The Grit And Grace Of The Band’s Unsung Years

The Band’s first three albums remain one of the most magical hat tricks in music history. But don’t stop listening there.

The Band’s first three albums remain one of the most magical hat tricks in music history. But don’t stop listening there.

If 1968’s Music from Big Pink, the self-titled 1969 follow-up, and 1970’s Stage Fright were comprised of physical rock instead of the musical kind, they’d be gazing imperiously out of Mt. Rushmore. With tunes like “The Weight,” “Chest Fever,” “Up on Cripple Creek,” and “The Shape I’m In,” to name only a few, The Band put Americana on the rock ‘n’ roll map and created a template that roots rockers are still following today. But after that, casual observers usually skip straight to The Band’s legendary live farewell album, 1978’s The Last Waltz, missing out on many songs that were crucial to the catalog.

Explore the best of The Band’s discography on vinyl and more.

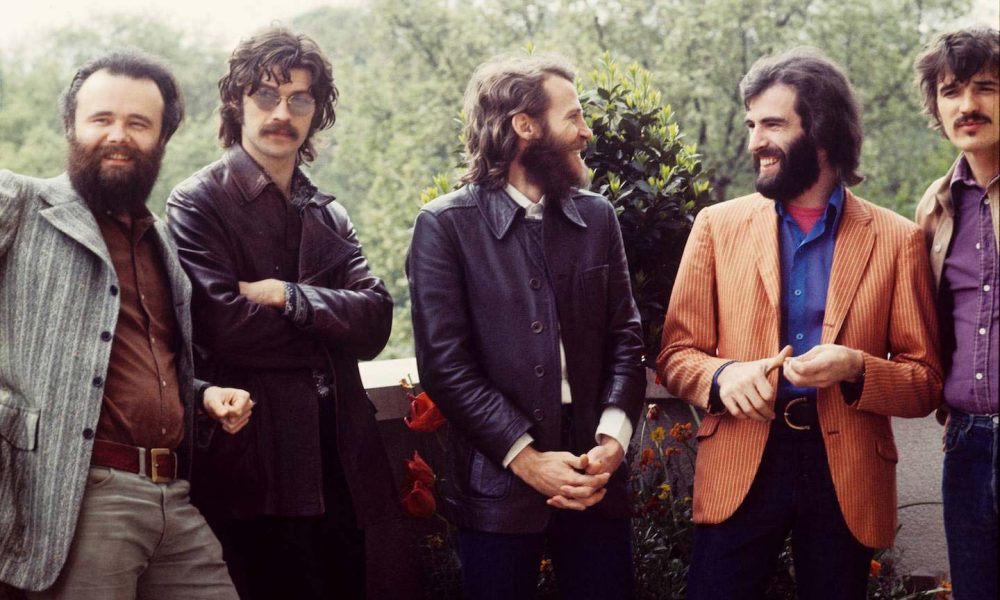

Between Stage Fright and The Last Waltz, The Band turned out four studio albums that remain largely unsung. But while the members’ increasingly fractious working dynamic complicated the records’ construction, each one contains cuts ranking right alongside the best the Canadian-American quintet had to offer.

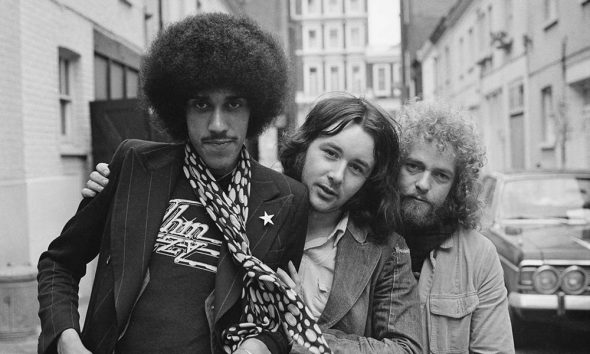

By the time of Stage Fright’s release, things were already unwinding pretty quickly for The Band. Substance abuse was taking its toll, and success only worsened the problem. Levon Helm, Robbie Robertson, Richard Manuel, Rick Danko, and Garth Hudson were five spiritual siblings who more or less came of age together, working the club circuit from the late 50s through the mid-60s with singer Ronnie Hawkins and then, on their own. But they were growing distant, and collaboration became a task instead of a joy. Manuel, in particular, was disappearing into his addictions and no longer contributing material.

But The Band was too far in to turn back. They convened at their manager Albert Grossman’s newly built Bearsville Sound Studio in Woodstock to cut 1971’s Cahoots. In the notes for the album’s reissue, Robertson remembered, “We never had a studio before to experiment and play with… But we weren’t making an album. It was really just messing around and trying to come up with some stuff. It turned out that in there, somewhere, there was a magic.”

The studio setup and the internal fraying of The Band led to a newly ad hoc record-making process, where only a couple of songs were written ahead of time. “Guys were showing up, and I was just playing the song for them at the last minute,” recalled Robertson, “and then we would start to figure out what to do on it.”

Against the odds, they assembled a worthy follow-up to Stage Fright. Quirkier and more complex than its predecessors, Cahoots contains odd timings and unusual structures, but it also overflows with pathos and passion. An aching undercurrent of loss occurs throughout. One of the album’s most arresting tracks, “Last of the Blacksmiths,” recounts leaving Canada to find fame in the U.S. and feeling queasy about the consequences. When Manuel sings, “Frozen fingers at the keyboard, could this be the big reward,” it rings with an eerie resonance.

The Band’s Woodstock-dwelling pal Van Morrison turned up to co-write and sing on the rock ‘n’ roll stroll “4% Pantomime.” Tellingly, the first verse depicts a dissolute response to music biz machinations, but there’s an indomitable swing to the Manuel/Morrison-fronted tune. “Well, that was Richard and Van,” Levon Helm told MOJO’s Andy Gill in 2000. “You couldn’t kill that kind of friendship and creativity. You get them together, you bet your ass it’s gonna get good!”

Cahoots’ most hopeful song, and probably the funkiest in The Band’s catalog, “Life Is a Carnival,” sports a bemused attitude toward the world’s vagaries. It’s a lot easier to keep smiling when you’ve got a jubilant Allen Toussaint horn chart moving you along. The New Orleans R&B king’s contribution came off so well The Band brought him back to arrange the horns for the December ‘71 shows captured on the classic 1972 concert album Rock of Ages.

Despite Cahoots’ considerable charms, it started a trend of diminishing commercial results. The group’s internal troubles only deepened. Instead of a new batch of Band compositions, 1973’s Moondog Matinee offered covers of vintage rock ‘n’ roll and R&B tunes.

People weren’t quite prepared yet for the concept of countercultural heroes saluting the Eisenhower era. Moondog Matinee arrived the same month as David Bowie’s similarly styled Pin Ups, and a couple of years ahead of John Lennon’s 50s salute, Rock ‘n’ Roll. Zoo World’s Arthur Levy even declared the record “destined to be the most misunderstood, neglected album of 1973.”

“It would have been much easier to make another Band album,” Robertson later told Melody Maker’s Harvey Kubernik. “Here you have to compete with yourself, the old songs, and these artists… Unfortunately, people, rather than taking it for what it was, always compare it to something else you’ve done. I think it’s ridiculous to compare ‘Moondog Matinee’ to ‘Big Pink’ or ‘Rock of Ages’.”

Manuel had always been able to tap into his inner well of sorrow and turn out transcendent performances, and his vocal brought an almost tragic gravitas to The Band’s take on the Platters’ smash “The Great Pretender.” Taking the lead on hard-charging R&B pumpers like Fats Domino’s “I’m Ready” and Clarence “Frogman” Henry’s “Ain’t Got No Home,” Levon Helm unleashes all the lusty, loose-limbed abandon at the heart of The Band’s early influences.

In 2002, Helm told GRITZ’s Mitch Lopate, “Nobody gave us credit for it – the critics certainly didn’t, and the record company, they didn’t know what was going on, anyway. That was all we could do at the time. We couldn’t get along.”

For 1976’s Northern Lights-Southern Cross, Robertson crafted the first bunch of new Band tunes in four years and the last of the group’s initial run. By this time, The Band had relocated to the opposite coast, but emotionally, they were further apart than ever.

Somehow, they made it work. It surely didn’t hurt that the funky “Ophelia,” the poignant tale of 18th century Acadian deportation “Acadian Driftwood,” and the heart-stabbing ballad “It Makes No Difference” rank among Robertson’s most affecting compositions. But the performances help put the songs over the line.

Garth Hudson’s organic, utterly idiosyncratic synthesizer work on the album was celebrated by Levon in his book, This Wheel’s on Fire. “[The Band’s studio] Shangri-La had 24 tracks,” Helm said, “and Garth used that leeway to craft as many as half a dozen keyboard tracks on a single song.” In his memoir, Testimony, Robertson recalled Hudson’s playing on “Ophelia,” saying, “The combination of horns and keyboards Garth overdubbed on this song was one of the very best things I’d ever heard him do.”

And Robertson’s lead guitar — one of The Band’s secret weapons – was seldom as taut and visceral as it is on “Forbidden Fruit” and “It Makes No Difference.” But there was still no stopping The Band from edging toward the end of their road. “‘Northern Lights-Southern Cross’ was the best record we’d made since ‘The Band’ in 1969,” wrote Helm, “but Capitol couldn’t break the first single, ‘Ophelia,’ on the radio.”

The Band called it quits later that year, marking the occasion with the triumphant Thanksgiving 1976 concert captured on the historic 1978 documentary and soundtrack album, The Last Waltz. Prior to the film and record’s release, The Band released 1977’s Islands, a collection of outtakes from the last several years.

What could have been a perfunctory exercise in a lesser band’s hands boasted cuts other artists would have killed for. The simultaneously trippy and earthy “The Saga of Pepot Rouge” and the New Orleans-fried Depression-era snapshot “Knockin’ Lost John” would brighten up anybody’s album. And when Manuel locks his lungs onto “Georgia on My Mind”— he establishes himself as perhaps the only singer who could go toe-to-toe with Ray Charles on the tune.

In 1978, looking back on life on the road with The Band, Robertson told NME’s Mick Farren, “It’s very hard, emotionally. You drink a lot, it makes a lot of people take drugs, anything to take the edge off it. It’s basically an impossible, unnatural way of life.”

But The Band’s 1972-’77 studio sets prove one thing definitively, Levon, Robbie, Richard, Garth, and Rick’s personal struggles may have taken a lot out of them, but even when they were down, they delivered.