still like it.