Saint-Saëns’ ‘Carnival Of The Animals’: A Grand Zoological Fantasy

Discover the story behind Saint-Saëns’ ‘Carnival Of The Animals’, a grand zoological fantasy, featuring The Kanneh-Masons’ recording.

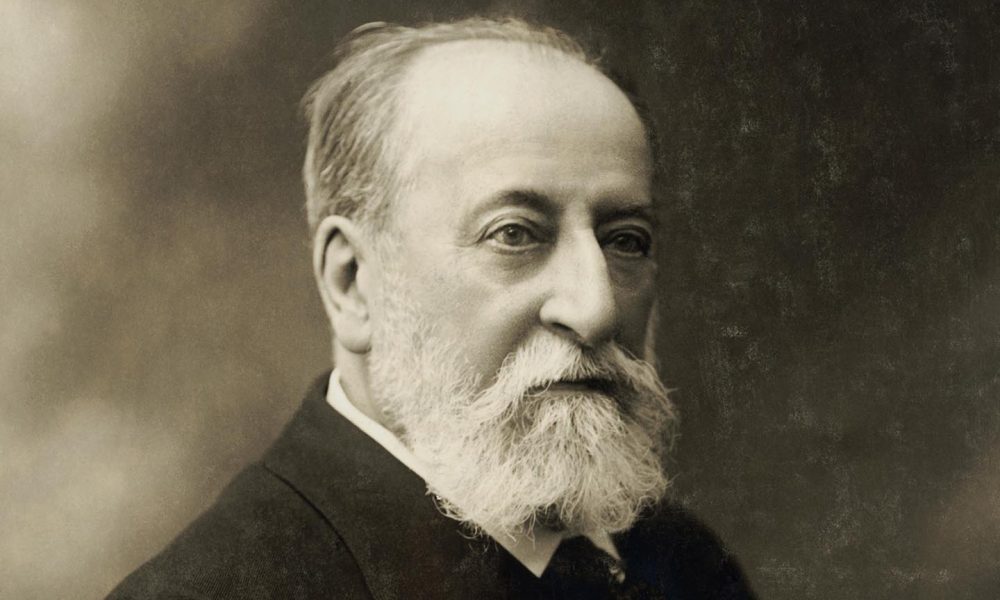

It all began with ‘The Swan’. Camille Saint-Saëns, aged 50, devised a musical portrait of the waterbird as a solo to mark his cellist friend Charles Joseph Lebouc’s retirement. But thanks to his own passion for nature, the idea gradually snowballed until it morphed into a unique grand fantaisie zoologique: a sparkling celebration of creatures great and small, full of satire, humour, mystery, imagination and even the occasional joke at the composer’s own expense. Saint-Saëns’ Carnival des Animaux (Carnival of the Animals) was born.

Listen to our recommended recording of Saint-Saëns’ Carnival of the Animals, performed by The Kanneh-Masons, on Apple Music and Spotify.

Saint-Saëns’ Carnival Of The Animals: A grand zoological fantasy

Saint-Saëns’ Carnival of the Animals was first aired in a private concert on 9 March 1886, and next in April at the salon of Pauline Viardot, the singer, composer and musical celebrity to whose feet artistic Paris flocked en masse. Here a star-studded rendition was given for an audience that included the elderly Franz Liszt, whose curiosity had been piqued. Indeed, word about the work was spreading like wildfire, inducing the shrewd Saint-Saëns to stipulate that it must only be published until after his death (except for ‘The Swan’, which was released on its own). He suspected it might prove too popular for his own good. He was right. Carnival of the Animals received its public premiere on 25 February 1922, two months after Saint-Saëns’ death, and has since become one of his best-known works.

It wasn’t as if he had written nothing else. His works encompass every genre, from 13 operas, including Samson et Dalila, and the first film score by a well-known composer (L’Assassinat du duc de Guise, 1908), down to a mini-extravaganza for a band of toy instruments entitled Les odeurs de Paris. You can appreciate he might not want all that to be overshadowed by a humourous salon work about animals.

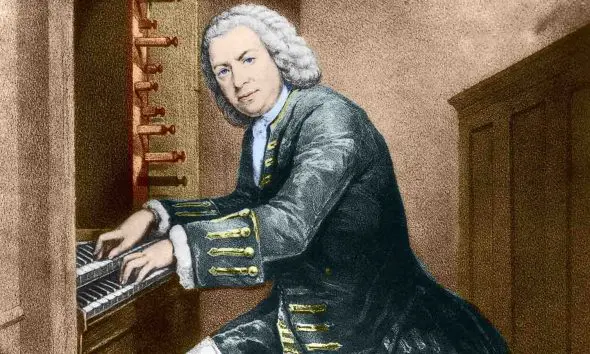

Saint-Saëns had been composing since the age of three

Saint-Saëns had been composing since the age of three. Raised by his mother and great-aunt following his father’s early death, he experienced a meteoric career as a child prodigy pianist – he once offered to play as an encore, from memory, any one of the 32 Beethoven sonatas. Nor was music enough to satisfy his mental agility: an expert mathematician, zoologist, botanist, fossil hunter and astronomer, he once used the proceeds of a bestselling piece to commission a telescope with which, from his Parisian rooftop, he examined the stars.

His life held tragedy aplenty

Nonetheless, his life held tragedy aplenty. It’s generally thought now that he was homosexual, but aged 40 he married the much younger Marie Truffot and soon had two infant sons. But in 1878, the two-year-old André fell out of the window of their fourth-floor apartment and was instantly killed. Grief-stricken, Marie was unable to feed the six-month-old baby; he was sent to her mother for care, but failed to thrive and died soon afterwards. Saint-Saëns blamed Marie. Three years later, while the couple were on holiday, he went out one day and failed to return. He never saw her again.

Saint-Saëns vanished a second time after his mother’s death in 1888 – eventually turning up under an assumed name in Las Palmas. He continued to travel extensively, particularly in north Africa; his wanderings inspired such works as his Africa Fantasy and his Piano Concerto No. 5, the ‘Egyptian’. It’s unclear whether he was trying to escape his harsh memories, or being lured by lands where he could more easily and anonymously fulfil his predilections. In his last years, despite accruing honours galore, he became a solitary, embittered individual, his days brightened only by his beloved poodle, Dalila. Perhaps it’s ironic that he ended up preferring animals to human beings.

In his philosophical tract, Problèmes et Mystères (Problems and Mysteries) he wrote: “The joys which nature gives to us and does not withhold entirely from even the most abandoned among us – the discovery of new truths, the enjoyment of art, the spectacle of suffering eased and attempts to cure it as far as possible – all these are enough for the happiness of life. One is inclined to fear that everything else is madness and illusion.”

Carnival of the Animals is a tribute to the natural world he adored

The Carnival of the Animals serves, then, as this extraordinary man’s tribute to the natural world that he adored.

The 14-movement work begins with a brief introduction, which soon brings the lion swaggering in as king of the beasts. Hens and roosters follow with some frenetic crowing, clucking and pecking, cut off by the piano as if with one swipe of a carving knife. Third, wild donkeys chase one another around the piano keyboards with exceptional fleetness of hoof.

What a change of pace: the tortoise, meandering to a sleepy version of Offenbach’s Can-Can from Orphée aux Enfers. The Elephant’s piece likewise contains a delicious musical send-up, this time the ‘Dance of the Sylphs’ from Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust, transferred to the biggest and heaviest of the stringed instruments, the double bass. It’s all mightily affectionate. Next, the kangaroos hop along rather more lightly, occasionally pausing to gaze or graze.

‘Aquarium’ is a magical seascape

‘Aquarium’ is a magical seascape, its glistening effect added by an unusual creation: the glass harmonica. Fortunately this rare instrument (like rubbing the edge of a wineglass with your finger) can be substituted by a celesta or glockenspiel. Its liquid tranquility contrasts with the spare-textured braying contest that now ensues between “characters with long ears” – as the title perhaps indicates something beyond donkeys, you can’t help wondering if Saint-Saëns is making a dig at some human equivalents.

The most mysterious movement is the Cuckoo in the wood, a distant clarinet sounding out through the shadows. The other birds, though, are chiefly confined to the ‘Aviary’, with fluttering, rustling flurries of flute and featherlight trills from the pianos.

But it’s the pianos, or the people who play them, who become the target for the composer’s most merciless lampooning. That ‘Pianists’ are included in a menagerie is indication enough – and any piano student will be sent ducking from the horrors of practising scales and exercises.

The xylophone rattles like bones in ‘Fossils’

Among Saint-Saëns’ great enthusiasms was collecting fossils, and these have a moment to themselves after dark in the museum. The xylophone rattles like bones, while the theme is a parody of Saint-Saëns’ own Danse Macabre, a virtuoso violin piece in which nocturnal devilish revelry is finally banished by dawn (the devil traditionally plays the violin – though after hearing this set he might well take up the piano instead). Night-time is indicated by a reference to the song ‘Au Clair de la Lune’.

‘The Swan’ is a gorgeous cello solo

There remains only ‘The Swan’, which started the whole idea: that achingly gorgeous cello solo drawing us back to the wonder the composer felt at the sight of natural beauty.

At last, the creatures take their bows in a final gallop, the music bounding through references to many of their different themes, rolled into one. Enough, indeed, for all the happiness of life.

Recommended recording – The Kanneh-Masons’ Carnival

The Kanneh-Masons’ first family album Carnival is very special collaboration featuring all seven “extraordinarily talented” (Classic FM) Kanneh-Mason siblings, Academy Award-winning actor Olivia Colman, and children’s author Michael Morpurgo. Carnival includes new poems written by War Horse author Morpurgo to accompany Saint-Saëns’ humorous musical suite Carnival of the Animals. The poems are read by the author himself who is joined by The Favourite actor Colman.