Jacques Brel

Widely regarded as the master of the modern ‘chanson’ genre, Jacques Brel was a highly gifted singer, songwriter, actor and film director.

Widely regarded as the master of the modern “chanson” genre, Jacques Brel was a highly gifted singer, songwriter, actor and film director whose earthy but erudite, lyric-driven songs earned him a devoted following in France and his native Belgium during his all-too-brief lifetime.

Though he passed away prematurely, in October 1978, aged just 49, Brel’s posthumous reputation has grown in stature and he is now revered the world over, his albums have sold in excess of 25 million copies globally. Though he recorded almost entirely in French (with occasional forays into Flemish or Dutch), his work has frequently been translated into English since his death. In the late 60s, Scott Walker recorded critically acclaimed covers of nine Brel songs (three apiece on his first three solo LPs, Scott, Scott 2 and Scott 3, respectively) and, over the past four decades, stars such as Frank Sinatra, David Bowie, John Denver, Leonard Cohen, Shirley Bassey and Alex Harvey have also recorded notable versions of songs from his catalogue. In 1989, meanwhile, one of his most devoted fans, Marc Almond, recorded Jacques: a 12-track LP comprised entirely of Brel-penned material.

Brel was also active behind the camera. A successful actor in French-speaking countries, he appeared in 10 films and directed two movies, one of which – the 1973 comedy Le Far West – was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the same year’s renowned Cannes Film Festival. He toured heavily worldwide – even performing concerts behind the Iron Curtain in the Khruschev-era USSR – and also wrote the critically hailed 1968 musical L’Homme De La Mancha (The Man Of La Mancha), in which he appeared as Don Quixote alongside the ill-starred Dario Moreno, who played Sancho Panza.

Brel left behind an astonishing legacy and is still being discovered by new generations of fans, yet strangely, few would have predicted he would throw in his lot with the entertainment industry when he was growing up. Born in Schaerbeek, a suburb of the Belgian capital Brussels, on 8 April 1929, Jacques’ austere father was the head of a cardboard packaging firm, Vanneste and Brel, and, as a young man, he divided much of his time shuttling between his Catholic school and a local Scout troop. He did, however, display a talent for writing at school, and began playing the guitar at 15. A year later, he formed his own theatre group, for whom he wrote plays and short stories, one of which, ‘Le Grand Feu’ (‘The Great Fire’) was published pseudonymously.

Writing and theatre began to occupy Jacques’ thoughts when he should have been studying. He failed his exams and, at 18, his father decided he should play a role in the family business. Jacques had other ideas, however, forming a local Catholic youth association, La Franche Cordée (The Rescue Party). Though primarily dedicated to philanthropic work such as fundraising events and arranging food and clothing deliveries for orphanages, the organisation also staged a number of plays (including Saint Exupéry Le Petit Prince (The Little Prince)), which Jacques was keen to support. His involvement in the association also led him to meet his future wife, Therese Michielson, better known to most as simply “Miche”.

Brel endured his compulsory military service, enrolling for two years in the army in 1948. He hated the routine but survived the experience, all the while developing a great interest in music. By 1952, he was writing his own material (the graphic, yet emotional content often appalling his puritanical family) and performing on the Brussels cabaret circuit. His big break came when he performed at La Rose Noire in Brussels. His set attracted the attention of Philips Records, the phonographic division of the Amsterdam-based electronics company, who also pressed vinyl for the Dutch arm of Britain’s Decca Records. Brel accordingly recorded his first 78, La Fire (The Fair), which impressed Jacques Canetti, Philips’ talent scout and artistic director, who invited Brel to relocate to Paris.

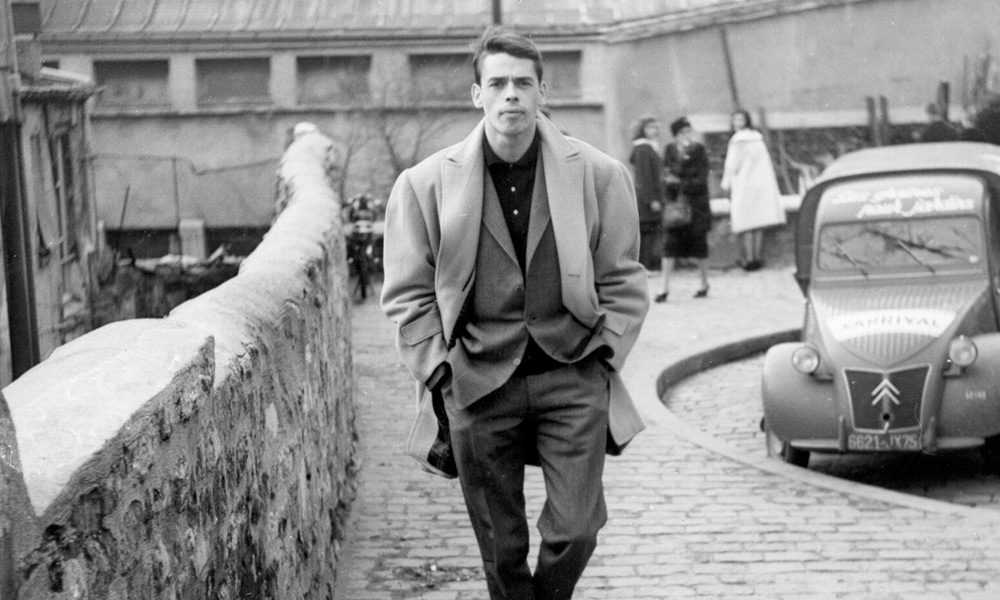

Despite objections from his family, Brel made the move in the autumn of 1953. On arrival, he grafted hard to get his name known, giving guitar lessons to help pay the rent at his digs in the Hotel Stevens, and performing on the Parisian club and cabaret circuit at venues such as L’ecluse and Jacques Canetti’s venue, Les Trois Baudets. His progression up the career ladder was initially slow, but, by July 1954, Brel had made his first appearance at Paris’ prestigious Olympia Theatre, and toured France for the first time with singers Dario Moreno, Philippe Clay and Catherine Sauvage.

Philips released Brel’s first LP in March 1954. Originally issued as the nine-song 10” LP Jacques Brel At Ses Chansons (Jacques Brel And His Songs), it was later reissued as Grande Jacques, by the Barclay label, as part of their 16-CD box set Boîte À Bonbons (Box Of Candles) in 2003. Recorded before Brel began working with regular arrangers Françoise Rauber and Gérard Jouannest, the LP was recorded live at Paris’ Théâtre De L’apollo in February 1954, and while it lacked the sweeping strings and grandeur of Brel’s later work, it was still an engaging debut.

In February 1955, Brel first met Georges Pasquier (aka Jojo), who became a close friend as well as doubling as Brel’s manager and chauffeur. His wife and family also joined him in Paris that same year (settling in the suburb of Montreuil) and, in March 1956, Brel began performing in territories outside France for the first time, appearing in North Africa, Switzerland and The Netherlands, as well as returning to the stage in Belgium. While visiting Grenoble on this trek, he met François Rauber, a highly accomplished pianist who would soon become Brel’s chief accompanist and musical arranger.

Brel made a commercial breakthrough shortly after meeting Rauber. His next 45, ‘Quand On N’a Que L’amour’ (‘When You Only Have Love’), reached No.3 on the French charts. It was reprised on his second LP, April 1957’s Quand An N’a Que L’amour (When You Only Have Love), recorded live at the Théâtre De L’apollo, with Michel Legrand and Andre Popp conducting. That same year, Brel appeared at Paris’ popular Alhambra Theatre, with Maurice Chevalier, and in November met another long-term collaborator, pianist Gérard Jouannest, with whom he would write many of his most popular songs, including ‘Madeleine’ and ‘Les Vieux’ (‘The Old Folks’).

Rarely off the road for the next few years, Brel toured Canada for the first time in 1958, the same year he released his third LP, Au Printemps (In The Spring), for Philips and, in 1959, La Valse À Mille Temps (Thee Waltz With A Thousand Beats, recorded with Rauber and his orchestra), which included two of his most enduring songs. The first of these, the desolate ‘Ne Me Quitte Pas’ (‘Don’t Leave Me’, later translated by Rod McEuan as ‘If You Go Away’), was later memorably reinterpreted by Scott Walker and Frank Sinatra, while the brooding, ruminative ‘My Death’ was also covered by both Walker and David Bowie.

Brel’s popularity reached new heights on the cusp of the 60s. By the end of the decade, he had built up a devoted following in France and had begun to perform dramatic live shows wherein he gave up playing the guitar and concentrated solely on his theatrical – and highly affecting – vocal delivery. In 1960, he also toured extensively, touching down in the US, Canada, the Middle East and returning to the USSR. His popularity surged in the US after the tour, with Columbia Records releasing a well-received compilation LP, American Debut, the tracks compiled from his quartet of LPs released in Europe.

1961 saw the release of Brel’s fifth LP, simply entitled No.5 (rechristened Marieke when reissued as part of Boîte À Bonbons). The album again included several future Brel classics, among them ‘Marieke’ and ‘Le Moribund’ (‘The Dying Man’), and Brel toured heavily to promote it, his itinerary including shows in Canada and The Netherlands. His career was already on an upswing, but he became a bona fide superstar when he headlined at Paris’ Olympia Theatre for a whopping 18 nights between 12 and 29 October 1961. Though he was originally offered the spot when Marlene Dietrich pulled out, Brel’s Olympia shows became the stuff of legend on their own terms. Fans showered him with applause every night and the critics went wild, hailing Brel as the new star of French chanson.

In March 1962, Brel left Philips and signed a new contract with Barclay, who also released vinyl by artists as diverse as Fela Kuti, Jimi Hendrix and Charles Aznavour. Brel released a string of classic albums for his new label, kicking off with 1962’s Les Bourgeois (The Middle Class), which included several evergreen classics ‘Madeleine’, ‘Le Statue’ (‘The Statue’) and ‘Le Plat Pays’ (‘The Flat Country’), the latter a tribute to Brel’s Belgian homeland.

Brel enjoyed superstar status in France for the rest of the decade. He performed another rapturously received Paris Olympia show during 1963 (where he received a standing ovation after an emotional rendition of ‘Amsterdam’), and, in 1966, released the masterful Les Bonbons (The Candles), featuring a clutch of classic tunes such as ‘Les Vieux’ (‘The Old’, later recorded by John Denver), and two songs, ‘Les Filles Et Le Chiens’ (‘The Girls And The Dogs’) and the bawdy ‘Au Suivant’ (‘Next’), which Scott Walker would cover on Scott 2 in 1968.

During the mid-60s, Brel’s popularity had also surged in the US. American poet and singer Rod McKuen began to translate his songs into English, while The Kingston Trio adapted his song ‘Le Moribund’ (‘The Dying Man’) and recorded it as ‘Seasons In The Sun’ for their Time To Think album. (This same song would later become a worldwide hit when Canadian vocalist Terry Jacks released his reinterpretation in 1974.)

Brel played a widely acclaimed show at New York’s legendary Carnegie Hall in December 1965, but, by the end of 1966, he’d tired of the endless slog of one-night stands and played a lengthy, emotional final world tour, which included high-profile shows at Brussels’ Palais Des Beaux-Arts and London’s Royal Albert Hall. He returned to New York for a final engagement at Carnegie Hall, in January 1967, and gave his very last concert in Roubaix, northern France, on 16 May 1967.

Cinema replaced film as Brel’s primary focus after he retired from the stage, though he released several more essential LPs for Barclay during the late 60s. Including ‘Le Chanson De Jacky’ (‘The Song Of Jacky’), ‘Mathilde’ and the chillingly cynical ‘Le Tango Funèbre’ (‘Funeral Tango’), 1966’s Ces Gens-Là (Those People) was crammed with classics. Ditto Jacques Brel ’67, which featured the wistful, spiralling ‘Fils De…’ (‘Sons Of…’) and 1968’s J’arrive (I’m Coming), alongside several beautifully executed tracks, among them ‘L’ostendaise’ (‘The Ostend Girl’) and the touching ‘Un Enfant’ (‘A Child’).

Brel released just two more albums during his lifetime. After re-signing with Barclay, he returned to the studio with his faithful collaborators Rauber and Jouannest, and recorded 1972’s Ne Me Quitte Pas (Don’t Leave Me), featuring spirited re-recordings of staples from his illustrious catalogue, such as ‘Le Moribund’ (‘The Dying Man’) and the oft-covered title track. Having bought a yacht, Brel then retired from music and also effectively withdrew from film after appearing in 1973’s black comedy L’emmerdeur (A Pain In The…).

After being diagnosed with lung cancer in 1975, Brel decided to live out the remainder of his life in the Marquesas Islands, in French Polynesia, renting a house in Atuona on the small island of Hive-Oa. However, with his records still selling strongly every year, Brel relented and returned to Europe to make one final album, Les Marquises (The Marquesas), in Paris, before passing away in October 1978. Eventually released by Barclay in November ’77, death’s shadow perhaps inevitably hung over many of the record’s best songs, among them ‘Vieillir’ (‘Age’) and ‘L’amour Est Mort’ (‘Love Is Dead’), but the album was – and remains – a beautifully crafted swansong.

In true showbiz style, Les Marquises’ arrival was shrouded in secrecy. Review copies were delivered to journalists in reinforced metal boxes with a timed, electronic padlock to prevent them from listening to the album before its release date. The secrecy (and total lack of pre-promotion, with no singles, airplay or interviews) only served to fuel fans’ ardour, however, and Les Marquises climbed to No.1 in France in 1978, selling over a million copies and earning platinum certification, thus ensuring that Jacques Brel remained a superstar long after he’d faced his final curtain.

Tim Peacock

Carey

November 29, 2023 at 4:11 pm

Brel wrote many great songs but he did not write The Man of the Mancha.