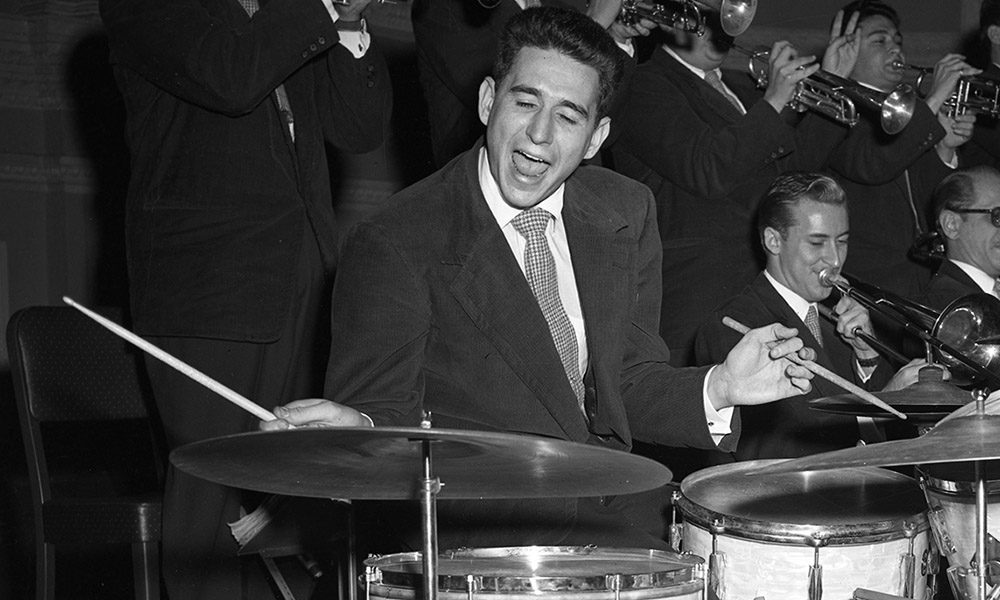

Shelly Manne, Remembering A Jazz Drumming Giant

One of the greatest jazz drummers ever, Shelly Manne appeared on countless records.

Shelly Manne was one of the greatest jazz drummers in history, appearing on more than a thousand records and enjoying a celebrated career as a Hollywood movie musician. Manne played with a dazzling array of musicians, including Bill Evans, Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie, and ran his own hip nightclub in the 1960s.

Although Manne, who was born in New York on June 11, 1920, started out playing the alto saxophone, he was destined to be a percussionist. His father Max, who produced shows at the Roxy Theatre, was an acclaimed drummer. And Max’s friend, Billy Gladstone, a top drummer in the theatres of New York, showed the young Shelly how to hold the sticks and set up a kit. “Then he put Count Basie’s ‘Topsy’ on the phonograph and, as he walked out of the room, said, ‘play!’ That was my first lesson,” Manne once recounted in the book Shelly Manne: Sounds of the Different Drummer, by Jack Brand and Bill Korst.

Although Manne was a talented runner – he was a New York City cross-country champion in high school – his desire to be a musician was sealed by a visit to Golden Gate Ballroom in Harlem to hear Roy Eldridge’s band. “I felt what they were doing so strongly that I decided I wanted to do that,” he recalled in an interview with Modern Drummer’s Chuck Bernstein in 1984.

Musical Beginnings

Manne spent his late teenage years playing for bands on Transatlantic liners. He made his recording debut with Bobby Byrne’s band in 1939. In 1942, Manne signed up for military service and assigned to the US Coast Guard Band in Brooklyn. The posting meant he was a short subway ride from the jazz clubs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Still wearing his service uniform, Manne would sit in for his drummer hero Max Roach alongside trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. He jammed with saxophone greats Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster. “Although I was in my early twenties, I looked like I was 15,” Manne recalled in Ira Gitler’s book Swing to Bop: An Oral History of the Transition in Jazz in the 1940s. “Ben used to take care of me like a guardian. If anyone offered me a drink at the White Rose Club, he’d get mad.”

After the end of World War II, Manne went on the road with Stan Kenton’s band – cutting the 1950 Capitol album Stan Kenton Innovations in Modern Music – and worked with trombonist Kai Winding and bandleader Woody Herman. He said talking to all these top musicians, including a stint on a Jazz at the Philharmonic tour with Ella Fitzgerald, was a priceless apprenticeship.

The West Coast

In 1952, Manne made the key decision of his life: he and wife Florence “Flip” Butterfield, a former dancer, relocated to California. It was there that the drummer became the leading light of the West Coast Jazz movement. He formed his own small combos, including the acclaimed Shelly Manne and his Men. “Because of my reputation, more jobs were accessible to me, so I became leader. But like most drummer-leaders, I don’t put the drums in the forefront of the group,” he was quoted in Swing to Bop: An Oral History of the Transition in Jazz.

Manne’s rendition of Bud Powell’s “Un Poco Loco“ for Contemporary in 1956, in which he played the three-minute solo with only one brush in his right hand and a small floor tom-tom drum – creating a theme-and-variation solo that cleverly leads back to the original rhythm of the piece – is considered one of the most creative drums solos of the era.

That year he also teamed up with composer André Previn to produce the first jazz album of a Broadway score. Shelly Manne and Friends – Songs from My Fair Lady became the best-selling jazz album for 1956 and included another dazzling drum solo on “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face.” The album earned Manne a Grammy nomination. “Shelly was always flawless,” said Previn. “He can sit in any rhythm section, from a trio to the biggest band, and make it swing. He is an experimenter and an innovator of the highest order.”

By this point, Manne’s reputation preceded him. Literally. After Manne’s innovative drum work lit up Peggy Lee’s hit 1958 single “Fever,” Manne was subsequently called in to play on the same song for singer Jimmy Bowen. “It actually said on my part for Jimmy, ‘play like Shelly Manne.’ So I played it just like I played it originally,” Manne recalled, in a story told in The Penguin Jazz Guide: The History of the Music in the 1000 Best Albums. “The producer stormed out of the control room and said, ‘Can’t you read English? It says ‘play like Shelly Manne.’ When I told him I was Shelly Manne, he turned and went back into the booth. I think he’s selling cars now.”

Manne’s collaborations are too numerous to list in full. It’s a veritable who’s who of the era: Lalo Schifrin, Ornette Coleman, Chet Baker, or Mahalia Jackson. Explaining his philosophy, Manne said that “when I play with [keyboard player] Teddy Wilson, I don’t play the same as I would with Dizzy Gillespie. It’s a matter of listening, knowing the music, and how to play a particular style, feeling, and the energy level. You have to be able to adapt.”

The Film Industry

His ability to tailor his skills to the job made him a favorite with Hollywood. In 1954, Manne was hired to play some “complicated” things for Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window. “Shelly just sat down, read them off, and played them perfectly,” said orchestra contractor Bobby Helfer in Drummin’ Men: The Heartbeat of Jazz, The Swing Years, by Burt Korall. Manne can be heard on the soundtrack of classics such as Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Some Like it Hot, and Doctor Zhivago.

His adventures in film didn’t stop there. Manne advised Frank Sinatra on drumming technique for his role in The Man with the Golden Arm and got his own chance to shine in front of the camera when he acted in the Oscar-winning 1958 picture I Want to Live! and The Gene Krupa Story.

The Jazz Club

By the end of the 50s, Manne was looking to expand past simply playing on records and soundtracks. In 1959, during a tour of Europe, he dropped into the newly-opened Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London. “I’m pretty certain that Shelly’s enthusiasm for the club’s atmosphere prompted him to open his Manne Hole Club,” Scott wrote in his memoir Some of My Best Friends are Blues.

Manne opened his Los Angeles club in the summer of 1960. The diner, near Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard, had photographs and album covers on the walls and an illuminated drumhead above a sign saying “Shelly Manne: Founder and Owner, 1960 A.D.” Over the next 12 years, this crowded, smoky club became a magnet for jazz greats including John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Elvin Jones, and Thelonious Monk. Manne played there most weeks, ending sets by modestly exclaiming, “Do I sound O.K.?”

The Later Years

Manne continued to work hard in the 1970s and 1980s – he branched out and appeared on two albums with Tom Waits and, along with Gerry Mulligan, one with Barry Manilow – and said that late in life he enjoyed most playing in a small trio, explaining to Drummer Magazine that it was “because I guess now that I’m getting older, my hands get a little tired.” His wife later revealed to the Percussive Arts Society website that “just before his death he remarked that there were so many new young lions playing drums, he didn’t think anyone knew who he was any more.”

On September 9, 1984, he was honored by Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley and the Hollywood Arts Council, who declared it Shelly Manne Day. Sadly, just a few weeks later, the 64-year-old suffered a heart attack at home and died on September 26 at Serra Medical Clinic. Manne was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in the Hollywood Hills. Every musician at his funeral had personal tales of his wit, remarkable generosity, and kindness.

Yet for all his fame and fortune, the drummer was happiest simply playing jazz. “All I cared about was swinging,” Manne said in the Modern Drummer interview three months before his death. “That’s the one thing I felt inside my body from the moment I started playing – the feeling of swing, the time, and making it live.”

Listen to a West Coast Jazz Essentials playlist on Apple Music and the best of Shelly Manne on Spotify.

Peter Robinson

June 17, 2020 at 11:04 am

An excellent summation of Shelly’s career. I had the pleasure of meeting him in London on two occasions. By the way,his recording of Un Poco Loco was recorded for Contemporary Records, not Concord. Regards, Peter Robinson

Todd Burns

June 11, 2021 at 6:03 pm

Thanks for the correction, Peter! We’ve amended that in the text now.

john atkinson

June 13, 2022 at 10:55 pm

Anybody checked in on Flip? I got to sit with her at a John LaBarbera show.

Geof Foote

September 4, 2022 at 9:03 am

His recordings with Barney Kassel were epic!! obrigado para issto historia…

MARVILLOSA!!!