If You like Curtis Mayfield… You’ll Love Kendrick Lamar

Unafraid to tackle the big subjects, artists like Curtis Mayfield and Kendrick Lamar are as brave in their music as they are in their politics.

Curtis Mayfield was never content with his lot as a mere singer. For him the entertainment business offered the opportunity to say something deeper, more meaningful; to cast a light on the problems of the world, and the Afro-American community in particular, through the medium of soul music.

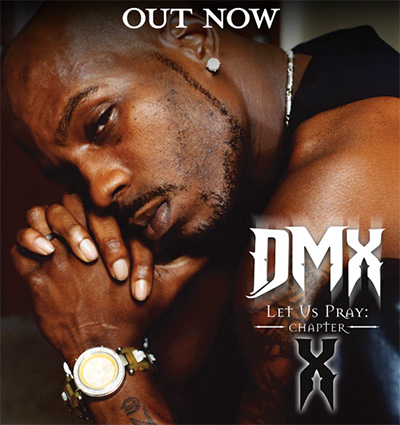

Forty years may separate the 70s and 2010s, but many of the same problems remain. Fortunately, we are still blessed with artists willing to raise their head above the parapet, and Kendrick Lamar has established himself as a Curtis Mayfield for his generation. His politically charged songs, utilising soul music’s natural successor, hip-hop, have cast a potent light on the dilemmas and difficulties currently facing America’s black community.

Mayfield was among the first performers to address black pride and community struggle in his music, and his songs became civil-rights anthems. Similarly, Lamar has been at the epicentre of the Black Lives Matter movement, with his works adopted as anthems on protest marches, and his messages taught in American schools. Yet while both performers have tackled racial injustices head on, they have also insisted on a path of hope. There are some powerful mirrored images within both men’s lyrics. For Curtis Mayfield’s ‘Move On Up’, with its pleas for racial togetherness and high-minded response to endemic racism, read Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Alright’: a positivist call for black unity that has been adopted by police-brutality protesters who chant its chorus as an anthem.

As bold in their creativity as in their politics, both artists seized creative control of their work from an early stage, deploying auteur-like propensities as they pushed the boundaries of their respective genres. As a member of The Impressions, Mayfield broke the mould for soul singers by writing his own material at a time when it was virtually unknown for a young black artist to do so. Employing influences from the gospel music of his youth, alongside Latin rhythms and punchy horn blasts, he helped develop the Chicago soul sound during his time as producer at OKeh Records. Later, on his solo masterpieces, Mayfield expanded the parameters of the genre by adding potent measures of psychedelic rock and funk to the mix. He broke the mould thematically too, by including songs about racial pride and civic responsibility on his 1970 debut album, Curtis, developing the theme yet further on his socially conscious 1971 sophomore effort, Roots.

For a man still in the relative infancy of his career, Kendrick Lamar has been no creative slouch, either. Earning critical plaudits and huge popularity in equal measure, his first two albums, 2011’s Section.80 and the following year’s Good Kid, MAAD City, traded on a hugely varied, soulful mix of hip-hop and trap styles. Making a firm creative shift on the 2015 follow-up, To Pimp A Butterfly, Lamar employed a hand-picked team of producers and musicians to produce a potent, organic mix of funk, soul and jazz that rejuvenated both the hip-hop and jazz scenes in its wake.

Like Mayfield, Lamar has continually pushed the thematic boat. Good Kid, MAAD City was an autobiographical concept album that upended the Compton gangsta rap rulebook to weave a documentary-style story of family and ghetto life, told from the perspective of a “good kid” from a loving, Christian family. To Pimp A Butterfly proved an album of even greater lyrical depth, with Lamar casting himself as the focal point of a series of vignettes, bookended by slices of a poem, that document his struggles with the trappings of fame, the love for his home city, and his thoughts on race and the experience of being black in America.

Despite the obvious stylistic differences between their respective genres, Mayfield and Lamar’s music also share much common ground. Not for nothing did the latter choose to sample the former’s ‘Kung Fu’ (a track from Mayfield’s 1974 album Sweet Exorcist) for his single ‘King Kunta’. However, Mayfield’s music aligns closest in spirit and sound to Lamar on his third album, 1972’s Superfly. The work was composed as a soundtrack to the Blaxpoitation film of the same name, and added a harder, funkier, edge to his music. Meanwhile, the lyrics, which echoed the gangster-fied, street-tough sentiments of the film, with its portrayal of drug deals and ghetto shootings, astutely managed to avoid either glorification or moralising on the pimp protagonist’s story.

For Lamar’s part, his music has always been cinematic in scope, from the linear narrative and highly visual images conjured up on Good Kid, MAAD City, to the non-linear and poetic, but no less visual, concerns of To Pimp A Butterfly. Both artists share a mutual love for the soulful groove, but it’s with the funk genre that they have shared the most explicit common ground. Echoing Superfly’s stridently funky grooves, with To Pimp A Butterfly Lamar had the genre locked down hard, with the cosmic slop of album opener ‘Wesley’s Theory’ even featuring the hallowed presence of P-Funk overlord George Clinton.

Balancing a patina of cool and cultural relevance while also straddling the pop charts, the world needs artists like Curtis Mayfield and Kendrick Lamar, as brave in their music as they are in their politics.

Listen to the best of Kendrick Lamar on Apple Music and Spotify.