Best Donald Byrd Pieces: 20 Jazz Essentials From Hard Bop To Disco

The trumpeter took jazz music out of tiny clubs and up the R&B charts…and even onto the dance floor.

Donald Byrd was slick. From the high-end sports cars pictured on his album covers to his high-flying trumpet style, he represented a sophisticated, upmarket style of jazz that paved the way for much of the fusion and even smooth jazz of the 1970s and 80s. Byrd recorded some of the biggest, most popular jazz albums of all time, taking the music out of tiny clubs and up the R&B charts…and even onto the dance floor. And while carving his own path, he mentored the next generation as an educator and bandleader.

Byrd was born in Detroit on December 9, 1932. Before he graduated high school, he made inroads into the jazz scene, performing with vibraphonist Lionel Hampton’s band. He joined the Air Force, where he spent two years playing in a band, then got a bachelor’s degree from Wayne State University in Detroit, followed by a master’s from the Manhattan School of Music in New York.

A strong proponent of education throughout his life, he eventually got a Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1982. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, while recording and touring with great success, he was also a professor at various institutions, including NYU, Howard University, Oberlin College, Rutgers University, and more. He cultivated strong relationships with students, frequently helping them with their careers, and vice versa: the Mizell brothers, who produced his early 1970s albums, were students of his at Howard, and he formed a student ensemble there as well, which he dubbed the Blackbyrds. In the 80s, he formed another student group at North Carolina Central University: The 125th St NYC Band.

Listen to the best Donald Byrd pieces on Apple Music and Spotify.

Byrd’s music moved through several distinct phases. In the 1950s, he was a florid, lyrical bebop and hard bop trumpeter in the vein of Clifford Brown, Freddie Hubbard, and Lee Morgan; he made albums under his own name and worked extensively as a sideman with Art Blakey, Cannonball Adderley, Dexter Gordon, Hank Mobley, Jackie McLean, and many others. As the 1960s dawned, his music became more experimental, but he never abandoned his love of melody or his deep feeling for blues and swing. At the end of that decade, he shifted his focus to electric music, inspired by Miles Davis’s similar moves. But he was never a Davis imitator: Byrd’s version of fusion was more immediately appealing to R&B and funk audiences.

This appeal was particularly true in the early to mid-1970s, when his alliance with the Mizell brothers and a crew of accomplished studio musicians yielded actual chart hits and serious album sales. Jazz critics reviled the music, but it was a brilliant amalgam of jazz, funk, and soul, every bit as lush and beautiful as the work of Isaac Hayes, Curtis Mayfield, or the Gamble and Huff production team.

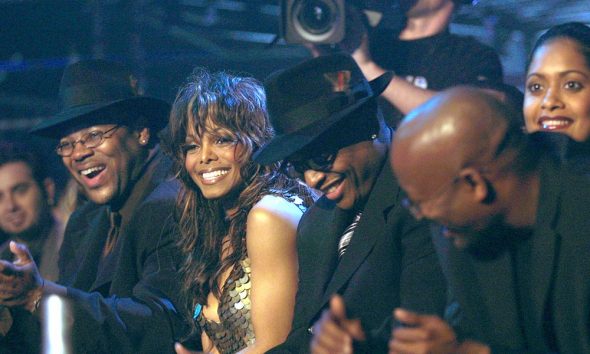

Byrd continued to record into the early 1980s, then slowed down considerably. He made a comeback on the first two volumes of Gang Starr MC Guru’s jazz/hip-hop crossover albums, Jazzmatazz and Jazzmatazz Vol. 2: The New Reality, and continued teaching until the end of his life. He died in 2013, at 80.

The list below doesn’t encompass the full breadth of Donald Byrd’s career, but it covers the significant evolutions in his work from the 1950s to the 1970s.

The Young Hard Bop Phenomenon

When he came out of the Air Force and graduated from Wayne State University, Donald Byrd moved to New York to attend the Manhattan School of Music. Before long, he was making the scene, replacing the late Clifford Brown in Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in 1955. That same year, Byrd was one of five trumpeters (the others being Ray Copeland, Ernie Royal, Idrees Sulieman, and Joe Wilder) on saxophonist/arranger Ernie Wilkins’ Top Brass album. He soloed on “Speedball,” and got a one-minute solo showcase on the ballad “It Might As Well Be Spring.”

In January 1956, Byrd joined alto saxophonist Jackie McLean’s band for Lights Out!, which also included Elmo Hope on piano, Doug Watkins on bass, and Art Taylor on drums. The opening title track starts as a late-night blues that soon picks up and becomes a hard bop fireworks display.

In the final days of 1956, Byrd was part of an all-star blowing session led by guitarist Kenny Burrell that yielded two killer albums, All Night Long and All Day Long. “All Night Long” features tenor saxophonists Hank Mobley and Jerome Richardson, with the latter man doubling on flute. Mal Waldron is on piano, and the rhythm team is Watkins and Taylor once again. A side-long track, it simmers and steams along for 17 minutes, with everyone getting a turn at the microphone.

In 1957 and 1958, Byrd worked several times with John Coltrane. The two men recorded enough material – under pianist Red Garland’s leadership, with George Joyner on bass, and, again, Art Taylor on drums – for three albums. Their version of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Woody’n You,” from Soul Junction, initially released in 1960, is a highlight.

Partnership With Pepper Adams

In 1958, Donald Byrd formed a group with baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams, a friend from Detroit. The two men cycled through multiple rhythm sections, but the material they recorded between 1958 and 1961, sometimes under the trumpeter’s name and sometimes under the saxophonist’s, was high-energy, creative hard bop. Their two voices meshed exceptionally well, with Byrd’s high-flying trumpet anchored by Adams’ rich, melodic baritone.

The title track from 1959’s Off to the Races, which features Jackie McLean on alto sax and the hard-swinging rhythm section of pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Sam Jones, and drummer Art Taylor, switches up between march time and Blakey-esque ferocity.

“Here Am I,” a Byrd original from Byrd in Hand, also from 1959, is a lush, romantic blues, on which Adams’ baritone gives the main riff a thick bottom as Charlie Rouse’s tenor sax fills in the middle. Jones and Taylor are still on bass and drums, but Walter Davis Jr. is at the piano and contributes two compositions.

Byrd and Adams made two live albums together, one under each man’s name. Byrd’s At the Half Note Café packs over two hours of music onto two CDs; “Soulful Kiddy” is a tricky but still exuberant blues.

Adams’ 10 to 4 at the 5-Spot was a more conventional blowout, with a charmingly rough and raucous live sound; “Hastings Street Bounce” is credited as a traditional tune, with an arrangement by the baritone saxophonist. Byrd makes the most of his time in the spotlight on the more than 11-minute performance.

Adventures And Explorations

The early to mid-1960s were a period of transition for Donald Byrd, as they were for jazz as a whole. His 1961 album Royal Flush was his last with Pepper Adams, but it was also pianist Herbie Hancock’s first session. The trumpeter not only included one of the youngster’s compositions (“Requiem”) but taught him to retain the rights to his publishing, helping him build the foundations of his decades-long career.

On the title track from Byrd’s next release, 1962’s Free Form, he grappled with what was then called the New Thing; joined by Hancock, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, bassist Butch Warren, and drummer Billy Higgins, they explored questing improvisation, as Higgins, who’d recently been working with Ornette Coleman, took the beat apart and went on a journey of his own.

On 1963’s A New Perspective, Byrd tried something truly adventurous with producer and arranger Duke Pearson. They paired an instrumental septet (Hank Mobley on tenor sax, Hancock on piano, Kenny Burrell on guitar, Donald Best on vibes, Warren on bass, Lex Humphries on drums) with an eight-member gospel choir – four men and four women. On “Cristo Redentor,” the singers’ ghostly moans give the music a kind of halo, as Byrd’s solo rings out like a prayer in an empty cathedral.

A New Perspective was recorded in January 1963; two months later, Byrd, Hancock, Mobley, and Warren were back in the studio with Philly Joe Jones on drums, for the first of two sessions that would make up the saxophonist’s classic album No Room for Squares. On “Up a Step,” Mobley is in a fiercer place than usual, and Byrd matches him, drawing on the blues but venturing farther out with ease.

In 1967, Byrd joined a session led by tenor saxophonist Sam Rivers, along with James Spaulding on alto, Julian Priester on trombone, Cecil McBee on bass, and Steve Ellington on drums. The music was extraordinarily raucous and free at times, which may be why Blue Note kept it on the shelf until 1975, finally releasing it as Dimensions & Extensions. Still, Byrd is as comfortable here as in any other circumstance. His solo on the opening “Precis” relies on short, punchy phrases rather than the long, lyrical lines of his earlier work, but he’s not trying on an ill-fitting hat; his creativity carries him through.

Going Electric

As the 1960s drew to a close, many jazz performers began deploying electric keyboards and adding rock-derived rhythms to their music. Miles Davis gets a lot of the credit for launching “fusion,” but Donald Byrd was right there with him. But whereas Davis opted for complex studio assemblages in partnership with Teo Macero, Byrd made his music in an old-school way, setting up a groove and riding it.

His first electric album was Fancy Free, recorded in May and June of 1969 and released in January 1970. Duke Pearson was on electric piano, with Jimmy Ponder on guitar, and Roland Wilson on bass guitar rather than upright. The four-piece horn section included Julian Priester on trombone, Frank Foster doubling on tenor and soprano saxophone, and either Jerry Dodgion or Lew Tabackin on flute, and two percussionists flanked the drums. The music was still somewhat conventional, though; “The Uptowner” is a soul jazz tune Lee Morgan could have released, with a toe-tapping groove and a typically lyrical Byrd solo.

Electric Byrd was recorded in May 1970, and released in November of that year. It featured an 11-piece band (four saxes, trombone, electric guitar, electric piano, bass, drums, and percussion) with a strong Brazilian flavor – both multi-instrumentalist Hermeto Pascoal and percussionist Airto Moreira played on the record. The opening “Estavanico” began with shimmering clouds of reverbed guitar, before moving into a slow, swaying late-night groove.

Kofi was recorded at two sessions a year apart – December 1969 and December 1970 – but not released until 1995. It’s far from a collection of leftovers, though; Byrd and his pool of collaborators from the era, including Pearson, Moreira, Foster, Tabackin, drummer Mickey Roker, and percussionist Dom Um Romão, created five highly atmospheric tracks that set and sustain a meditative mood. Byrd’s performance on the ballad “Perpetual Lover” is especially beautiful.

Ethiopian Knights, recorded in August 1971 and released the following year, moved the music onto the dance floor. Its two side-long jams (plus a three-minute ballad) offered a much harder, darker funk with deep bass from Wilton Felder, keyboards from Joe Sample (like Felder, a member of the Crusaders), and Bill Henderson III, and stinging Memphis-style electric guitar. Byrd lets the band stretch out; he’s not heard until 11 minutes into “The Little Rasti,” by which time the groove is locked-in and irresistible.

The Mizell Brothers Albums

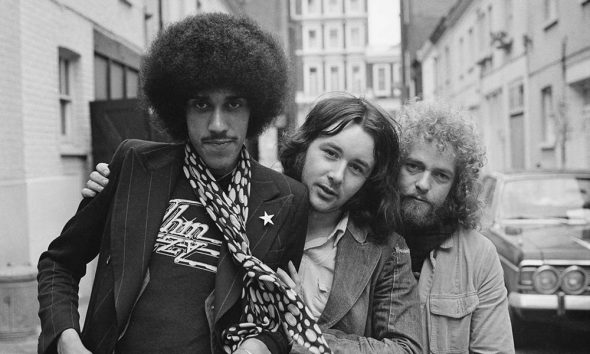

In 1972, Donald Byrd began working with brothers Larry and Alphonso (“Fonce”) Mizell, a team of producers who’d studied with him at Howard University. Fonce Mizell had also previously been part of “The Corporation,” the team that wrote and produced all of the Jackson 5’s early hits for Motown Records. They took Byrd’s music in an entirely new direction, making slick, danceable pieces that still gave him plenty of open sky to soar through.

The first Byrd/Mizell album, 1972’s Black Byrd, announced the new direction from its first track. “Flight Time” begins with the sound of a jet taking off, followed by a one-finger keyboard line, a gentle piano solo, and a lush horn fanfare. Byrd’s solo slides in like he’s dancing up to the microphone. For a while, Black Byrd was the best-selling album in Blue Note’s history, and it’s easy to hear why.

The team’s next collaboration was a little more abstract: The Mizells wrote Byrd a concept album about a prostitute. The music on 1973’s Street Lady sits comfortably alongside movie soundtracks by Marvin Gaye, Isaac Hayes, and Curtis Mayfield. Larry Mizell sings on the title track, as the large studio ensemble cranks up the funk; Byrd’s soloing is taut, but flutist Roger Glenn gets almost as much time at the microphone.

The flute was absent from 1975’s Stepping Into Tomorrow, but the vocals were even more prominent; these were basically R&B songs with trumpet solos. And that’s far from a bad thing; the Mizells were masters of slick, urbane funk. On the jazz side, saxophonist Gary Bartz proves an able front-line partner for Byrd. “Think Twice” is a competition between the vocals and the horns, and it ends up a draw.

Places and Spaces, also released in 1975, wasn’t the final collaboration between Donald Byrd and the Mizell brothers – they’d work together one more time, on 1976’s Caricatures – but the formula was starting to wear thin. On some tracks, like the single “(Fallin’ Like) Dominoes,” the trumpeter could seem like a guest on his record, struggling to pierce through the syrupy string orchestrations and the vocals. Still, the album was a hit, topping the jazz chart and hitting #6 on the R&B chart.

Think we’ve missed one of the best Donald Byrd pieces? Let us know in the comments section below.

Galinier

December 11, 2020 at 2:07 am

Hi,

I will add “Jeannine” at the half note cafe, live in 1960 : Incredible song, composed by Duke Pearson. Byrd is so amazing in that piece, his solo is mesmerizing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lrpN0-WTODs

Thanks for the article !

Gontran Galinier

Mark

February 4, 2021 at 7:30 pm

My first introduction to Donald Byrd (although I didn’t know it till much much later) was on WKRP in Cincinnati. DJ Venus Flytrap plays “Flight-time” in the “Who Is Gordon Sims” episode from 1979. Although the music isn’t identified, Venus incorporates the music as part of his patter. I always loved the music but had no idea who it was until I was able to search for it on the internet.

Billy Bandyk

February 24, 2021 at 4:02 pm

I know that it primarily refers to Donald Byrd’s solo music but what about his group The Blackbirds? “Walkin’ In Rhythm”, “Happy Music”, & “Rock Creek Park” come to mind for me (“Happy Music” displays his bop-style the best).