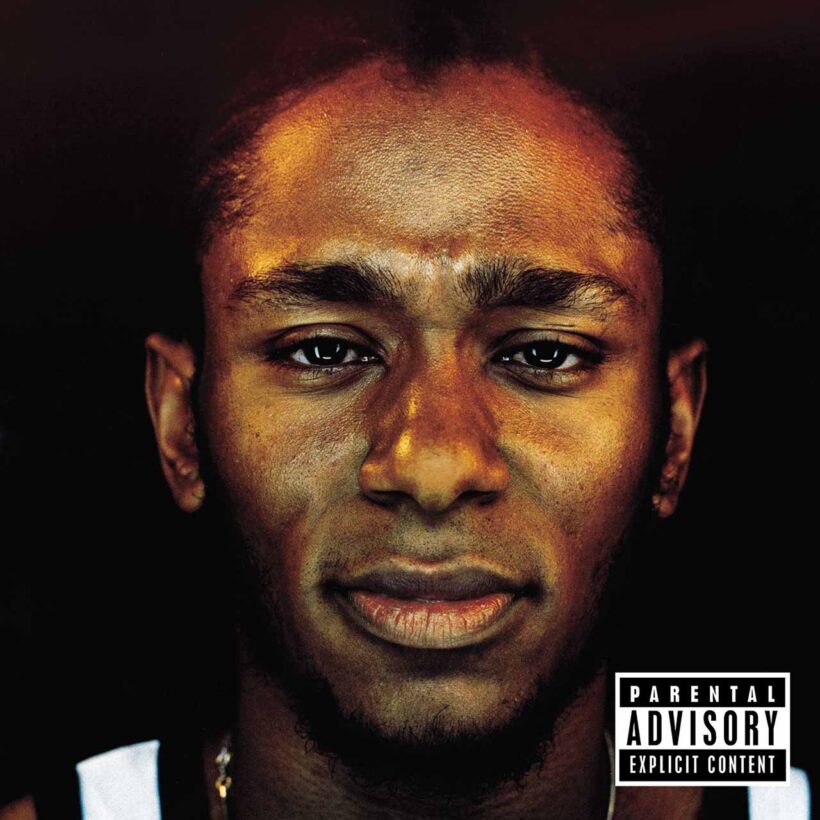

‘Black On Both Sides’: Mos Def’s Solo Masterpiece

Yasiin Bey never embraced the conscious rap label. But no one embodied it quite like him.

Yasiin Bey never embraced the conscious rap label. But no one embodied it quite like him. He came on the scene with Talib Kweli as Black Star, a duo that dropped their eponymous debut album in 1998. Merging Native Tongues aesthetics with themes of Afrocentrism, the project established Bey and Kweli as streetwise poets with a message – twin messiahs of so-called rap consciousness. Then known as Mos Def, Bey expanded his scope further with Black on Both Sides, a debut solo effort that’s as mesmerizing as it is eclectic. Released in 1999, the album represented all the most positive stereotypes of conscious rap, while cementing Bey’s status as a virtuoso MC.

Checking in at an hour-and-12 minutes, Black on Both Sides is as sprawling as the African diaspora itself, shifting between apex boom bap (“Hip Hop”), wandering jazz (“UMI Says”), and screeching punk (“Rock n Roll”). He threads it all with floral writing, lucid introspection, and an unsparing eye for humanity. He can be playful or deadly serious, real-time specific or artfully abstract. For “Ms. Fat Booty,” he coasts over an Aretha Franklin sample to unspool a tale of a romance that almost was. He recalls a woman placing her arms atop his shoulder blades while grafting the beat with the wit of a self-aware playboy: “I understand, I’m feeling you/Besides, ‘Can I have a dance’ ain’t really that original.” Elsewhere, for the DJ Premier-produced “Mathematics,” he explains why it’s “dangerous to dream” in a world dictated by hard numbers instead of prayers.

Listen to Mos Def’s Black on Both Sides now.

He renders this all through spurts of metaphysical poetry. You could argue that Bey is verbose, but this isn’t someone trying to sound smart; he’s trying to distill infinite, macrocosmic truths, and he just so happens to be creative enough to find appropriately grand vessels for them. Layered in metaphors, his stanzas can play out like a vision of everything that is, was, and will ever be. “Hip Hop is prosecution evidence/An out of court settlement, ad space for liquor/Sick without benefits/Luxury tenements/Choking the skyline, it’s low life getting tree-top high/It is a backwater remedy/Bitter and tender memory, a class E felony,” he raps on “Hip Hop.”

Bey can be as technical as the best rap technicians. But tracks like “UMI Says” are exercises in freeform meditation, with his wailing murmurs and meandering bassline evoking warmth and spirituality. That experimentation continues on tracks like “Brooklyn,” where he opens with a Red Hot Chilli Peppers interpolation before sliding over instrumentals from three legendary New York acts from various enclaves of hip-hop. It’s at once a dexterous rhyme exhibition and a rebellion against classification. Bey didn’t color outside of the lines; he refused to acknowledge that they even existed in the first place, scribbling his thoughts and sensations in the most unwieldy, but majestic patterns he could conjure.

Situated between the post-Tupac and Biggie rapperverse and the shiny suit era, Black on Both Sides stood as a supposed antidote to rap commercialism. On a practical level, it was simply an instant classic – an album that appealed to both casual rap listeners and seasoned fanatics. The first Black Star album remains unimpeachable. Yet, decades after its release, Black on Both Sides stands as the moment Mighty Mos Def was at his mightiest.