The Clash

When it comes to exuding timeless rock’n’roll cool, few bands will ever match The Clash. Fiery, politicised and utterly mandatory, the West London quartet were often dubbed ‘The Only Band That Matters’.

When it comes to exuding timeless rock’n’roll cool, few bands will ever match The Clash. Fiery, politicised and utterly mandatory, the West London quartet were often dubbed “The Only Band That Matters”, and though they eventually split in some disarray in 1985, their invigorating catalogue has continued to inspire new generations of fans.

Ironically, though, while The Clash (and their punk peers Sex Pistols) are now revered rock icons, they initially set out to destroy rock: albeit what they saw as the bloated, prog-dominated version of what passed for the mainstream rock’n’roll scene during the mid-70s.

Rockabilly-loving frontman Joe Strummer’s rudimentary guitar style had already earned him his chosen nom de guerre while he was busking on the London Underground. Born John Graham Mellor, he was the son of a Foreign Office diplomat, but from 1974 he’d been eking out a living in a variety of London squats and fronting hotly-tipped London R&B outfit The 101’ers.

However, when the already controversial Sex Pistols supported The 101’ers at a show at The Nashville Club in Kensington, in April ’76, Strummer immediately felt the wind of change. As he later recalled in the acclaimed, Don Letts-directed Clash documentary Westway To The World: “after just five seconds [of the Pistols’ set], I knew we were yesterday’s papers”.

Strummer quickly connected with like-minded new collaborators Mick Jones and Paul Simonon. Formerly a Mott The Hoople devotee, lead guitarist Jones had been involved in proto-punk outfit The London SS during 1975, and while that band never got beyond the rehearsal stage, their on-off personnel also included future members of The Damned and Generation X. Reggae fanatic-turned-budding bassist Simonon first encountered Jones when he tried out as vocalist for The London SS, but while he failed the audition, he cemented a friendship with Jones.

Turned on by the possibilities of punk, Strummer, Jones and Simonon formed The Clash during the early summer of ’76, with Strummer and Jones quickly developing a writing partnership. The duo took to heart a brief from their enigmatic manager Bernard Rhodes, who suggested they eschew writing about love in favour of penning short, sharp, socially aware songs such as ‘Career Opportunities’ and ‘Hate And War’, which dealt with wider issues including unemployment and the UK’s political climate.

Initially going out as a quintet (augmented by drummer Terry Chimes and future PiL guitarist Keith Levene), The Clash duly played their first gig supporting Sex Pistols at Sheffield’s Black Swan on 4 July 1976, and continued with a series of fanbase-building shows including a critically acclaimed performance at London’s 100 Club Punk Festival on 21 September.

After Levene and Terry Chimes departed, The Clash (with stand-in drummer Rob Harper) appeared at the handful of shows which went ahead on Sex Pistols’ notorious Anarchy Tour of December ’76. By this time, the first British punk singles, including The Damned’s ‘New Rose’ and the Pistols’ ‘Anarchy In The UK’, had appeared on vinyl, yet The Clash remained unsigned until 25 January 1977, when they finally inked a deal with CBS in the UK and Epic in the US.

With the band’s live soundman Mickey Foote producing and Terry Chimes temporarily back on drums, The Clash recorded their debut LP in short bursts over three weekends in February ’77. Preceding the LP’s release, though, was the band’s debut single, ‘White Riot’ – a commentary on 1976’s riot-strewn Notting Hill Carnival – which rose to No.38 in the UK Top 40 despite only minimal airplay.

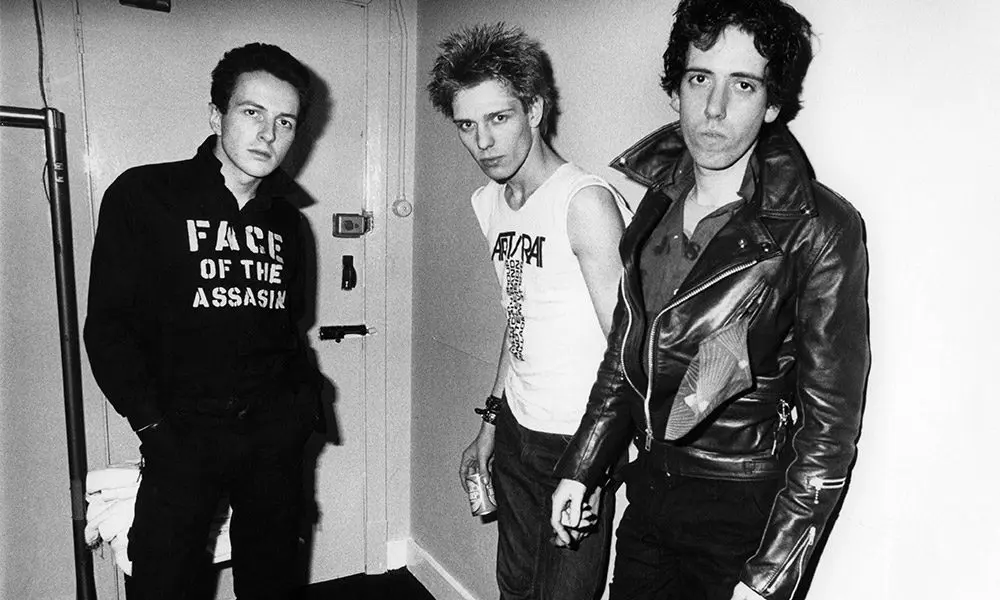

Housed in a memorable monochromatic sleeve featuring the menacing-looking trio of Strummer, Jones and Simonon standing on the trolley ramp of the old Tack Room opposite their rehearsal studio in London’s Camden Town, The Clash’s self-titled debut LP was released on 8 April. The music it contained was raw, intense and vital. Songs such as ‘London’s Burning’, ‘I’m So Bored Of The USA’ and ‘Remote Control’ railed relentlessly against the alienation and despair of the times, though the band also pulled off a major coup with their militant – and highly credible – reinvention of Junior Murvin’s reggae hit ‘Police And Thieves.’

The Clash attracted rave reviews, with the NME’s Tony Parsons hailing it as “some of the most exciting rock’n’roll in contemporary music”. The LP subsequently climbed the UK charts, peaking at No.12 en route to going gold. Following its release, The Clash’s classic line-up finally fell into place when versatile, jazz-trained drummer Nicky “Topper” Headon was recruited in time for the nationwide White Riot UK Tour of May ’77: an excursion which included a riotous, sold-out date at London’s cavernous Rainbow Theatre.

The Clash’s second LP, Give ’Em Enough Rope, was presaged by three classic, non-LP singles bridging 1977-78. Though its scathing lyric lambasted managers, record companies and the sorry state of punk, the furious, Lee “Scratch” Perry-produced ‘Complete Control’ rose to No.28. February ’78’s tight, taut ‘Clash City Rockers’ also cracked the UK Top 40, while ‘(White Man In) Hammersmith Palais’ was another masterful blend of polemically inclined punky reggae which hit a disappointingly meagre No.32.

Overseen by Blue Öyster Cult producer Sandy Pearlman, the studio sessions for The Clash’s second full-length LP, November ’78’s Give ’Em Enough Rope, were protracted and reputedly arduous for the band. However, they eventually emerged victorious with a powerful, mainstream-inclined rock album which included their first UK Top 20 hit (the aggressive, Middle Eastern terrorism-related ‘Tommy Gun’) and evergreen live favourites including ‘Safe European Home’ and Mick Jones’ atypically tender ‘Stay Free’.

Critics, including Rolling Stone’s highly respected Greil Marcus (who praised the LP’s “accessible hard rock”), greeted Give ’Em Enough Rope warmly. With the album peaking at No.2 in the UK (and earning another gold disc), The Clash celebrated with a prolonged bout of touring. In the UK, the band’s lengthy Sort It Out tour straddled the Christmas period before they set out on their first US jaunt during February 1979.

The Clash entered London’s Wessex Studios with co-producer Bill Price prior to the US sojourn, and a productive session yielded their next record, the Cost Of Living EP, released in the spring of ’79. Headed up by a rousing cover of the Bobby Fuller Four’s 1966 hit ‘I Fought The Law’, the EP provided the band with another Top 30 hit while they began working up material for their next LP.

Sessions for The Clash’s third LP, London Calling, again took place at Wessex across the summer of 1979. Mercurial ex-Mott The Hoople producer Guy Stevens manned the desk and the band loved the brilliantly bizarre methods he employed to capture the vibe, including pouring beer into pianos and physically scrapping with co-producer Bill Price.

Prior to the release of London Calling, The Clash embarked on their high-profile Take The Fifth US tour, which included gigs at the old Monterey Festival site in California and New York’s prestigious Palladium Theatre. Towards the end of the incendiary NYC show, photographer Pennie Smith captured an in-the-zone Simonon smashing his bass to smithereens: her iconic image later adorned the cover of London Calling.

An invigorating call to arms, London Calling’s strident titular song provided The Clash with a No 11 UK hit and its parent album arguably remains the pinnacle of the band’s achievements. Though it also featured hard-driving anthems such as ‘Clampdown’ and ‘Death Or Glory’, London Calling killed off any remaining notions that The Clash were simply a “punk” band. Indeed, the LP found the group communing with everything from reggae (‘Guns Of Brixton’) to New Orleans-style R&B (‘Jimmy Jazz’) and sunny ska-pop (‘Rudie Can’t Fail’), and making it all sound utterly life-affirming.

London Calling attracted widespread acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic, with Village Voice critic Robert Christgau describing it as “the best double-album since The Rolling Stones’ Exile On Main Street”. The LP also sold in droves, peaking at No.9 (and going double-platinum) in the UK and rising to No.27 on North America’s Billboard 200.

Despite the adulation, The Clash had no intention of resting on their laurels. They scored another UK hit in the summer of 1980 with the lilting, reggae-flavoured ‘Bankrobber’ and, during breaks from touring the US and Europe in support of London Calling, booked studio time in New York and London. This feverish activity resulted in the band’s ambitious fourth LP, Sandinista!, which was released in time for Christmas 1980.

This challenging triple-disc set (sold for the price of a single album), was a 36-track, “White Album”-esque sprawl wherein The Clash got to grips with everything from dub to folk, and jazz to Motown-esque pop, while two of its stand-out cuts, ‘The Magnificent Seven’ and ‘Lightning Strikes (Not Once But Twice)’, also incorporated elements of the new hip-hop sound then beginning to emerge in New York.

Sandinista!’s dizzying array of styles divided the critics, but the record sold solidly, peaking at No.19 in the UK and No.24 in the States, and yielding gold discs in both territories. The Clash continued to build on their burgeoning Stateside popularity during 1981 when, across May and June, they played an unprecedented run of 17 shows at New York’s Bond’s Casino on Times Square. After further high-profile European residencies in Paris and a seven-night run at London’s Lyceum Theatre, the band returned to New York, where they decamped to Electric Lady Studios to record their fifth LP, Combat Rock.

The Combat Rock sessions again produced enough material for a double-album but, after producer Glyn Johns (The Who, Faces) was drafted in to mix and edit, the album was eventually issued as a more user-friendly single disc in May 1982. Veering wildly from the brittle, militant rockabilly of ‘Know Your Rights’ to the angular ‘Overpowered By Funk’ and the tense, Allen Ginsberg-enhanced ‘Ghetto Defendant’, the absorbing Combat Rock was experimental in design, yet it included two sure-fire hits courtesy of Mick Jones’ infectious rocker ‘Should I Stay Or Should I Go’ and the club-friendly ‘Rock The Casbah’, composed chiefly by Topper Headon.

Both these cuts went on to become US Top 20 smashes, and the well-received Combat Rock took The Clash to the brink of superstardom, going gold in the UK and Canada and double-platinum in the US. However, just as the band had the world at their feet, things began to unravel. Topper Headon, who had been struggling with drug-related issues for the past 18 months, was fired just as the Combat Rock UK tour was due to kick-off; The Clash were forced to rehire Terry Chimes to complete their touring commitments during the latter half of 1982.

With the freshly recruited Pete Howard replacing the departing Chimes, The Clash headlined the opening night of Los Angeles’ enormous Us Festival on 28 May 1983, but it proved to be their last major hurrah. In September that same year, internal disagreements within the band came to a head and The Clash’s primary musical architect, Mick Jones, also left the fold.

In hindsight, Joe Strummer frequently acknowledged that the sackings of Headon and Jones were terrible mistakes. In Pat Gilbert’s Clash biography, Passion Is A Fashion, Strummer willingly conceded that the group was “limping to its death from the day we got rid of Topper”. At the time, however, a Mk II version of The Clash, with Strummer, Simonon and Pete Howard joined by guitarists Nick Sheppard and Vince White, regrouped to tour and record a final LP, Cut The Crap, in 1985.

Despite its unfortunate title, this much-maligned album nonetheless went gold in the UK and contained one last great Clash Top 40 hit courtesy of the impassioned ‘This Is England’. By the end of the year, however, The Clash were no more, though Mick Jones and Joe Strummer went on to release excellent post-Clash material (with Big Audio Dynamite and The Mescaleros, respectively) and they enjoyed an onstage reunion just weeks before Strummer’s tragically premature death in December 2002.

The Clash’s profile has remained high since their demise. London Calling frequently in the upper echelons of most music publications’ Greatest Rock Albums listings, while, 25 years after its release, London’s The Times dubbed the group’s eponymous debut “punk’s definitive statement” alongside Sex Pistols’ Never Mind The Bollocks… Here’s The Sex Pistols. Diligently assembled retrospectives of the band’s career, ranging from 1988’s The Story Of The Clash Vol.1 through to 2013’s exhaustive 12CD Sound System have ensured their oeuvre remains in the public eye, while a wealth of seismic artists, from U2 to Rancid, Manic Street Preachers and LCD Soundsystem, have all cited this phenomenal quartet as the catalyst for starting riots of their own.

Tim Peacock

David

November 19, 2021 at 11:08 pm

The only band that matters when there were literally hundreds of bands (at least) in the same league as Clash, well,… :DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDwhaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaat?????????????!!!!!

Salem Leo

May 2, 2023 at 11:45 pm

GG Allin makes the Clash look like a bunch of little girls singing Twinkle Twinkle Little Star to their Disney princess dolls.