Back Into The Labyrinth: Sting’s Foray Into Classical Music

In an artistic about-turn that no one predicted, Sting confidently explored classical music across three albums that remain some of his most experimental.

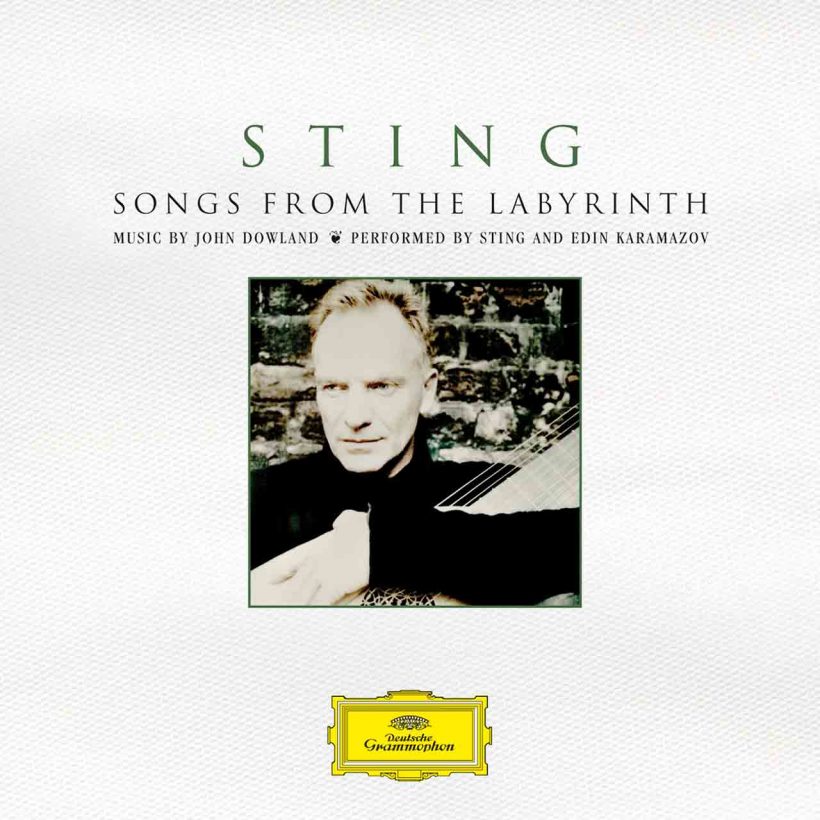

Sting’s first album of the new millennium, 2003’s Sacred Love, proved that he could firmly stake his claim on the new musical landscape of the 21st Century. Confident, beat-driven songs aided and abetted by electronic producer Kipper, the album seemed to firmly point towards the future. That “future,” however, turned out to be vastly different than anything fans might have expected. When Songs From The Labyrinth emerged in 2006 it certainly found Sting pushing himself like never before, but also saw him looking back – to classical music, the 16th Century, and a period which, some scholars argue, saw the birth of pop music.

The man who had merged reggae with punk, and jazz with world music, now embraced madrigals penned by composer and lutenist John Dowland. This time out, Sting swapped the large, genre-straddling ensembles for a more modest musical palette: Bosnian lutenist Edin Karamazov and the singer’s own multi-tracked vocals, stacked together at times to form a chorale. The results were, as Rolling Stone noted at the time, “nostalgic music that sounds exquisitely weathered,” in which Sting found “timeliness” in the original songs, investing them “with skill and soul.”

Further illustrating Sting’s connection with the music was his decision to interpolate readings from Dowland’s letters into the album. In Rolling Stone’s estimation, this recast Dowling “as a Renaissance Nick Drake, a tortured dude who transcends personal agony with sublime composition.” It was an apt observation, given that Sting himself had so openly addressed his own tragedies on record – most notably on his third solo album, 1991’s The Soul Cages, on which he dealt with the loss of his father.

If Dowland’s madrigals were, essentially, the first pop songs (if you take “pop” to mean “popular,” then certainly they were the hits of his day), it’s easy to see Sting identifying with a creative spirit who truly raised the bar. Arguably a creative gamble on Sting’s part, Songs From The Labyrinth was released on October 10, 2006, and strode confidently to No.24 in the UK and No.25 in the US – no small feat for a classical album released on the Deutsche Grammophon imprint at a time when the charts were dominated by the likes of Sean Paul, Beyoncé, and Justin Timberlake.

Never one to do things by halves, Sting, having hit upon a new creative path, continued to follow it for his next outing, 2009’s If On A Winter’s Night… Released on October 21st of that year, the album also followed a brief reunion with The Police – a period which perhaps reminded Sting of the artistic strides he’d made when first embarking on a solo career. For his second Deutsche Grammophon release, he put together a 42-piece orchestra that included classical instrumentation, folk musicians, and doyens from his much-loved jazz world, among them percussionist Cyro Baptista, Miles Davis alumni Jack DeJohnette (drums), and Kenny Garrett (saxophone).

The material, too, came from a wider range of sources than before: carols originally sung in the German and Basque languages ( “Lo, How A Rose E’er Blooming,” “Gabriel’s Message’), 18th-century children’s songs ( “Soul Cake”), 17th-century compositions from Henry Purcell, and even a song his of own, a classical reworking of “The Hounds Of Winter,” which originally opened 1996’s Mercury Falling.

Patently, you could trust Sting to look further than the closest Christmas songbook. As he said himself at the time, “The theme of winter is rich in inspiration and material,” and he was “filtering all these disparate styles into one album.” The results matched his most ambitious work to date, and set him up for his next move.

Barely pausing for breath, Symphonicities emerged on July 13, 2010, a mere nine months after If On A Winter’s Night…, and brought its creator full circle. As if it were the most natural thing in the world, highlights from both The Police and Sting’s solo releases were rearranged for classical performance by some of the finest orchestras in the world, among them touring partners The Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, making for one of Sting’s most invigorating efforts yet.

As Rolling Stone noted, the album “rocks hard from the outset,” as “Next To You,” the opening cut from The Police’s debut album, Outlandos D’Amour, races from the traps, the original’s propulsive drumming and angular guitars replaced by satisfyingly frenetic strings. Equally propulsive is “She’s Too Good For Me,” a song which originally appeared on Ten Summoner’s Tales, and, as it did on that album, offers some levity to proceedings. Elsewhere, some of Sting’s solo material seemed tailor-made for the orchestral treatment, including an exquisitely rendered “Englishman In New York” and a haunting “We Work The Black Seam.”

While offering new perspectives on old classics, Symphonicities also helped Sting’s music find new audiences. The Police classic “Roxanne” had been unforgettably reimagined as a tango number in Baz Luhrmann’s cult 2001 film Moulin Rouge!, and the version on Symphonicities – along with the new arrangement of “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” – seemed tailor-made for ballrooms around the world.

“Sting has shown he’s a rocker who knows how to scale up” was how Rolling Stone concluded their review. They weren’t wrong. The theatricality inherent in all three of these albums put him in good stead for 2013’s The Last Ship, a companion release to his 2014 stage play of the same name.

And yet Sting keeps on changing. 2016 saw the release of 57th & 9th, hailed as his first pop/rock album in 13 years. It proved that, whether he’s scaling up or stripping back, Sting has never failed to deliver. The results have been one of the most compelling bodies of work any artist has amassed.