Interplanetary Travels On Otherworldly Sounds: How The Stratosphere Influenced What We Hear

A look at the many musicians who have played out their lunar obsession in song.

Since time immemorial, we earthlings have been fascinated by space and the possibility that life might exist on other planets. Our vision has sometimes been apocalyptic (HG Wells’ 1898 novel The War Of The Worlds), sometimes benign (Stephen Spielberg’s 1982 blockbuster ET: The Extra-Terrestrial), but always highly imaginative – and it’s no wonder that, as advancements in technology made it possible for musicians to wring ever stranger sounds from their instruments, our interplanetary obsessions have been played out in song.

In 1962, with the space race in full flow, Joe Meek tapped into the public’s fascination when he penned “Telstar,” an instrumental hit for British group The Tornados. Recorded in the London flat that Meek used as a studio, the track, inspired by the July 10, 1962 launch of the communications satellite of the same name, quickly went interstellar and topped the US Billboard Hot 100. Propelled by its distinctive clavioline sound, “Telstar” gave listeners their first taste of space travel: this is what it must have sounded like, coming of home speakers.

By the end of the decade, the Moon landing had sent the world into a frenzy. Outsider rockabilly musician Legendary Stardust Cowboy issued “I Took A Trip On A Gemini Spaceship” in 1969, a song whose woozy mix of drum kit-down-the-stairs percussion and keyboard glissandos created a truly spaced-out atmosphere. It certainly caught the ear of a young David Bowie, who that year went stratospheric when he released “Space Oddity.” Putting himself in the mindset of Major Tom, a lonesome traveler “sitting in a tin can far above the world,” Bowie enlisted Rick Wakeman to give the song a Mellotron-aided weightlessness, while his own Stylophone contributions were beamed in like Morse code from other stars.

Bowie’s obsession with space was a long-term thing – from “Life On Mars?” to The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust and even a 2002 cover of the Stardust Cowboy’s “Gemini Spaceship.” Certainly, he helped elevate science-fiction from a niche concern to acceptably mainstream subject matter. Elton John looked to “Space Oddity” for inspiration when he released “Rocket Man” in 1972, while former Velvet Underground frontman Lou Reed enlisted Bowie to perform production duties on Transformer, an album that included the stargazing “Satellite Of Love.”

While Bowie had created a character for himself to embody, avant-garde jazz psychonaut Sun Ra fully claimed to have descended to Earth from Saturn. Leading his Arkestra, Ra’s self-professed mission was to spread peace and love throughout the universe with his Afro-futurist jazz. Ranging from swing to fusion freak outs, Ra’s overwhelmingly large discography is a universe unto itself. Miles Davis, meanwhile, was a far more grounded personality, but the fusion experiments that he started with 1970’s Bitches Brew led him into galaxy’s furthest extremes. By the time he released live recording Agharta, in 1975, his band were seemingly tearing rifts in the time-space continuum on a nightly basis.

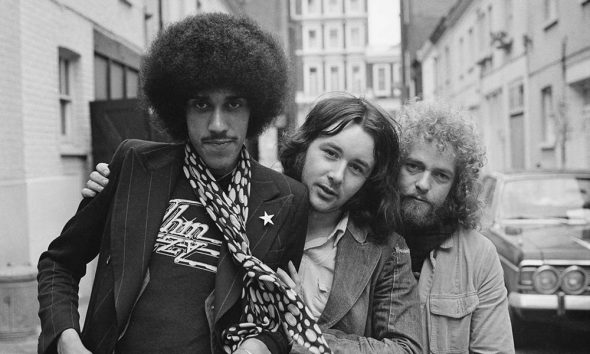

Emerging from the late 60s psych underground, a breed of bands given the umbrella term “space-rock” took from free jazz and fusion to push the boundaries of what a rock group was capable of. Pink Floyd went into “Interstellar Overdrive” as early as 1967, while Hawkwind, perhaps the archetypal space-rock band, went In Search Of Space in 1972, taking soon-to-be Motörhead frontman Lemmy with them on “Silver Machine.” Over in Paris, meanwhile, Daevid Allen had formed Gong, a progressive outfit whose early jazz-influenced excursions included cornetist Don Cherry, and who eventually created their own mythology, notably on the “Radio Gnome Trilogy,” which launched in 1973 with Flying Teapot, and followed the interplanetary travels of Zero The Hero.

Parisian avant-rockers Magma took mythologizing to its fullest with over 20 live and studio albums (and counting) that tell the continuing story of life on the planet Kobïa, all sung in Magma mastermind Christian Vander’s invented language, Kobïan (a kind of Klingon for the space-rock fraternity).

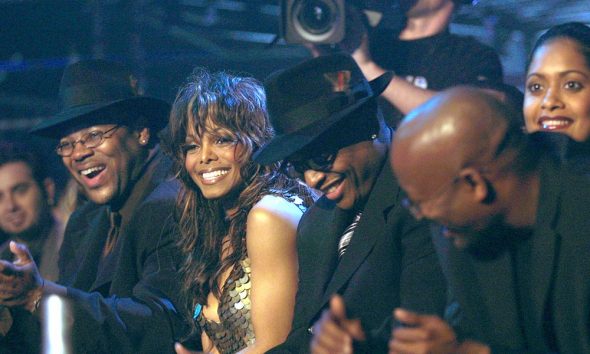

Not that intergalactic warfare was the preserve of cerebral rockers playing to crowds of head-nodding devotees. As far as George Clinton was concerned, there was a booty-shaking battle to be won, and his Parliafunkadelicment Thang collective urged listeners to “free your mind and your ass will follow.” Under the Parliament banner, Clinton envisioned a clash between the likes of the perennially unfunky Sir Nose D’Voidoffunk and the Bop Gun-wielding Star Child, aided by Dr. Funkenstein. A series of albums, beginning with Mothership Connection, brought the story to life, while, during live shows, the P-Funk crew landed a full-sized mothership on stage for Clinton to emerge from.

Kraftwerk, too, used props to bring their world to life in the 70s, going so far as to send robot doppelgangers on stage in their place. It all added to their finely tuned mythology – “We are the robots” they wryly declared on their groundbreaking 1978 album The Man-Machine, and fans eagerly agreed.

That album included “Spacelab,” a largely instrumental song that picked up from where Joe Meek left off with “Telstar”: there was no need to sing about space when the technology at hand enabled you to conjure it in the studio. Kraftwerk’s pioneering use of synths and keyboards was echoed by fellow German explorers Tangerine Dream, who took their listeners on increasingly out-there journeys with albums the likes of Phaedra and Rubycon, each one seemingly touching down in a new musical gallery. Vangelis, too, embraced the new possibilities, the likes of Blade Runner’s “Love Theme” adding to a growing stream of music which Brian Eno termed “ambient.”

Unsurprisingly, Eno would create many unimpeachable masterpieces in the ambient genre, not least Apollo: Atmospheres And Soundtracks, a 1983 collaboration with his brother Roger and Daniel Lanois. A little under a decade later, that album would inspire The Orb to record Adventures Beyond The Ultraworld, spearheading what the group called “ambient house” music.

Ultraworld was, essentially, a space excursion that took place entirely in the mind. As such, it’s a reminder that the universe might, in theory, be limitless, but so is the human brain’s capacity for invention. Planet Earth’s cultural and creative diversity was celebrated in 1977, when NASA launched the Voyager spacecraft, which carried on board the Voyager Golden Record. Containing a variety of natural sounds found on Earth, along with audio greetings in 59 languages, the disc also included 90 minutes’ worth of music from countries as far-flung as Germany, Mexico, the UK, Indonesia, and Peru, showcasing a dazzling array of styles, from vocal chants to indigenous folk and jazz, courtesy of Louis Armstrong’s “Melancholy Blues.” Whether it will ever find its way to alien ears remains to be seen.