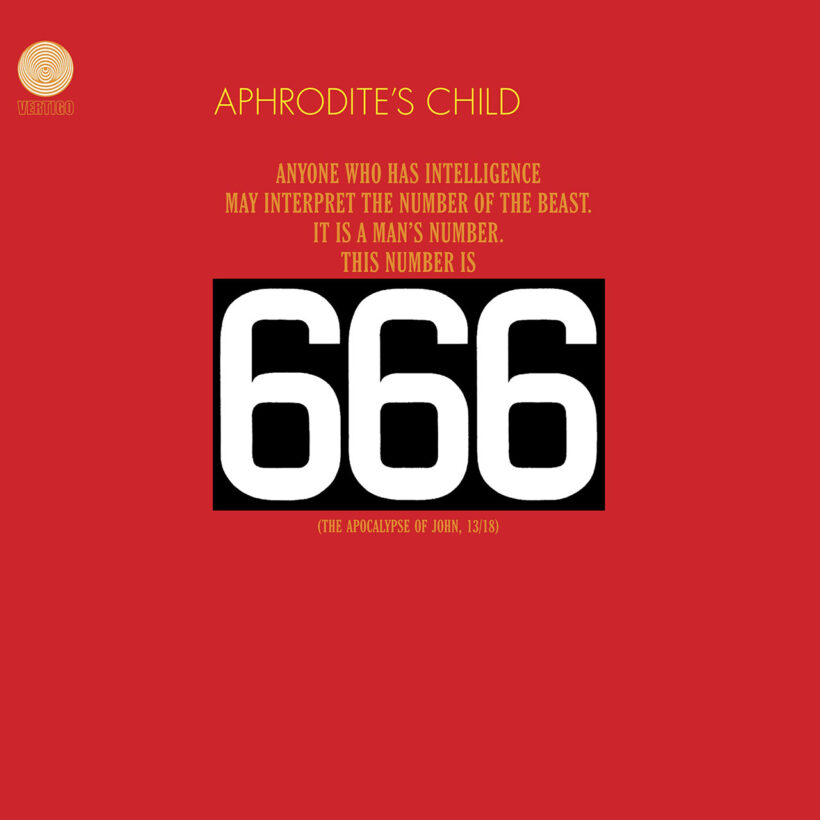

‘666’: The Mind-Bending Aphrodite’s Child Masterpiece

Featuring Vangelis and Demis Roussos, the album still inspires wonder decades after its release.

It’s a wonder that Aphrodite’s Child’s 666 ever got made at all. The Greek group had made two albums in the 1960s before their country was thrown into chaos via a right-wing military coup. Two of the three musicians – keyboardist Vangelis and singer/bassist Demis Roussos – fled to Paris, while guitarist Anagyros (Silver) Koulouris stayed behind, pressed into military service. By the time Koulouris rejoined the group, Roussos was starting up a solo career that would eventually lead to huge pop success. And Vangelis had become a studio hermit, allowing a replacement to take his place on tours. The next album that Vangelis had planned? A collaboration with film director / lyricist Costas Ferris based loosely on the Book of Revelation. The idea didn’t sit well with either the band or its label, Mercury. When the imprint heard 666, they demanded that certain tracks be pulled.

As the album continued to sit in limbo, the band decided to hold a party in Paris to celebrate the first “birthday” of its non-release. Among the invitees was none other than Salvador Dali. According to Costas, “Just before… blowing the candle of the so-called negative anniversary, Dali arrived, surrounded by his bodyguards and friends. He became immediately the king of the event. So, he asked to sit on his ‘throne,’ and hear the whole music! Almost 80 minutes! In silence!” Dali pronounced it “a music of stone” and said it reminded him of the church of Sagrada Famiglia in Barcelona. Mercury agreed to release it. (But only on its freakier Vertigo subsidiary.)

Order the Aphrodite’s Child album 666 on vinyl now.

Listening to the album today, you can’t fault the label for getting cold feet. The record begins with the distant but clear chant of “F–k the system,” a word allowed on very few records in 1971. Later on, there’s a track called “Infinity Symbol,” which contains perhaps the most vivid recorded orgasm in popular music. (Far more realistic than Donna Summer or Jane Birkin, even.) The actress Irene Pappas does the honors, getting the full five-minute track to herself aside from some tribal drums. Her chanting of a Biblical paraphrase – “I am, to come, I was” – is punctuated by shrieks, groans, heavy breaths and more. It’s a remarkable performance and one of the few moments of actual erotica in the prog canon.

In 1971, there was very little to compare 666 to. Sure, it’s a double concept album with a Biblical theme and a climactic 19-minute track – but that still doesn’t place it anywhere near the symphonic prog territory of Yes and ELP, or even the jazzier turf of early King Crimson. Aphrodite’s Child were simply a lot further out: A mix of Hawkwind-esque psychedelia, Zappa-style cutting and pasting, and a lot of spoken word. Top it with a keyboardist whose style was just as informed by the classics as it was European cinematic music. Then throw some straight-ahead heavy rock into the mix whenever you least expect it, and you’ve got an idea of what 666 was all about.

All things considered, it’s a fairly loose concept album – Vangelis wrote that he intended it to be “looser than Tommy, but more rigid and strict than Sgt. Pepper’s” – and much of the story is told through instrumental music alone. There are in fact only five conventional vocals on the whole double album, and those stand out for being so incongruous. The first proper song, “Babylon” has a heavy acoustic guitar, an upfront bass and a grabbing chorus hook; with a different lyric it could be the Move or the Small Faces. “The Four Horsemen” flashes back to the band’s heavy-psych days; Koulouris’ wah-wah extravaganza shows his clear intent to make up for his time away from the band.

If you only know Vangelis’ celebrated soundtrack work, his playing here will be a revelation. He didn’t yet have his trademark banks of synthesizers, so he got especially resourceful with the keyboards he had. Conventional sounds (like the Hammond B3 beloved by Wakeman and Emerson) weren’t for him, and you can’t always tell exactly what he’s playing. The album’s first instrumental, “The Lamb,” is a sprightly piece with a dialogue between two keyboards: One could be a sped-up piano or just a normal one played especially fast; the other is an organ distorted to sound like bagpipes. On “Altamont” he takes to the vibes; though it refers to a tragic event, the track has an almost celebratory rock feel.

Covering most of side four, “All the Seats Were Occupied” takes the full journey from order to chaos. The opening section is built around a stately, melodic theme that’s the first real glimpse of Vangelis’ soundtrack success. But the piece becomes more unsettling: There’s another big guitar unleashing by Koulouris; a stretch of monastic chanting, and reprises of many previous tracks, and the world finally ends with…a drum solo. Yet there is hope in the distance: The album concludes with “Break,” an anthemic ballad that promises new beginnings while bringing the band full circle, harking back to “Rain & Tears” territory.

After that, there was simply no place for Aphrodite’s Child to go. Demis Roussos ultimately became a European pop star; his mid-70s hit “Happy to Be on An Island in the Sun” sounded for all the world like an Aegean Sea version of Jimmy Buffett. Vangelis came tantalizingly close to joining Yes in 1974 (they went with Patrick Moraz instead); getting worldwide fame for Chariots of Fire and his Jon Anderson collaborations. So 666 will forever be an artistic one-off, and an eternal mind-blower.