Pierre Henry: The Avant-Garde Composer Who Shaped Rock’s Future

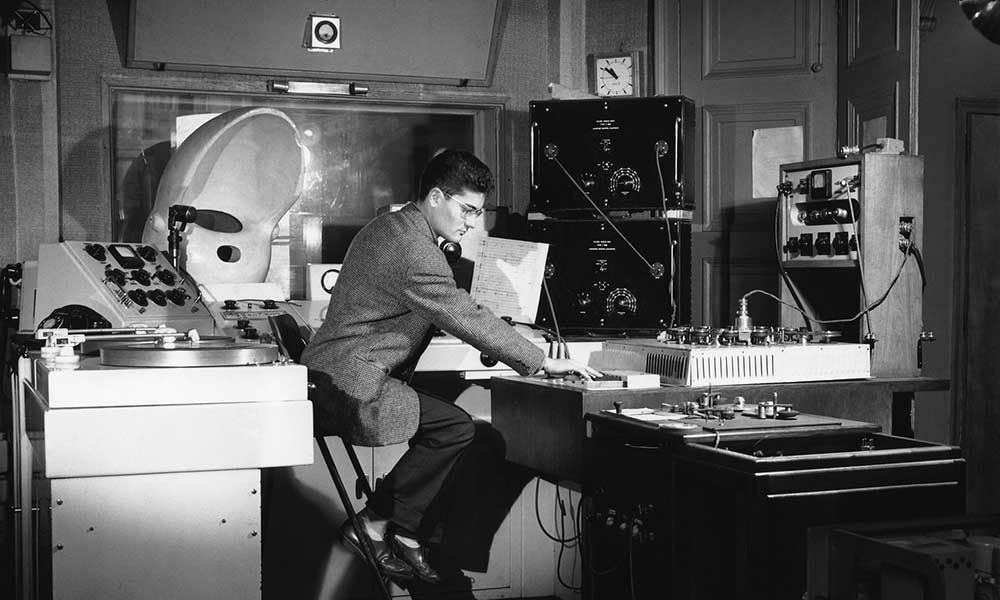

After declaring, in 1947, that it was necessary to destroy music, avant-garde composer Pierre Henry built a body of work that pointed to the future.

A word to the wise: should you ever be asked, in the course of your next pub quiz, which young revolutionary was responsible for proclaiming, “It is necessary to destroy music,” your mind might reflexively scroll through a Rolodex of iconoclasts and provocateurs including the likes of John Lydon, Frank Zappa, Thurston Moore, Conrad Schnitzler, and Brian Eno. Credible guesses all; but these words were in fact expressed by Pierre Henry, a trailblazer in the sound-sourcing and -manipulating principles of musique concrète, in a short, pugnacious essay entitled For Thinking About New Music, which the composer, who was born on December 9, 1927, wrote in 1947, when he was just 20.

“Today, music can have only one [meaning] in relation to cries, laughter, sex, death,” Henry continued. “I believe that the [tape] recorder is currently the best instrument for the composer who really wants to create by ear for the ear.”

Pierre Henry, who died on July 4, 2017, aged 89, has long been acknowledged as a key figure in the development of electroacoustic and electronic music. Here was a galvanic and liberating presence whose tireless experimentation, immersed throughout in an unbounded world of sonic potentialities, manifested itself as a lifetime’s worth of challenging, fearless and redemptive works. His storied career is definitively saluted with Polyphonies, a 12CD compilation curated and remastered by the composer himself, and including nine previously unreleased pieces.

Listen to Polyphonies on Apple Music and Spotify.

While Henry’s reputation is unassailable among aficionados of experimental music, many rock and pop fans tend to know little or nothing about the man. Some may be aware of his controversial 1969 collaboration with Spooky Tooth, on the album Ceremony (included herein), while others might appreciate the titanic shadow his “Psyché Rock” 7” (1967, with Michel Colombier) casts over the theme from Futurama; but this collection should help to broaden the perception of Pierre Henry as a found-sound avatar whose inquisitive facility with tape recorders, mixing desks and repurposed instrumentation pre-empted entire swathes of psychedelia, electro, and remix culture.

Interestingly, with occasional digressions that see adjacent newer and older pieces complement or contrast with each other, the chronology generally runs in reverse across Polyphonies’ 12 CDs. Therefore, the set effectively begins with Henry’s 2016 work, Chroniques Terriennes, and concludes with formative outings from 1950 – Musique Sans Titre, Concerto Des Ambiguïtés and Symphonie Pour Un Homme Seul, the latter assembled with fellow musique concrète pioneer Pierre Schaeffer. The effect is to double-underline one’s respect for Pierre Henry: as the pieces recede through the decades, the composer’s boldly singular vision becomes more and more admirable.

That said, the previously unreleased Chronique Terriennes makes for an absorbing entry point – 12 sequences described by the composer as “… day by day chronicles of encounters with the instrument, nature and the essence of music.” Tranquil and discreetly sinister by turns, this remarkable soundscape achieves a peculiar internal logic by juxtaposing the spacious reverb of ships’ horns carried across a large body of water; birdsong; a short burst of sprechgesang; a creaking door; and the chirping of crickets which gradually becomes dense and oppressive. In its textural rummaging and scurrying, it’s the audio equivalent of Jan Švankmajer’s unsettling stop-frame animations.

For a compilation that celebrates a body of ostensibly abstract work, Polyphonies contains some surprisingly illustrative interludes. The implicit narrative arc of Une Tour De Babel (1998), for instance, appropriately maps out awe, hubris and, ultimately, confusion, while the previous year’s Une Histoire Naturelle Ou Les Roues De La Terre combines the elemental with the mechanistic to depict man’s injuriously cavalier relationship with the animals and ecosystems of a “globe in perdition.”

Some pieces, on the other hand, can be appreciated on a more basic level, should listeners wish to park their intellect for a spell. The twittering, peeping electronics and vertiginous sine waves of 1973’s Kyldex – unissued excerpts from a three-and-a-half-hour “cybernetic opera” – are manna for lovers of early polyphonic synths; or, indeed, anyone for whom the Clangers moonscape exerts a powerfully nostalgic gravity of its own.

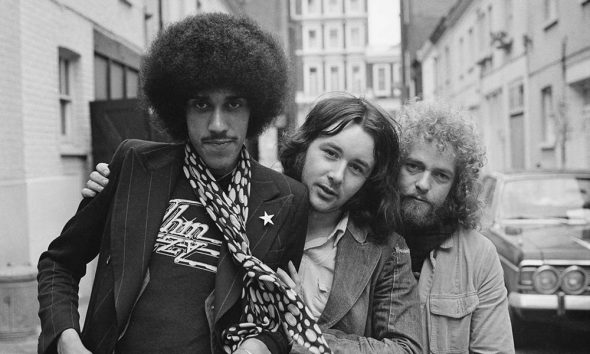

Similarly, curious beginners coming at Polyphonies from a rock or pop background are directed towards Rock Électronique – obliquely echoed quasar pulses from 1963, the year of Merseybeat in the UK – and, of course, Ceremony, Henry’s 1969 “electronic mass” in collaboration with Spooky Tooth. The latter experiment bewildered and alienated the bulk of the band’s fanbase at the time, but it now sounds quite unlike anything else attempted by any group at any point in history. Perversely – brilliantly – the band’s blues-rock song beds are ducked in the mix way beneath Henry’s bilious, shifting overlay of storm-tossed electronics. “Credo” represents the line in the sand, with Henry contributing a looped, nonsensical, cut-up vocal that comes at the listener as relentlessly as wasps at a picnic site. Say what you will, but it takes genius to interpret rock music in such a wilfully opaque manner.

The real kicker is that works such as Voile d’Orphée, Spatiodynamisme, Astrologie (all dating from 1953) and 1950’s Symphonie Pour Un Homme Seul still retain their power to shock, confound and delight. These arresting sonic creations are destined to remain unmoored from time: permanently inspirational, barrier-breaching pieces that, despite the rigorous scholastics that went into their construction, seem to reaffirm the message that the shackles are off, and everything is possible.

KIRBY

April 29, 2023 at 7:51 am

Without PIERRE HENRY there would not have been Musique Concrett although Varese who came shortly after would have come close. Rock “electronic” comes nowhere close.