So What Is Psychedelic Rock?

Dismissed as another momentary fad, pretty much dead in the water by mid-1968, the influence of psychedelic rock runs long and deep.

Considering it was widely dismissed at the time as merely another momentary fad, and erroneously presumed to be pretty much dead in the water by the middle of 1968, the influence of psychedelic rock runs long and deep. If one is to broadly interpret the term as a catch-all synonym for expansion of the consciousness, psychedelia has been a significant (often drug-assisted) cultural pursuit since ancient times, whether conducted with the utmost ritualistic discipline and seriousness as a means of attaining spiritual enlightenment, or simply as a hedonistic derangement of the senses.

Listen to the So What Is Psychedeleic Rock? playlist on Spotify.

The Beatles’ Revolver and the birth of psychedelic rock

For entire swathes of the record-buying public, their first encounter with psychedelic music was provided by Revolver – the game-changing Beatles album, released in August 1966, that contained so much of the exotic instrumentation and elements that came to define the form. It beguiled, ensnared, and, in some cases, disturbed the listener with its fresh, unorthodox textures: reality-shifting tape reversal techniques, tape loops, undulant sitars, and opaque lyrics.

Of course, nothing simply materializes out of nowhere. George Harrison, for example, had already been playing Indian music, introducing the sitar into The Beatles’ vocabulary on “Norwegian Wood.” And the mind-remapping initiatives eagerly showcased on Revolver represented a flowering that couldn’t help but burst forth; in a beneficially reciprocal loop, contributors to The Beatles’ expanded worldview included musical peers such as the coolly enigmatic Byrds and the previously surfing-fixated Beach Boys. Bob Dylan, too, though musically far removed from the psychedelic sounds of The Beatles and co, exerted his influence as a conundrum-generating lyricist, and, crucially, as the genial host who allegedly turned John, Paul, George, and Ringo on to marijuana in a room of New York’s Hotel Delmonico in August 1964. Furthermore, when George Harrison’s dentist irresponsibly spiked the coffees of Harrison, John Lennon, and their wives with LSD at a dinner party in April 1965, his recklessness would have profound implications.

As is well known, the concluding (and most extreme) track on Revolver was actually the first to be tackled when sessions began in April 1966. “Tomorrow Never Knows” drew its eerie lyric (“Lay down all thought, surrender to the void – it is shining”) from Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert’s book The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book Of The Dead – a much-discussed tome of the day which Lennon had picked up in London’s Indica bookshop in Mason’s Yard. (The bookshop in question, a beacon for London’s arty inner set, was also supported by Paul McCartney.)

Lennon’s desire to sound like “the Dalai Lama singing from the highest mountain top” inspired producer George Martin – a meticulous and ingenious facilitator – to route the vocal through a rotating Leslie speaker, normally used in tandem with Hammond organs. Lennon’s startling, otherworldly declamation consequently sat atop a forbidding edifice of super-compressed drums and chirruping, pinging tape loops, ridden on separate faders during the mix to form the track’s hallucinatory sound collage. In addition, a hard, bright, backward guitar solo bisects the track like ribbon lightning, while others entwine themselves around the mushily enticing somnolence of “I’m Only Sleeping.”

The Beatles’ first experiment with reversed tapes on the vocal coda to “Rain,” the B-side to the band’s “Paperback Writer” single, had been released two months previously. Lennon always claimed that the notion came about as he accidentally played the tape backwards on his Brenell recorder at home, but George Martin maintained that it was he who suggested applying the technique – an equally credible claim.

Clearly, the ingredients that would constitute psychedelia’s distinctive sonic vocabulary were now almost all in place. (Apart from phasing – but we’ll come to that.) In this, as with so much else, The Beatles’ seismic influence cannot be overestimated: where they led, a generation followed. The example they set – that pop music could accommodate all manner of sounds, shapes, and caprices – was exceptionally empowering: it threw open the gates to the playground and invited musicians to go figuratively (and sometimes, sadly, literally) nuts.

“Psychedelic music will color the whole popular music scene”

So, which fellow explorers were quickest out of the traps? The Byrds had laid down a formidable marker with the John Coltrane and jazz-indebted “Eight Miles High” in March 1966 – an appropriately lofty reverie which recounted the LA-based band’s August 1965 trip to London through a serenely sinister, heavy-lidded filter of magic realism. “You’ll find that it’s… stranger than known,” they sighed, over a keening tangle of 12-string Rickenbacker – and one could sense the doors of possibility swinging open. The adjectival “high”, of course, could be effortlessly interpreted as a not-so-covert code word for a herbally or chemically induced altered state; and the song was duly banned by several influential US radio stations. (Over the next few years, a similar fate would befall any number of records perceived to be peddling drug allusions.)

Also keenly aware of the prevailing swirls in the upper atmosphere were The Beach Boys. “Psychedelic music will cover the face of the world and color the whole popular music scene,” Brian Wilson enthused in a 1966 interview. “Anybody happening is psychedelic.” As ambassadors of universal love, brotherhood, and spiritual betterment, they were theoretically bang on trend with the tenets of “flower power” (psychedelia’s entry-level adjunct), while October 1966’s “Good Vibrations” deserves a seat at the very head of the table for the audacity of its multi-layered construction and its impressionistic shimmer alone. The Americana-encompassing SMiLE album project – which Wilson embarked upon after being introduced to erudite fellow songwriter Van Dyke Parks in early 1966 – promised to boldly broach a whole new series of frontiers.

Though the project was ultimately abandoned, a long-deferred happy ending came about when Wilson revisited SMiLE for a 2004 concert tour and studio album. Thirty-seven years earlier, however, fragments of the recording sessions found their way onto September 1967’s Smiley Smile. “Wind Chimes” and “Wonderful,” in particular, captured an openly psychedelic mood of rapt, childlike, time-suspended contemplation which chimed closely with the early output of Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett.

In search of higher consciousness

Among other pioneering psych adopters were Texas’ 13th Floor Elevators – raving garage-rockers in essence, but lent a philosophical mystique by the studiously earnest LSD evangelism of lyricist and electric jug player Tommy Hall. Their November 1966 debut album, The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators, couldn’t have nailed their freak flag to the mast any more overtly. Hall, by no means an acid dilettante, anonymously penned a provocative sleevenote which countenanced a “quest” towards a higher consciousness – and the churning, roiling “Fire Engine” contains a punning paean to the intensely hallucinogenic drug DMT (dimethyltryptamine). “Let me take you to the empty place in my fire engine,” yowls vocalist Roky Erickson… but, as Ben Graham notes in his book A Gathering Of Promises, “the way he phrases it, it’s clear that he’s actually singing, “Let me take you to DMT place.”

The Elevators’ unstinting acid regimen – actually taking to the stage tripping as a matter of principle – contributed in no small part to Erickson’s pitilessly swift mental decline. The Elevators even shocked the emblematic Grateful Dead, the key figures in San Francisco’s psychedelic scene, when they gigged in the city in August/September 1967. No mean acid crusaders themselves – guitarist Jerry Garcia was affectionately nicknamed Captain Trips – the Dead came to epitomize cosmic freedom for generations of festival-going, tie-dyed Deadheads, right into the 21st Century. From the Dead’s July 1968 second album, Anthem Of The Sun, “That’s It For The Other One” represents an exploratory peak, with instruments panning giddily back and forth across the stereo spectrum, and bluff electronic elements surfacing through the mix like monsters from the id.

The San Francisco scene

If the Dead personified a wantonly indulged alternative lifestyle, Jefferson Airplane were their closest San Franciscan cohorts in terms of counterculture heft. Their third album, November 1967’s After Bathing At Baxter’s, saw them engage most explicitly with the trappings of psychedelia (as on the musique concrète of “A Small Package Of Value Will Come To You, Shortly”), bearing as it did a title that equated to “after tripping on acid”. However, their June 1967 single “White Rabbit” – a Top 10 US hit – remains their most strikingly effective contribution to psych’s hall of infamy. Over a tense bolero rhythm, Grace Slick invoked the disquieting imagery of Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland to suggest the inquisitive pursuit of unknown pleasures – and, in the process, slipped pills, a hookah, and “some kind of mushroom” past the censors.

Honorable mentions should also be given to the Airplane’s less high-profile neighbors, Quicksilver Messenger Service and Country Joe & The Fish. Pealing exemplars of SF’s acid rock guitar sound, Quicksilver’s John Cipollina and Gary Duncan boasted a finely honed precision which contrasted with the Dead’s more organic, open-ended improvisations. Their disciplined interplay is demonstrated to dramatic, transcendent effect on “The Fool,” the 12-minute showpiece of their self-titled May 1968 debut album, streaked with controlled feedback contrails.

Country Joe & The Fish, meanwhile, based in Berkeley, on the other side of the Bay Bridge, were driven by the politicized conscience of songwriter Country Joe McDonald. More a subversive, unruly protest group than a streamlined rock entity, they nevertheless set forth for psychedelia’s foggiest shores with the likes of “Bass Strings,” from 1967’s Electric Music For The Mind And Body, lit only by a thin corona of organ.

The above-mentioned bands were only the tip of a colossal West Coast iceberg, of course, with Moby Grape, Janis Joplin and Big Brother & The Holding Company, and The Sons Of Champlin particularly deserving of further investigation. And, before leaving the Bay Area, Fifty Foot Hose warrant a gold star (or a death star) for the unnerving, avant-garde title track of 1967’s Cauldron album – not one to be listened to in the dark, or alone.

This outpouring of exciting new music was facilitated by a proliferation of amenably hip venues, notably the Avalon Ballroom, Fillmore West, and Matrix, and counterculture “tribal gatherings” such as the Trips Festival – a January 1966 bacchanal co-devised by the renegade author, Merry Prankster and folk devil, Ken Kesey. (Kesey’s exploits are immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s seminal 1968 book, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.) These gatherings would, of course, set the stage for massive events later on like the Monterey Pop Festival and the Woodstock Festival. Also of crucial importance were FM radio stations such as the groundbreaking KMPX, KSAN-FM and KPPC. Unafraid to include new-era long-form songs on the playlist, these stations simultaneously fed into and reflected the generational tipping point, circa 1968, wherein albums started to outsell singles for the first time.

LA takes over

Nearly 400 miles south, Los Angeles had its own burgeoning music scene – one capable of accommodating the psychedelic soul of The Chamber Brothers (whose “Time Has Come Today” nearly cracked the US Top 10 in December 1967), the fitful brilliance of the ill-assorted West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band (“I Won’t Hurt You” from Part One being a faintly creepy, low-glowing highlight) and the opportunistic psych-lite of the exuberantly overdressed Strawberry Alarm Clock, paisley-bedecked human soft furnishings whose “Incense And Peppermints” went all the way to No.1 in May 1967.

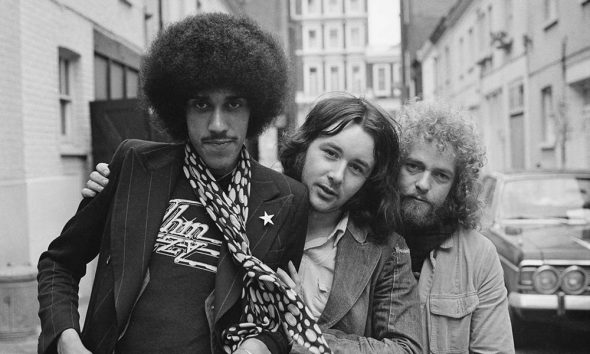

Two of LA’s most original acts, however, only skirted psychedelia by default. Love, the well-ahead-of-the-curve multiracial ensemble fronted by the redoubtable Arthur Lee, may have sported a modishly bendy logo and cover art on 1968’s unimpeachable Forever Changes – but in its gentle, troubled introspection, the album was already looking over the next hill. “The Good Humor Man He Sees Everything Like This” does at least constitute an interlude of experiential wonder (“Hummingbirds hum, why do they hum?”), and even features a token wrap of tape manipulation as the track ends.

Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band, meanwhile, were already well on the way to reconfiguring the psychogeography of gutbucket R&B, convincingly elevating it to a boundary-breaching Dadaist realm. When producer Bob Krasnow applied then state-of-the-art studio effects to Beefheart’s October 1968 second album, Strictly Personal (ie, the backward cymbal and treated vocal on “Beatle Bones’n’Smokin” Stones’), an initially acquiescent Beefheart quickly went on record to decry what he saw as an unnecessary, gimmicky dressing-up of music that was sufficiently edgy in its own right. (Nevertheless, many listeners are just fine with those gimmicks.)

Phasing and the studio as an instrument

Among the effects in question was phasing, arguably psychedelia’s single most obvious identifier – and, for once, The Beatles were only indirectly responsible. While holed up in London’s Olympic Studios in June 1967 to record the backing track for “All You Need Is Love,” their producer George Martin asked for “ADT” (automatic or artificial double-tracking, a technique originated at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios) to be placed on Lennon’s vocal. Unable to comply because Olympic’s tape machines operated differently to EMI’s, tape operator George Chkiantz pledged to devise his own outlandish tape effect – and came up with the sense-warping, harmonic frequency sweep which became known as phasing or flanging.

Olympic pressed phasing into swimmy service almost immediately on The Small Faces’ August 1967 single “Itchycoo Park” – a larkish, high-summer, Top 3 hit from the freshly acid-initiated flower mods whose round-sleeved 1968 album, Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake, also included phased drumming on its instrumental title track. Olympic Studios subsequently hosted The Jimi Hendrix Experience, fronted by the envelope-pushing guitarist who, more than anyone, became psychedelia’s most aurally and visually flamboyant avatar. “Bold As Love’, from the band’s December 1967 second album, Axis: Bold As Love, has a scorching corkscrew of phasing applied to its outro – while “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be),” from the Experience’s October 1968 double-album Electric Ladyland, is a lucid, fully realized, mixing-desk-as-paintbox triumph.

Oddly enough, The Beatles themselves only ever deployed phasing on Magical Mystery Tour’s entranced “Blue Jay Way” (apart from a fascinating, accidental pre-echo of the effect on the drum fill six seconds into 1963’s “From Me To You”). Their brief psych chapter nevertheless took in such indomitable glories as “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds,” and “It’s All Too Much,” so their pre-eminence in the pantheon is inarguable.

Another accident of timing? The introduction of the wah-wah pedal in the middle of the 1960s. Or, as its patent read, the “foot controlled continuously variable preference circuit for musical instruments.” Originally imagined as a cool effect for saxophones, it became a standard psychedelic tool for electric guitars.

Psychedelic makeovers

If Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Procol Harum’s magisterial “A Whiter Shade Of Pale” formed the twin pillars of 1967’s so-called Summer Of Love, The Beatles’ long-standing rivals, The Rolling Stones, appeared to be slightly on the back foot. In relation to their December 1967 album Their Satanic Majesties Request, drummer Charlie Watts’ mother is said to have mordantly remarked that they were “at least two weeks ahead of their time” – yet its sepulchral, decadent atmosphere has lasted admirably down the years. The clangorous “Citadel” is enveloped in a whirling, sexy miasma, while the apocalyptic August 1967 single “We Love You” blows a leering, ironic kiss towards the forces of law and order in the wake of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards’ arrests on drug charges earlier in the year.

During the short period when a psychedelic makeover was an essential sartorial and cultural statement, the blues-rock supergroup Cream unleashed Martin Sharp’s Day-Glo sleeve to Disraeli Gears, while guitarist Eric Clapton saw fit to append a raga-tinged solo to the yearning “Dance The Night Away.” The Ingoes, meanwhile, were renamed Blossom Toes at the behest of manager Giorgio Gomelsky, decked out in paisley finery and installed in a house in Fulham until they could write some voguish material. The uncanny “Look At Me I’m You,” from their debut album We Are Ever So Clean, ranks alongside anything from the era.

In Britain’s singles racks, you couldn’t move for psych-pop pearls. Inscrutable one-offs such as Tintern Abbey’s haunted “Beeside” vied for space with “Defecting Grey,” a compellingly wayward construction by the rejuvenated Pretty Things. The tightly processed “Imposters Of Life’s Magazine” by Jeff Lynne’s Idle Race nestled alongside the urgent “My White Bicycle” by Tomorrow (featuring future Yes guitarist Steve Howe), while Traffic’s contentiously blissed-out “Hole In My Shoe,” became a UK No.2 hit in August 1967.

Kudos also to those who just missed the bus – not least July, whose self-titled 1968 album included the elliptical “Dandelion Seeds’, and The End, produced by Stones bassist Bill Wyman, whose wonderfully soft-centered album Introspection was recorded in early 1968 but not released until November 1969.

London’s psychedelic underground

The toast of London’s psychedelic pop underground were Pink Floyd: wilful experimentalists whose audio-visual ambition, not to mention their spectacular incongruity where the conventional touring doctrine was concerned, anticipated the festivals and dedicated concert events that proliferated in the following decade. Their light shows at the famed UFO Club were the stuff of legend. With the precociously talented Syd Barrett at the helm, Pink Floyd produced psychedelia’s most matchless, concise Top 5 snapshot, “See Emily Play,” while their mysterious August 1967 debut album, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, showcased Barrett’s uniquely charming, childlike muse (“Matilda Mother,” “The Gnome,” “The Scarecrow”).

Tragically, Barrett’s psyche unraveled with distressing rapidity, his prodigious LSD intake the major (if not sole) factor, and by April 1968 his place in the band had been taken by David Gilmour. The Mk II Floyd ostensibly blazed a trail for progressive rock with their penchant for extended pieces and commensurately lengthy live performances, but it was a member of Canterbury Scene godheads Soft Machine – Pink Floyd’s regular accomplices in London’s underground clubs – who carried the flame for psychedelia into the 70s and well beyond.

Daevid Allen, Soft Machine’s original guitarist, formed his next band, Gong, in France, and steadfastly constructed a jocularly intricate mythology around the band itself and its spiritually inquisitive repertoire. The “Radio Gnome Invisible” trilogy – 1973’s Flying Teapot and Angels Egg, and 1974’s You – accordingly bubbles with mischievous, seditious lyrics, giggles, shrieks, and some titanic playing. From the latter album, “Master Builder” is a typically heady and fervid Gong assemblage, a third-eye projection pinballing between the planets.

Psych in the modern era

Thereafter, various noble bodies kept psych’s antic spirit alive in the 80s and 90s. The largely LA-based “Paisley Underground,” for instance, saw bands such as The Rain Parade, The Three O’Clock, and Green On Red flirting heavily with psychedelic tones and textures. In the UK, XTC embarked on a psych side-trip as The Dukes Of Stratosphear, and delivered such an inspired, pitch-perfect homage that their output (as compiled on Chips From The Chocolate Fireball) outstripped the heroes they sought to salute. In a broadly similar vein, The Godfathers tipped their hats towards The Creation’s abyssal “How Does It Feel To Feel” (the US mix, specifically) on 1988’s “When Am I Coming Down” – the same year that the nominal Second Summer Of Love began in the UK, fuelled by acid house and the fledgling rave culture.

Today, psychedelia is in eminently safe hands. There are plenty of non-rock genres that psychedelic music has infiltrated. Electronic music, of course, with its psychedelic trance sub-genre. Psychedelic folk saw a revival with the so-called freak folk genre, led by folks such as Devendra Banhart and Joanna Newsom. Hip-hop even had a moment with De La Soul’s D.A.I.S.Y. Age.

Oklahoma’s Flaming Lips continue to plough a distinctly humanistic, existential, strobe-lit psych furrow; Australia’s Tame Impala sit on a beautiful event horizon permanently illuminated by the after-image of “I Am The Walrus”; Ty Seagall fearlessly stares down the swarming acid horrors that bedevil psych’s dark underbelly – and a coterie of believers, including The Coral and Jane Weaver, prove, time and again, that there’s still limitless scope in the well-starred union of psychedelia and pop. Long may that be so.

Looking for more? Discover the Best Psychedelic Albums: 30 Essential Records To Expand Your Mind.