‘What A Place To Be’: John Illsley Chronicles His Life And Times In Dire Straits

Illsley’s new book is a celebration of the band’s achievements and of his enduring friendship with Mark Knopfler.

When John Illsley was writing and demo’ing for his imminent eighth solo album, the last thing on his mind was to chronicle his remarkable past as a co-founder of one of the biggest bands in rock history. But lockdown did some strange things, and not all of them were bad. The album is ready to go in 2022, accompanied by live shows, and with his autobiography My Life In Dire Straits newly published by Bantam Press.

Illsley, co-founding bassist with the 120 million-selling group, set out on their unforgettable adventures in 1977 with his close friend Mark Knopfler, Mark’s brother David (as initial rhythm guitarist) and Pick Withers on drums. Illsley not only had approval for the memoir from Mark but elicited a foreword from him that describes the “hell of a ride” they went on together. Illsley, he writes, “was a great companion for the trip the band took, and he continues to be a great mate today.”

That continuing bond between the pair, and a deep affection for what they went through in 15-some years of Dire Straits, glows from the pages of Illsley’s narrative. From loading in their own equipment down beer chutes of London clubs to playing for seven million people on their final 1992 tour, he paints the expanding insanity of their global conquest, in a tale thick with unlikely characters, wild highs and inescapable downs. More than that, he describes the relationship that came through it all, which he values above any platinum disc.

“The main thing for me is celebrating something, celebrating a friendship that I’ve had for 40-odd years, and a musical partnership,” says Illsley. “I thought, [Knopfler] is never going to write this down, and it gives me a chance to say something about him which he won’t say. He’s told the story in the songs, really, and he doesn’t need to do it any more than that.”

Illsley, born in Leicester in the English midlands in 1949, reminisces in the book about his musical education and an early job with a timber firm, before a Sociology course at Goldsmiths college brought him to London. He shared a flat with David Knopfler and writes specifically about his first meeting with David’s older brother.

“There was a man lying on the cement floor of our Deptford flat fast asleep…and his head, propped against the only chair, was at right angles to his body. The guy had an electric guitar across his chest…his face, sheet-white, revealed a hint of my flatmate David. This must have been the brother he had mentioned.”

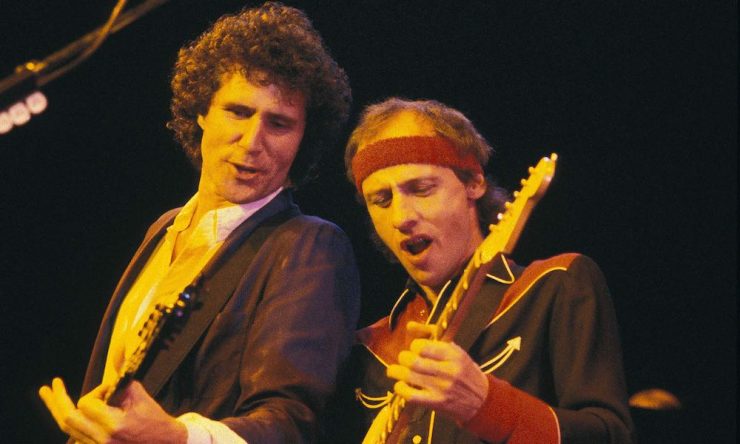

Dire Straits photo: Ebet Roberts/Redferns

Reflecting on that inauspicious introduction today, Illsley says: “I knew as soon as I met him that I was going to know about him for a long time, in one way or another. It wasn’t even a consideration about playing together at that point, I just felt this natural warmth and humor from him.

“His way of playing was very different from anything I’d ever seen, and still remains to this day,” he says. “It’s got much simpler as he’s got older, that’s for certain. Some of that playing in the early days, when you go back and look at it, was absolutely extraordinary. I took it for granted, because I grew up with it, of course. Looking back I thought ‘What a place to be, at a particular point in your life.’”

There are vivid representations of the Straits’ early struggles to be heard, including at London gigs such as the Hope & Anchor in Islington and the Rock Garden in Covent Garden, with those onerous load-ins. “We tossed a coin to see who was going to be at the top and who was going to be at the bottom, and it seemed to be just Mark and I doing it,” he laughs. “I don’t think Pick got involved and David was always doing something somewhere else. So it was left to him and I to load the bloody bass bin in. I’ll tell you what, loading it in was one thing but getting it out was another. The ceiling in the Hope & Anchor was only about eight feet high.

“I remember one evening we were playing in there, it was so packed. Hot as hell, no ventilation, everybody smoking of course. And somebody knocked the right hand side of the PA over, and nobody noticed. We suddenly realised the sound had changed a bit. I looked to my right and went ‘Oh.’ You couldn’t move. You had people about two feet away from you in those days.”

As a fledgling reporter, one of this writer’s earliest assignments was to review one of those Rock Garden gigs in late 1977, where the band were already as tight as their counterparts in their centerpiece song, “Sultans Of Swing.” Says John: “I remember sitting down with Pick and thinking I feel like I’ve been playing with this guy all my life.”

Through all those early expressions of Knopfler’s dexterity as a guitarist and writer, and David’s departure after two albums, Dire Straits expanded their horizons to filmic scale and took millions with them throughout the 1980s. “The changes were quite dramatic, from Communiqué to Making Movies,” muses Illsley. That was before Brothers In Arms reset the parameters and roared to 30 million sales. For all the glory, it was to the extreme risk of the band’s physical and mental health.

“There wasn’t much more he and I thought we could do with it,” Illsley says candidly. “To be honest after Brothers, and such a big break, I really was not expecting to do another album. That was a seminal moment in musical history, let alone just for us. 234 shows or something, and an album that still seems to capture people’s imagination, so I thought we were done.

“Then the Mandela [70th birthday concert, at Wembley Stadium] came across in 1988, and Mark and I were having lunch one day and he said ‘I’ve got some songs that I think would be great for the Dire Straits team to do. I was slightly stunned, then I thought ‘Great, here we go again.’”

The result was the 1991 swansong On Every Street, an album that is sometimes undervalued in the Dire Straits canon, but not by Illsley. “What a great album that is,” he says. “There’s some wonderful playing on it. Jeff Porcaro, mind-blowing. To get to play with these people, with Omar Hakim, and Terry Williams…talk about all your Christmases coming at once.”

But after one final tour, enough was enough. “Mark was moving off in a different direction and I completely understood that he wanted to put that machine away,” reflects Illsley. “He’d had enough of it. So we had a very open conversation before the end of the tour. I didn’t want to carry on, I wanted to do something different.”

John Illsley (far left) and band playing at the Sound Lounge in London in October 2021. Photo: Paul Sexton

And so he did, picking up from the two solo albums he had made during Straits’ shelflife (Never Told A Soul in 1984 and Glass in 1988) with a string of releases in the 2000s and 2010s, while developing his accompanying artistry as a skilled painter. All the while, Illsley has headed out on his own tours, in recent years in a Q&A format titled The Life and Times of Dire Straits, with former band co-manager Paul Cummins. That resumed with a first UK post-lockdown gig at south London’s Sound Lounge in late October, in a soldout show with esteemed guitarist Robbie McIntosh (the Pretenders, Paul McCartney, John Mayer) in the band.

Now that he’s got his story down on paper, it’s back to the future for Illsley, whose next solo set, to be titled 8 after its place in his catalog, will land in 2022 alongside an extensive British tour in April and May. But he’s happy to have put down, in his own words, what the work of a special band, and an even rarer friendship, have meant to him.

“We never did it for money, we really didn’t,” he says of his days with Knopfler and the band. “So it wasn’t a question of keeping the bank manager, or the family happy. As a consequence of that, our friendship has matured and stayed the course of time.”

Buy John Illsley’s My Life In Dire Straits.