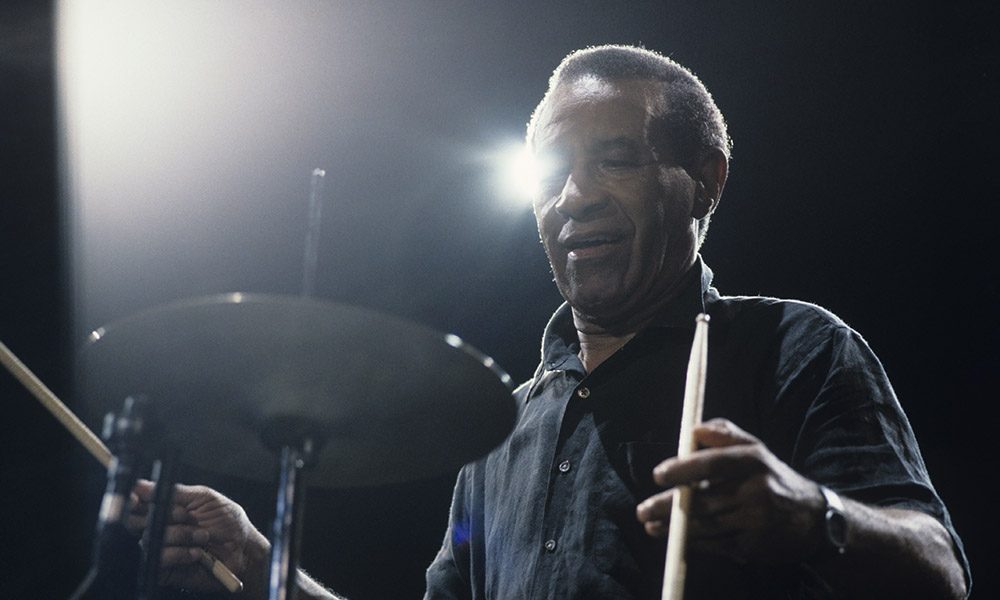

Best Max Roach Pieces: Jazz Essentials From A Legendary Percussionist

A strong case can be made for Max Roach as the most complete drummer in jazz history.

A strong case can be made for Max Roach as the most complete drummer in jazz history. Roach was in the vanguard of both the bebop movement that transformed jazz in the late 1940s and its hard-bop offshoot that galvanized the music in the mid-50s. His early 60s recordings made him a daring and distinctive artistic catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement. He was decades ahead of his time in co-founding his own record label, essentially invented the modern jazz percussion ensemble, M’boom, wrote and played music for Sam Shepherd’s plays, Alvin Ailey’s dances, gospel choirs, and hip-hop artists. He was the first jazz artist to receive the MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship in 1988. And he capped off his long and remarkable career with innovative fusions of jazz and Euro-classical music via double quartet and orchestra.

But when you take a spin with Max Roach, his august resume and place in the pantheon takes a back seat to sheer enjoyment. His musical, melodious approach to rhythm draws you in. More than a timekeeper, he was a conversationalist, fluent in a wide array of styles, settings, and tempi. Boldly open-minded, Roach was perceptive and receptive enough to be an ace collaborator, able to grasp and mold the prevailing, often daunting, visions of other artists. Roach brought out the best in Charlie Parker, cajoled Duke Ellington to be more daring and Cecil Taylor more accessible, and captured the spirit of iconoclasts like Herbie Nichols and Anthony Braxton. On his own projects, he blended fierce creativity with a love of lyrical expression, which is why his more experimental and esoteric works remained so riveting.

Listen to the best Max Roach pieces on Apple Music and Spotify.

The Birth of Bebop

Max Roach didn’t invent the modern jazz style of utilizing the ride cymbal to keep time so that the bass and snare drums could be deployed more dramatically – that would be Kenny Clarke. But the flair, imagination, and sheer technique he brought to the package was profoundly influential. There are a dozen shining examples of Roach possessing the speed, anticipation, and maneuverability required to stay astride Charlie Parker as Bird poured forth dazzling, unprecedented alto sax phrases. The audacious “Koko,” from November 1945, put bebop on the map, and Roach’s deft accompaniment highlighted Bird’s lyricism in the frenzy. Two years later, on the casually blazing “Bird Gets The Worm” in a quintet led by Bird that included Miles Davis, Roach had enhanced the agility of his stick and cymbal work – slicing, dicing, but never retarding the freewheeling pulse that made bebop sound so liberating.

Roach was initially defined by his connection to Bird, but he also enjoyed a special rapport with the pioneering bebop pianist Bud Powell. For a variety of reasons – better sound fidelity, more familiarity with bebop, a smaller ensemble, and piano instead of sax as his playmate – the clarity and innovative conception Roach brings to the Bud Powell Trio can be as impressive as his seminal work with Parker. On “Tempus Fugit” he duplicates his role with Bird as immaculate enabler, a rhythmic weather vane in Powell’s whirlwind.

The hard bop years

In an early sign of the intrepid versatility that would mark his career, Roach was one of the precious few among the core founders of the bebop revolution to embrace and then excel at its blues-oriented offshoot, hard bop. Indeed, the band he co-founded with the vibrant young trumpeter Clifford Brown might have eclipsed Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers as the premiere hard-bop ensemble had a tragic auto accident not taken the life of Brown and the group’s pianist, Richie Powell, less than three years after its formation.

The adaptation to hard bop is apparent on a 1955 cover of “Cherokee” – the song whose changes Parker used to compose “Koko” eight years earlier. Despite its blistering pace, there is an amiable warmth in Brown’s tone and phrasing, which Roach buttresses with a more lilting groove, a trademark sound that has made the Brown-Roach Quintet among the most beloved groups in jazz. Be it other covers like the sparkling “Parisian Thoroughfare” or Brown’s ode to his wife, “Joy Spring,” the ensemble was infectiously upbeat, unfurling happy music that both challenged the mind and soothed the soul. The vast majority of the group’s catalog is recommended.

Another standout selection occurred when saxophonist Sonny Rollins collaborated with the group (minus saxophonist Harold Land) for his waltz, “Valse Hot,” on the Rollins + 4 album in 1956. It’s a treat to hear Roach push and pull the ¾ time with differently timed fills in the rhythm. Four months later he would record an album’s worth of waltzes, entitled Jazz in ¾ Time. (Check out the solo near the end of “Blues Waltz.”) In the interim Brown and Powell had perished in the accident and Kenny Dorham was now on trumpet.

Roach would go on to form and play in a handful of other hard bop bands, and was crucial to such landmark late 50s albums as Miles Davis’ Birth of the Cool, and Rollins’ Saxophone Colossus. His accompaniment and solo on Rollins’ classic calypso, “St. Thomas” has to be included on any list of essential Max Roach tracks. But his partnership with Brown was the pinnacle of this phase.

Trio magic

The trio format is a venerable mainstay in jazz, but few drummers can match the elan of Roach when creating a musical milieu in this intimate setting. He transforms Bud Powell’s “Un Poco Loco,” into a personal tour de force, using a mixture of cowbell, drums, and cymbals to create distinctively different grooves on each of the three takes (all are worth hearing), providing an Afro-Cuban influence that was way ahead of its time in 1951.

The underappreciated pianist Herbie Nichols had an eccentric playing style that melded Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk and a knack for odd compositions to match. Roach does a heroic job of balancing the conceit of “The Gig” – about a band at war with itself that eventually syncs together – with the right dollop of faux-sloppiness that becomes a gateway to cooperation.

Another highlight trio selection is from the legendary 1962 Money Jungle album featuring Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, and Roach. Ellington’s “Fleurette Africaine (African Flower)” is an exquisite tone poem made more fragile by stabbing, slightly discordant note clusters from Mingus’ bass. Roach strikes the perfect balance between Ellington’s delicate recitation of the theme on piano and the aggression of Mingus, tip-toeing astride the bass with soft, pointillist beats.

We Insist! Freedom Now

In 1960, the Civil Rights Movement had begun to reach a crucial phase of effective tactics, with lunch counter sit-ins at their peak and Freedom Rides in the planning stage. Rare was the musician of any genre who stepped into this socio-political arena, but with We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, Roach and his wife, the vocalist Abbey Lincoln, each landed with both feet.

While the opening two songs, “Driva Man” and “Freedom Day,” are fairly typical agitprop, utilizing protest lyrics by Oscar Brown Jr., “Triptych: Prayer/Protest/Peace,” is something else again. The eight-minute voice-drums duet matches Roach’s incisive beats to Lincoln’s spellbinding melisma over three distinct moods and movements. The “Prayer” beseeches and the “Peace” slowly settles into place, but “Protest” is a primal purge of frustration and anger that resonates with near-equal force more than 60 years later.

The other song on the album that feels essential is the closer, “Tears For Johannesburg.” This time Lincoln’s wordless vocals backed by a nonet that includes a trio of mournful horns, and three scintillating percussionists backing Roach’s crisp ascents.

Although We Insist! was the most overt and dramatically-timed instance of Roach using his high profile on behalf of Civil Rights, it was not an isolated occurrence. Another memorable, essential song in that vein is “The Dream/It’s Time,” which opens his 1981 album, Chattahoochie Red. The first three minutes has Roach soundtracking Martin Luther King’s “I Have A Dream” speech with a solo drum fusillade that morphs into horn fanfares from the quartet as King declares “Free at last!” and the crowd roars.

The duo work

If Roach had done nothing further than help usher in the bebop movement, he would still hold an exalted place in jazz history. But more than 30 years after those seminal sessions, the now-middle-aged drummer sought out some of the most avant-garde jazz musicians on the planet for a series of stimulating, mostly improvised, duets.

Begin with the South African pianist Dollar Brand, now named Abdullah Ibrahim. The title song from the recording of their 1977 live date in New York, “Streams of Consciousness,” is 21-minute sprawl that is as much alternating solos as a duet. By contrast, “Acclamation” finds Roach uncharacteristically conservative. A happy middle ground is “Consanguinity” (defined as being from the same ancestor), which mixes solos, duets, a rousing climax, and a slow fade-in nine reverent minutes.

A year later, Roach joined the inscrutable composer and reed player Anthony Braxton in a Milan studio for seven memorably coherent and mysterious improvisations for the album, Birth and Rebirth. The best of these may be “Tropical Forest,” which has Roach tuning the drums to a saw-like twang and Braxton answering with his own quaver on clarinet before they move forward with more conventional, but still fascinating, textures. An even more adventurous follow-up album, “One in Two, Two in One,” is also recommended.

Double-album duets between Roach and saxophonist Archie Shepp in 1976 and pianist Cecil Taylor in 1979 are both acquired tastes, although it is interesting to hear Roach’s 40+ minute composition commemorating Mao’s 6000-mile trek in China on the former and Roach’s yeoman effort to slice and dice the maelstrom of Taylor on the latter (the second half of their two-part, 40-minute duet is appreciably tamer). If you are looking for a more traditional conversation, check out Roach (on brushes) and bassist Oscar Pettiford playing the standard, “There Will Never Be Another You” from 1958.

Percussion discussion

Max Roach taught American listeners that drums and percussion were not consigned to keeping time with staccato rhythms and brittle textures. As both a composer and musician, he utilized a remarkably wide spectrum of sounds, roles, and instrumentation that enabled percussionists the freedom of expression enjoyed by other frontline musicians. It is a key, enduring aspect of his legacy.

Solo drum songs by Roach were a staple of his repertoire almost from the onset of his career. The 1966 album Drums Unlimited stands out for “The Drum Also Waltzes,” the title track, and his tribute to swing drummer Sid Catlett, “For Big Sid.” Also of note: the 7-minute “Triptych,” a solo spotlight during his 1979 concert with Archie Shepp, which has the latter two songs from Drums Unlimited plus his nod to drummer Jo Jones, “Mr. Hi Hat.”

Of note from Roach’s groundbreaking percussion octet, M’boom, is a half-hour excerpt of the group playing much of the material from their debut record, Re: Percussion at an outdoor concert in 1973, which delivers a heady mix of rich melodies and jam-band freedom. So is Roach’s beautiful memorial for Charles Mingus, entitled “January V” (the date Mingus died), from M’boom’s self-titled release in 1979. It holds a delicate olio of vibraphone, marimba, tympani, Latin percussion, chimes, bells and drums. It edges out “Glorious Monster” from the same record, a very different animal with whistles and Roy Brooks going off on a musical saw.

Finally, consider a pair of Roach compositions spaced 37 years apart. The first is the Third Movement from his 18-minute opus, “Evolution,” from the 1958 recording of Max Roach with the Boston Percussion Ensemble. It shows how long he has been envisioning the compelling variety of rhythm, tone and texture that can be wrung out of a purely percussive unit. The second is “Ghost Dance,” an orchestrally-structured piece that sets Roach on trap drums amid five renowned jazz horn players, here dubbed The So What Brass Quintet. It shows that more than a half-century after the birth of bebop, Max Roach was still finding new ways to make his muse dance.

Thomas F Rowe

March 10, 2021 at 11:08 pm

Strange!!! Where is “Speak Brother Speak”???