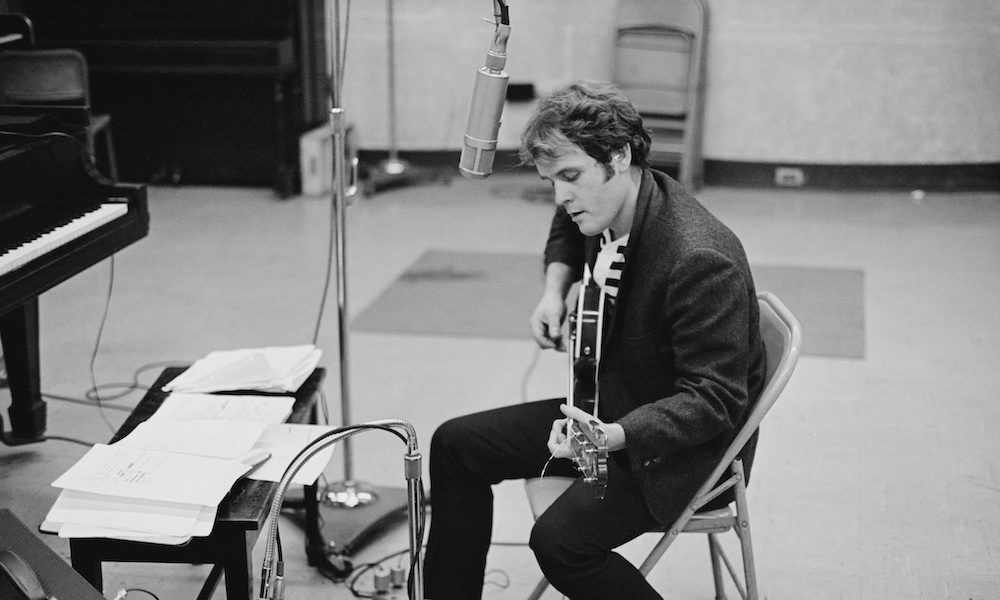

Reason To Believe: The Introspective Brilliance Of Tim Hardin

Endlessly underrated, Hardin wrote some of the most beautiful and enduring songs of his day, including the much-covered ‘If I Were A Carpenter’ and ‘Reason To Believe.’

As with a number of his contemporaries of the mid-to-late 1960s, you won’t get much of an impression of the importance of Tim Hardin’s work by looking at his chart history. The understated but penetrating work of the singer-songwriter from Eugene, Oregon figured only three times on the Billboard album chart, and never in its Top 100.

But Hardin wrote some of the most beautiful and enduring songs of his day. They included “How Can We Hang On To A Dream,” “Misty Roses,” and perhaps his two best-known pieces of work, the endlessly-covered “If I Were A Carpenter” and “Reason To Believe.” He died, of a drug overdose, on December 29, 1980, a few days after his 39th birthday. Much of his best work is anthologised on the Black Sheep Boy compilation released by Universal in 2002.

Born on December 23, 1941 in Eugene, Oregon, Hardin dropped out of school and joined the Marines before moving to New York and becoming immersed in the Greenwich Village folk scene. He recorded for Columbia, but that material wasn’t released until after he was with Verve Forecast, for whom he made his official album debut in 1966 with Tim Hardin 1.

From the opening “Don’t Make Promises” onwards, the LP unveiled a writer of unusual perception. It featured both “Reason To Believe” (later popularised by Rod Stewart) and “Misty Roses,” which was memorably interpreted by another fine British vocal stylist, Colin Blunstone, on his One Year album.

In 1967, Tim Hardin 2 featured his version of “If I Were A Carpenter,” which by then had already been a Top 10 US hit for Bobby Darin. Soon after the release of the Hardin album, “Carpenter” was brilliantly redefined in the soul genre by the Four Tops; other early readings included those by Johnny Rivers and Joan Baez, and the song has been covered scores of times since.

Commercially undervalued

For all that the song improved Hardin’s profile as a writer, his own recordings rarely made a commercial impression. He flickered onto the UK chart in 1967 with the gorgeous, haunting “How Can We Hang On To A Dream,” and in the US two years later with “Simple Song Of Freedom” — ironically, written by Darin, partly repaying his debt for the “Carpenter” cover.

By his own admission, Hardin was often uncomfortable in his social surroundings, given to extreme melancholy and unable to interact except through his work. “People understand me through my songs,” he told Disc and Music Echo in 1968. “It is my one way to communicate.”

Hardin performed at the Woodstock Festival and recorded a number of albums for Columbia, but by the 1970s he was battling a heroin addiction, and was only 31 when his last completed album Nine was released in 1973. It was not until after his death that appreciation for his work became evident among a new generation of artists, notably Paul Weller, whose post-Jam band the Style Council’s 1983 debut hit “Speak Like A Child” was named after a Hardin song.

Another longtime admirer was Roger Daltrey, who chose “Dream” for his commemorative CD of favorite music when he won the 2016 Music Industry Trusts Award for his services to music and charity. “I was a huge fan of Tim, the originator of ‘If I Were A Carpenter’ and ‘Reason To Believe,’” he said in the CD track notes.

Listen to the best of Tim Hardin on Apple Music and Spotify.

“But it’s all these other songs, ‘Misty Roses’…these writers, their lyrics are so on the edge,” mused Daltrey. “‘Hang On To A Dream’ has got something about it. I also like ‘Black Sheep Boy.’ People remember these artists’ songs, but they don’t remember them.”

Listen to the Singer-Songwriters: 100 Greatest Songs playlist.

Marc Time

December 31, 2019 at 6:17 am

Tim sang with kraut rockers Can when they were auditioning singers after Damo left the group.

Kevin Roberts

December 30, 2020 at 3:29 pm

It is true that Tim struggled. The first time we met in 1969, he had his face buried in his hands, hunched over in a chair and facing the corner. I turned away quickly and managed to hit a door and collapse to the floor, catching his attention. We had a nice talk, and I gave him a smile.

We met again the next day, when he ran for several long blocks after spotting me across a main road. He wanted to greet me and say hello and take my address. I thought he must be terribly lonely.

Several years later, Tim wrote me a letter scrawled in the margins of pages that he had torn from a magazine….the only paper available to this great poet of the heart.