Deutsche Courage: The Boundary-Breaking Minds Behind Experimental German Music

Out on a limb and working in isolation, the finest minds behind experimental German music in the 60s and 70s left a world-changing legacy.

Thanks in large part to Kraftwerk’s weighty influence on synth-pop, hip-hop, and subsequent strains of dance music, German music has long since overturned the preconceptions that initially (and insultingly) went with the territory. Nevertheless, in certain quarters there is still a bewildering inclination to lump it all together. The common ground between, say, Scorpions and Faust is negligible at best, but the despised appellation “krautrock” did little to encourage the expectation of stylistic diversity. (Faust, cheeringly, up-ended the term with their sarcastically monomaniacal “Krautrock,” from the 1973 album Faust IV.)

It’s perhaps fairest to suggest that the minds behind the most experimental German music in the transitional period between 1967 and 1976 shared a commonality of purpose. Out on a limb, and largely working in isolation from each other, they were nevertheless unified by a compulsion to forge ahead, to experiment with modes and means of expression, and consequently to establish an entirely new milieu. In so doing, they were tacitly seceding from the American and British rock, pop and soul archetypes that had previously held sway.

That said, there were certain British and American totems whose influence fed directly into the development of Germany’s new music. Pink Floyd’s solemn galactic bleeps echoed right across the kosmische firmament; Jimi Hendrix’s sonic boldness heralded revolution, even if his scorching flamboyance found little purchase in the broader context of drone-based minimalism; and Frank Zappa’s subversive cynicism chimed with then-prevalent student insurrection – much to his distaste.

Amon Düül

Tellingly, appearing alongside Frank Zappa & The Mothers Of Invention at the Internationale Essener Songtage festival in Essen, in September 1968, were three pivotal new German bands who pointed towards the future of German music: Amon Düül, Tangerine Dream and Guru Guru. The first of these were a loose collective, living communally in a house in Munich and intermittently flailing away at instruments. Their fitful, floating line-up included relatively accomplished players and some decidedly less competent accompanists whose presence represented a political or artistic gesture: as a result, the group unavoidably split into factions.

Their schismatic appearance in Essen resulted in the breakaway formation of the ostensibly more musical Amon Düül II, led by guitarist Chris Karrer. If the cheerfully wayward, doggedly percussive jams on the original Amon Düül’s Psychedelic Underground (1969), Collapsing Singvögel Rückwärts & Co (1969), and Disaster (1972), all drawn from the same 1968 sessions, indicate a willfully anarchic intent, 1971’s Paradieswarts Düül is a comparatively beatific acid-folk interlude (especially the 17-minute “Love Is Peace”).

Meanwhile, Amon Düül II’s first three albums – Phallus Dei (1969), Yeti (1970) and Tanz Der Lemminge (1971) – are vivid, belligerent entities. Yeti in particular is a raucous gem of its kind – “Eye Shaking King,” “Archangel Thunderbird,” and “Soap Shop Rock” are tough, strange and entranced.

Guru Guru

As with Amon Düül II, Guru Guru made a liberating sound that was marginally recognizable as rock, albeit given to plunging deliriously into sinkholes of noise. With drummer Mani Neumeier as their figurehead, Guru Guru lived communally and engaged wholeheartedly with the radical polemic of the times. Explicitly politicized (and often tripping), they powerfully convey the essence of gleeful disorder on their 1971 debut album, UFO, and 1972’s Känguru.

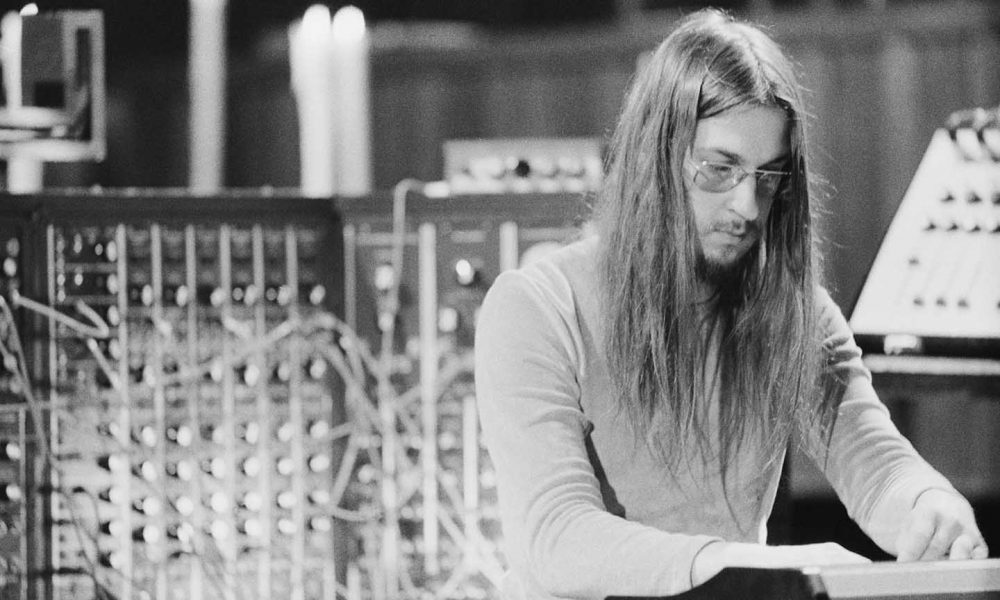

Tangerine Dream

As for Tangerine Dream, their enduring influence on trance music (and, as a side effect, the New Age movement) is inarguable, but their early albums come from a deeper and darker strain of German music than is often remembered. Formed by Edgar Froese in 1967, the initial line-up (featuring Froese, drummer Klaus Schulze and the extraordinary anti-musician Conrad Schnitzler, armed with a cello and typewriter) pursued a determinedly free-form furrow in the hothouse environs of the Zodiak Free Arts Lab in Berlin, but it wasn’t until the latter two left and were replaced by Peter Baumann and Christopher Franke that Tangerine Dream entered their nominally “classic” synth-trio phase. 1974’s game-changing Phaedra, released under the terms of their then-new contract with Virgin Records, battles with 1972’s Zeit to be crowned their ultimate masterpiece, the latter methodically portraying the space-time continuum as not only awe-inspiring, but also lonely, terrifying and inert.

Klaus Schulze and Conrad Schnitzler

Former members Schulze and Schnitzler also continued to push the boundaries. After initially decamping to Ash Ra Tempel, Schulze embarked upon a lengthy and prolific solo career, beginning with the primal, supremely twisted electronic manipulation of Irrlicht (1972). Schnitzler, meanwhile, remained true to his avant-garde principles on a dizzying array of chaotic and confrontational limited edition releases over the following years – not least 1973’s Rot, which (like Faust IV) contained a sonically adversarial 20-minute track called “Krautrock.”

Schnitzler was also responsible for co-birthing Kluster with fellow Zodiak Free Arts Lab founder Hans-Joachim Roedelius and an attendee called Dieter Moebius. This trio released three wholly improvised abstract albums (Zwei-Osterei, Klopfzeichen and Eruption, the first two appearing, surreally, on Schwann, a Christian label) before Roedelius and Moebius parted ways with Schnitzler and became Cluster – a softer name for what eventually became a softer sound among the sometimes abrasive noises coming out of the German music scene in the early 70s. If 1971’s Cluster and the following year’s Cluster II thrillingly took electronic sound as far into a hostile wilderness as seemed conceivable, 1974’s Zuckerzeit radiated a melodious, goofy, proto-synth-pop contentment, indicative of the duo’s tranquil living circumstances in a community in the village of Forst, Lower Saxony.

NEU! and Harmonia

In 1973, a significant visitor to the community – by now the epicenter of much of the most forward-thinking German music of the early 70s – was guitarist Michael Rother, at that point one half of NEU! with drummer/firebrand Klaus Dinger. Both former members of Kraftwerk, Rother and Dinger were unsustainably polarized as personalities – the former serene and measured, the latter impulsive and extrovert – but the combination made for some enticingly unresolved, hypnotically repetitive music over the course of their three albums (NEU!, NEU! II and NEU! ’75). Dinger’s relentless “motorik” beat was described instead by its architect as “endlose gerade, like driving down a long road or lane.”

Upon arrival at Forst, Rother began a collaboration with Moebius and Roedelius under the name of Harmonia. If Musik Von Harmonia (1974) was an absorbing, randomly-generated guitar-meets-electronica snapshot, the following year’s Deluxe beamed forth a dignified, magisterial, synth-pop sensibility. One further album, Tracks & Traces, was recorded with an enraptured Brian Eno in 1976, and released in 1997 under the name of Harmonia 76. (Dinger, for his part, moved center-stage and formed the attractively sleek and giddy La Düsseldorf in 1975, with his brother Thomas on drums and Hans Lampe on electronics.)

Kraftwerk

It seems unthinkable to contrast the formalized Kraftwerk brand identity everyone now knows and adores with the casual, revolving-door nature of the band’s personnel when Rother and Dinger were briefly on board. The Echoplex flute eddies and comparatively primitive electronics of Kraftwerk (1970), Kraftwerk 2 (1972) and Ralf Und Florian (1973) give little indication of the stylized perfection that would emerge with 1974’s Autobahn – the placid, streamlined title track of which brought German music to the wider world when it became a Top 30 hit in the US and almost brushed the Top 10 in Britain.

Successive generations may never fully grasp the shock value of Kraftwerk’s sound and appearance at that time: founder members Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, joined by newbies Karl Bartos and Wolfgang Flür, eschewed guitars and drums altogether to present an all-electronic front line. Short-haired and dressed as if for work, their image was an exhilarating affront to rock orthodoxy, while their romanticized embrace of technology was subtly underwritten with a steely pragmatism and an indefinable sense of longing. Radio-Activity (1975), Trans-Europe Express (1977) and The Man Machine (1978) further refined their deportment and sonics, with the middle album representing an ideological pinnacle: “Europe Endless,” a dreamily benign, existential love letter, has now acquired a layer of meaning scarcely conceivable at the time of recording.

Kraftwerk will always duke it out with Can as the most forward-thinking purveyors of German experimental music with the longest reach. Formed in Cologne in 1968, Can’s intensely rhythmic base implied a kinship with the hard funk of James Brown, but intuitively unusual musicianship and inspired mixing decisions made them a paragon of otherness. The double-album Tago Mago (1971) presents them at their most immersed and transported – Side One (“Paperhouse,” “Mushroom,” and “Oh Yeah”) casts a stone into a still-unattainable future – but the whispering, levitational Ege Bamyasi (1972) and Future Days (1973) also remain curiously ageless and inimitable, however much their influence informs the entire ethos of post-rock.

Faust

Faust were mentioned at the top of this piece, so it seems only fair to conclude it with a salute to this uniquely subversive ensemble, fondly indulged by the Polydor label until the true nature of their heedlessly uncommercial “repertoire” became apparent. Their self-titled 1971 debut album, arrestingly pressed on clear vinyl and housed in a transparent “X-ray” sleeve, was a disquieting mélange of found and manipulated sounds, grimy jamming, bleakly refracted humor and livid electronics. The follow-up, 1972’s So Far, paid exquisitely ironic lip service to the notion of conventional song forms (“It’s A Rainy Day, Sunshine Girl,” “… In The Spirit”), but was still palpably the work of an ungovernable force that naturally gravitated to the outer edges.