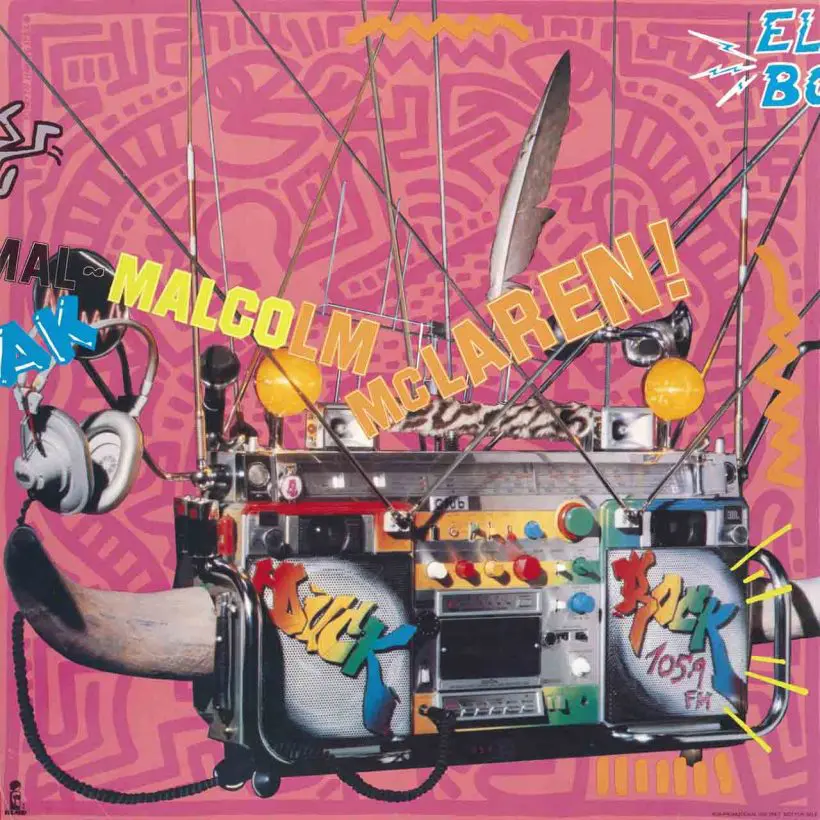

‘Duck Rock’: Malcolm McLaren’s Fascinating 1983 Album

The album blended together sounds from around the world. It’s a strange listen, decades later.

Cultural appropriation is a difficult topic to talk about today. During the 1980s, it was barely mentioned. So much music from that decade, however, serves as fodder for debate. There’s Paul Simon’s Graceland, of course, which introduced a variety of South African styles to Western listeners. Encouraged by that album’s success, compilations of folk and traditional music from across the globe became de rigeur at record stores. And, soon, “worldbeat” became a popular genre in its own right, renowned for its fusions of “world music” with Western pop and rock.

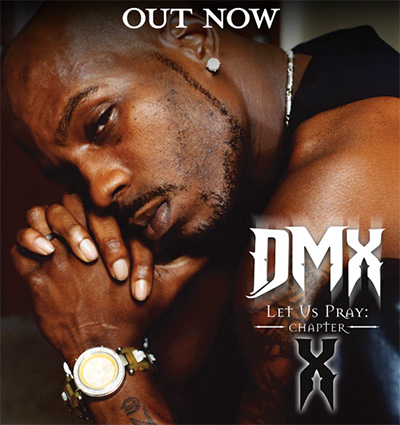

Before these efforts were commonplace in the music industry, however, one controversial British impresario made one of the most nakedly appropriative records in music history. Malcolm McLaren made his name as a music promoter and band manager. Notorious for his unconventional marketing tactics, McLaren’s work with The New York Dolls, Bow Wow Wow, and most notably, The Sex Pistols, became the stuff of legend.

Listen to Malcolm McLaren’s Duck Rock now.

In 1983, McLaren tried his hand at music, releasing his debut album, Duck Rock. Given his background in punk and New Wave, you’d be forgiven for thinking McLaren’s debut would swim in similar waters. Instead, in a characteristically eccentric move, McLaren attempted to unite a variety of styles with which he had almost no experience. Tied together via a hip-hop approach, McLaren put out a record that combined everything from South African mbaqanga to merengue to square dance-style country.

Duck Rock’s strengths are less a testament to McLaren – who couldn’t compose or perform music – as they are to the myriad musicians and composers whose work he used. Indeed, beyond his work scouting talent, McLaren is, for all intents and purposes, a DJ on Duck Rock, his contributions limited to curation and sporadic ad-libs.

According to producer Trevor Horn, “[Malcolm] had no sense of pitch or rhythm.” In an interview with Red Bull Music Academy, Trevor remembers hitting McLaren in the chest in time to the record. “So I’m standing there doing this, but after about four takes I start to get tired. He [said]: ‘You’ve gotta keep hitting me. Come on, what’s your problem?’” Horn’s response? “I’m exhausted, Malcolm.” At times, it’s difficult to avoid the fact that McLaren sounds like a musical Austin Powers, yelling goofy commands from behind the decks. Duck Rock’s featured hip-hop radio hosts, The World’s Famous Supreme Team, jokingly called McLaren a “vibe-killer.”

The album’s source material – often uncredited – deserves celebration. At its core, Duck Rock is a compilation of pre-existing music, produced and mixed for a Western pop audience. “Double Dutch” – one of the album’s biggest hits – used a track called “Puleng” by South African mbaqanga group, The Boyoyo Boys. “Punk It Up” is a reproduction of Mahotella Queens’ “Kgarebe Tsaga Mothusi.” “Jive My Baby” is another Mahotella Queens’ composition, “Thina Siyakhanyisa.” “Song for Chango” – which was bafflingly credited to only Horn and McClaren – is a rendition of an age-old Cuban tune, “Elube Changó.” The joyous “Soweto” is taken from a track called “He Mdjadji” by MD Shirinda & the Gaza Sisters. Elsewhere, there are performances from unnamed Cuban musicians, a range of Zulu artists, an uncredited wedding band called Lewis Khalif and his Happy Dominicans, and an assortment of session musicians from Tennessee.

Despite its questionable reputation, Duck Rock remains a fascinating document of an era in which questions about sampling and appropriation were only starting to be asked. And, for Western audiences in 1983, it no doubt introduced sounds unheard of in popular music. It’s almost impossible to imagine a record like it ever being made again.