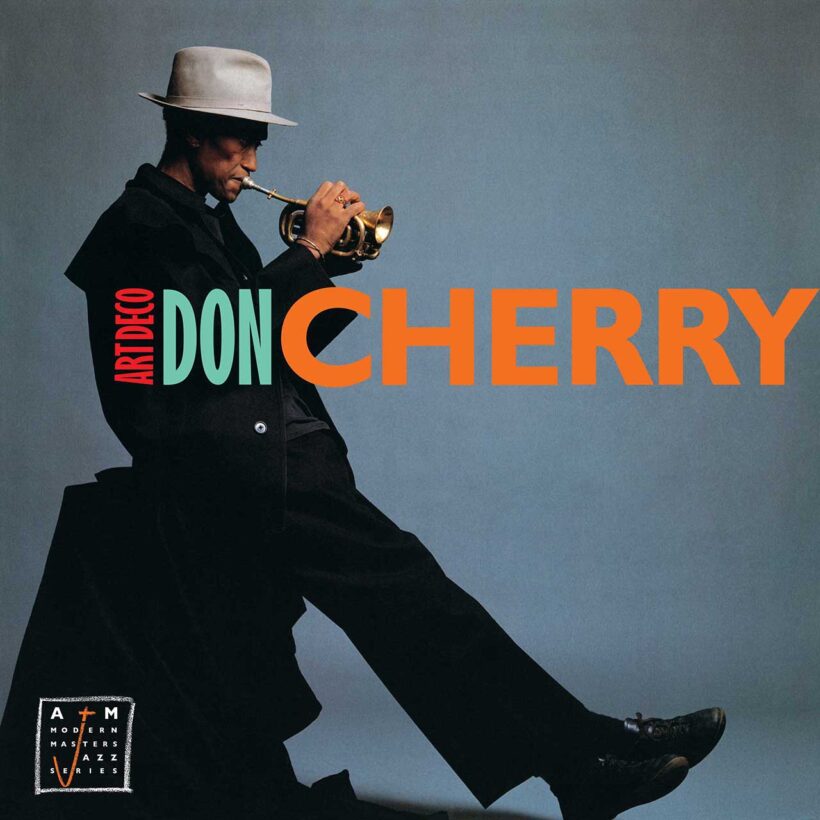

‘Art Deco’: Don Cherry’s Affectionate Look-Back

A delightfully semi-straight album in a career that continually pushed far beyond the sphere of expectation.

Don Cherry’s status as a jazz iconoclast was cemented as a fixture on pocket trumpet opposite Ornette Coleman’s plastic alto in the latter’s revolutionary late ’50s/early ’60s groups. A disciple of Coleman’s Harmolodics theory – which dispensed with the guard rails of chord changes for the freedom of intuitive soloing – Cherry would eventually dispense with traditional U.S. domestic life altogether as well. By the late ’60s he’d settled in Sweden (with his partner, artist Moki and her daughter Neneh, and Don and Moki’s young son Eagle-Eye), immersed himself in non-Western scales, instrumentation and voicings, and workshopped and developed his own collage approach to extended communal improvisation. “Organic music” would be an apt self-styled handle for his pan-ethnomusicological adventures. “I wasn’t playing for jazz audiences then, you realize,” he told Musician magazine in 1983. “I was playing for goat herders who would take out their flutes and join me and for anyone else who wanted to listen or to sing and play along. It was the whole idea of organic music — music as a natural part of your day.”

All of which makes 1989’s Art Deco a delightfully semi-straight zig in a career that continually zagged well beyond the sphere of expectation. The first in A&M Records’ Modern Masters Series of releases, the album returns Cherry to his roots as a young trumpeter in Watts, Los Angeles still enthralled by bop but newly inculcated in Coleman’s groundbreaking concepts. It also reunites him with his original Coleman quartet compatriots Charlie Haden on bass and Billy Higgins on drums, and a less renowned associate from those heady early days, James Clay. A classically robust “Texas tenor,” Clay won admirers amongst both L.A.’s young avant-garde-ists and conservative elders through the intuitive fluidity and emotive weight of his playing. A mainstream soloist who nonetheless understood Coleman’s compositions, he was forced to return to Dallas before he could record with the group that would go on to famously disrupt the jazz world.

So while Cherry is ostensibly the leader here, his communal ethos and the collective’s desire to give Clay his long overdue flowers combine for a program of largely bop-centric material that retains a genuine, familiar warmth. The group bounces beguilingly through tracks like the lovely title cut, a Cherry original, and a take of Monk’s “Bemsha Swing”; Cherry channels the timbric spirit of Miles via lean muted lines, Clay serves as his vigorous and enthralling counterpart. Two Coleman pieces from his pre-Shape of Jazz to Come repertoire, “When Will the Blues Leave” and “The Blessing,” gently challenge Clay, and he acclimates himself well, his horn darting fluently around and about the tonal centers of their melodic themes. Solo sketches allow Cherry, Higgins and Haden room to riff and ruminate in vignette (Haden’s “Folk Medley” being particularly radiant) – while Clay is fully in his bag on two beautifully performed standards that Cherry entirely sits out, “Body and Soul” and “I’ve Grown Accustomed To Your Face.”

Art Deco’s finale, and its most explicitly “outside” track, finds the quartet tackling another Coleman composition, “Compute,” as though answering a “What if?” Specifically, what if Clay had not departed L.A. all those years ago and sustained a more than tangential connection to his avant-garde colleagues? The resulting sparks suggest an intriguing juxtaposition – the traditional Texas tenor navigating a Southland free jazz twister. It also forecasts Cherry’s inevitable restlessness. His next LP, 1990’s Multikulti, would find him once again experimenting in fascinating ways, making Art Deco’s affectionate look back but a brief pause before resuming the unpredictable path forward.