‘Warm Leatherette’: How Grace Jones Crashed Into The 80s

With ‘Warm Leatherette,’ Grace Jones dragged the 70s into the 80s and defined the shape of the decade to come with a compelling take on New Wave.

As the 70s came to a close, Grace Jones was what could have been termed a “face,” if not quite a star. Anyone who was anyone on the disco scene instantly recognized her as an icon; anyone outside of that… perhaps less so. Early singles such as “I Need A Man” and a cover of “La Vie En Rose” saw Jones testing the bounds of her persona, if not wholly inhabiting it; meanwhile, the three albums she released during this period, Portfolio, Muse, and Fame, were classics of their type – but that was exactly the issue. They were classics of someone else’s type, rather than the product of Jones’ vision. Time to get out, find a different scene. In fact… time to create her own. Time for Warm Leatherette.

With Island co-founder Chris Blackwell, Jones decamped to Nassau, holing up in the now-iconic Compass Point Studios and working up an entirely new thing with the studio’s in-house band. Boasting Sly & Robbie as a crack rhythm section, along with the likes of keyboardist/guitarist Wally Badarou and percussionist Uziah “Sticky” Thompson, The Compass Point Allstars wrapped themselves around Jones’ vision: a curious mix of reggae, rock, New Wave, and club music. The results: one of the few albums of 1980, along with perhaps Prince’s Dirty Mind and David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), to truly kick-start the new decade.

More sparse than disco, more funky than New Wave, cold yet compelling, when it was released on May 9, 1980, Warm Leatherette’s stripped-down sound pointed to the future of early 80s club music, while its reggae jitters spearheaded a growing fascination with the music coming out of Jamaica. “Private Life,” the album’s second track and third single, is arguably the apogee of the album’s recording sessions. Along with Robbie Shakespeare’s streetwise bassline, Sly Dunbar’s paranoid percussion bursts try to hold anchor, but the keyboard squalls and guitar stabs act like an attack on the very foundations of the song.

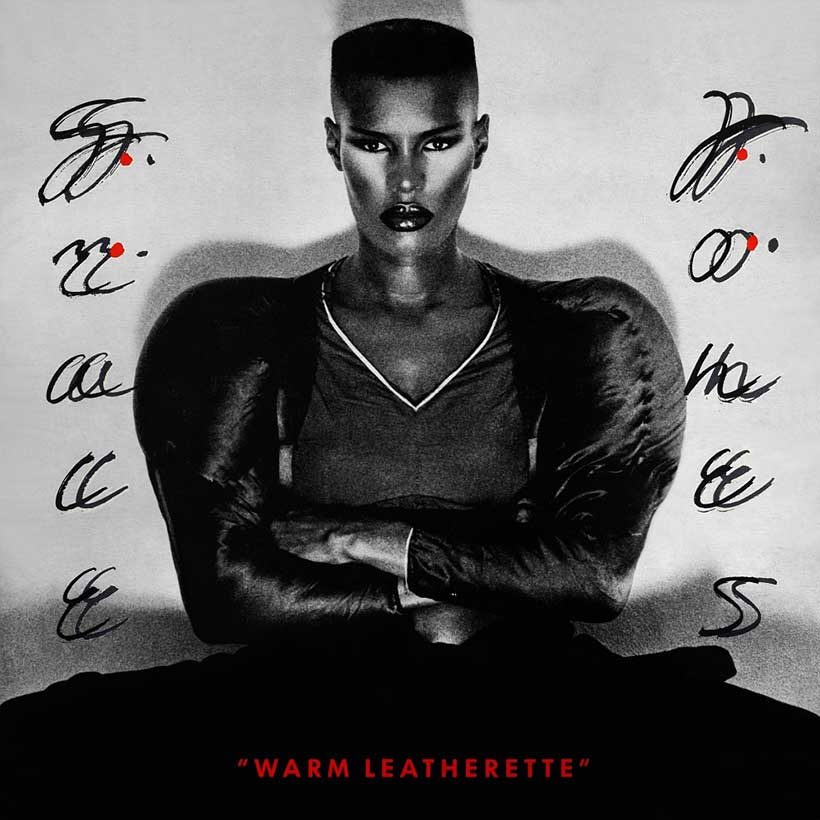

A complete re-imagining of Pretenders’ original, it’s danceable and unsettling all at once, and with Jones’ disdainful vocals (“Your marriage is a tragedy/It’s not my concern/… I feel pity when you lie/Contempt when you cry”), it’s also the musical equivalent of the pose she strikes on the album cover. As Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde has recalled on a number of occasions, when she heard it she felt this was exactly what the song should have sounded like.

Warm Leatherette would have been notable even if only for this song, but the seven cuts that surround it take the song’s template and mercilessly twist it into a variety of shapes. Co-penned by Jones herself, “A Rolling Stone”’s squelchy synths add an almost P-Funk touch to one of the album’s more carefully crafted songs – the only one that comes in at under four minutes (and which, perhaps unsurprisingly, was issued as the first single from the album, albeit only in the UK). It’s yet another signpost into the 80s, nudging up against a pop-R&B formula that would soon dominate the charts. (Jones’ all-conquering “Pull Up To The Bumper” was also recorded during the Warm Leatherette sessions; even more emblematic of the sound of 80s chart R&B, it was held back for a time when the world was ready.)

She wasn’t going quietly – nor was she going alone. Jones had found something new and she wanted to show everyone else the way. Covers of “Love Is The Drug” and “Breakdown” dragged the 70s into the new decade with her, the former turning Roxy Music’s sophisticated art-rock into a predatory cruise under neon lights, the latter reggaefying Tom Petty’s rock ballad, upending his resignation and turning it into an empowered casting away of romantic dead wood. (Like Hynde, Petty hailed Jones’ approach, and even penned an entirely new verse for her version of the song.)

Jones also cast her glare across British New Wave, picking up on an otherwise obscure B-side by The Normal (a one-man project by Daniel Miller, later founder of respected indie label Mute) for her title track. Arguably, however, in this instance she smoothed its rough edges – if not its confrontational heart. Miller’s original was a mechanical ode to the JG Ballard novel Crash (later turned into a controversial movie by David Cronenberg) but, in the hands of Jones and The Compass Point Allstars, the song found a new groove, making the fetishism at its heart dangerously palatable.

Warm Leatherette made a star out of Jones and set the template for whole swathes of bands in the decade to come. But while Jones’ album was an amalgamation of styles, others would have to remain content teasing out its separate elements: the glacial synth-pop that found a home in the clubs; reggae-rock crossover that found traction on the charts. Just a couple of months after the album’s release, The Police would start recording their heavily reggae-indebted Zenyatta Mondatta, while Tom Tom Club, emerging from New Wave icons Talking Heads, would follow Jones from New York to Compass Point for their self-titled debut. (Lizzy Mercier Descloux, a French transplant who’d befriended Patti Smith and become a cult figure with the CBGB crowd, would also head to the studio at Chris Blackwell’s behest.)

But Jones was the original: the innovator, the hunter – not captured by the game, but setting the rules even as she broke them.