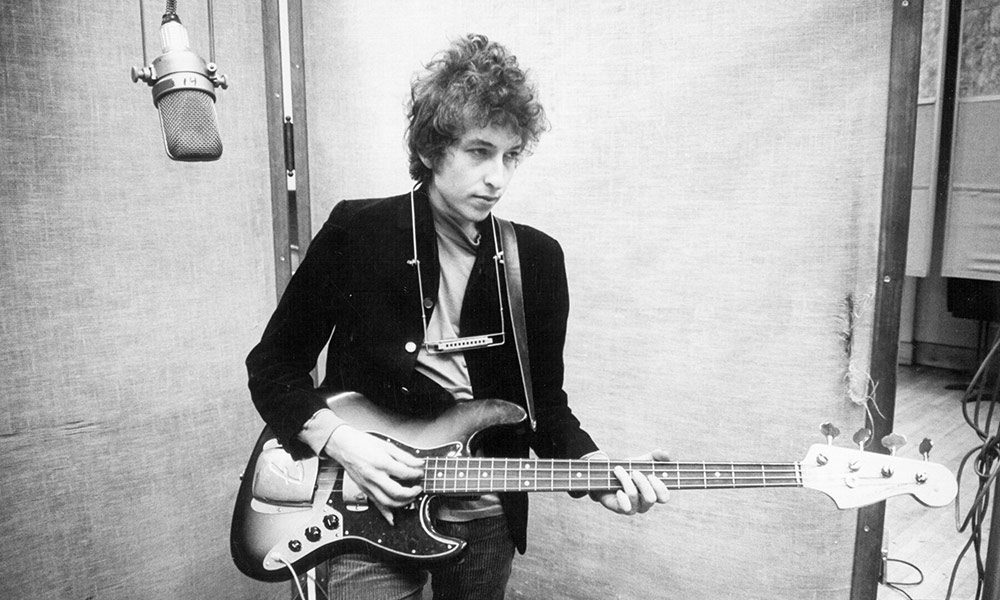

Bob Dylan

A major voice and arguably the most distinctive of all American artists in the post-Elvis Presley era, Bob Dylan’s work has inspired, delighted, perplexed and divided opinion over six decades of recording and touring.

A major voice and arguably the most distinctive of all American artists in the post-Elvis Presley era, Bob Dylan’s work has inspired, delighted, perplexed and divided opinion over six decades of recording and touring. Along the way his notable work includes The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, the masterpiece double-album Blonde on Blonde, the seminal early 70s album Blood On The Tracks and 1997’s Time Out Of Mind.

A chronicler of civil rights and anti-war protest folk in the early 60s, Dylan assumed the mantle of spokesman for his generation, an accolade he only briefly embraced, preferring to widen his horizons as he moved into electric folk, country music and traditional American music in its broadest sense, be that in the spirit of Hank Williams or Frank Sinatra. Though he doesn’t profess to own the Great American Songbook, Dylan enriches the form.

Often at his best when seemingly being most capricious, this is a man who swum against the tide in the mid-60s when he insisted on his right to work with musicians such as Mike Bloomfield, The Band and the Nashville A-team, as well as side trips with his old friends Grateful Dead, Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers, and George Harrison in The Traveling Wilburys. His Never Ending Tour means that while he’s seldom available to the media, he is often within touching distance of his fans. Among his many accolades are 12 Grammy Awards, one Academy Award and the 2016 Nobel Prize In Literature. Though he refused to accept in person, Dylan sent a gracious speech stating, “I too am often occupied with the pursuit of my creative endeavours.” Amen to that.

Born Robert Allen Zimmerman, on 24 May 1941, in Duluth, Minnesota, the young Bob was a rock’n’roll fanatic who moved into folk in order to mine deeper, darker moods. After becoming a hit on the coffee house circuit in Minneapolis, he moved to New York City in 1961 and made contact with his idol and early muse Woody Guthrie. Tapping into a scene popularised by Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Dylan played the clubs in Greenwich Village and shared digs and stages with Dave Van Ronk, Fred Neil, Karen Dalton, Odetta and the Irish musicians The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem.

Signed to Columbia by John Hammond, who produced his self-titled debut album in 1962, Dylan’s voice was generally heard for the first time on a collection of folk standards with the inclusion of two originals, ‘Talkin’ New York’ and ‘Song To Woody’. That promising start was eclipsed completely by The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, which was produced by Hammond and Tom Wilson in New York, and released in May 1963. The young talent was beyond precocious: ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’, ‘Girl From The North Country’, ‘Masters Of War’, ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’ and ‘Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right’ announced the arrival of a major star. Such was his popularity, Dylan could have stood for President.

The starker The Times They Are A-Changin’ hinted that he wasn’t going to be pigeonholed for long by the folk purists and Another Side Of Bob Dylan upped his game with a set of songs that reached The Byrds in Los Angeles, who covered ‘All I Really Want To Do’ and used it as the template for their own newly minted jingle-jangle folk-rock.

Feeling empowered by his status, Dylan dropped Bringing It All Back Home in 1965, distanced himself from sheer protest and began his electric odyssey. He was credited with influencing The Beatles, and songs such as ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’, ‘Maggie’s Farm’, ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ and the epic ‘It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)’ made an amazing difference to the development of popular music on both sides of the Atlantic. The same went for Highway 61 Revisited, whose opening cut, ‘Like A Rolling Stone’, and closing magnum opus, ‘Desolation Row’, altered the boundaries of rock forever, often thanks to a cast including Al Kooper on organ and piano, Bloomfield and country master Charlie McCoy on guitar, plus a tough electric rhythm section, all expertly manhandled by Dylan’s new producer, Bob Johnston.

A move to Nashville – with forays back to New York – gave us Blonde On Blonde, whose 14 songs defined the summer of ’66 without paying any lip service to swinging LSD scenes or hippified mantras. Instead, there was a unique blend of everything he could do, from writing hits such as ‘Rainy Day Women #12 and 35’ and ‘I Want You’ to penning more testing work such as the emotionally coruscating ‘Visions Of Johanna’ and the visceral ‘“Just Like A Woman’.

Dylan’s reputation as the bard of beat grew exponentially thereafter when he returned to rootsier fare on John Wesley Harding, a country masterpiece on which ‘All Along The Watchtower’ slipped through like a neutron bomb while ballads and ditties in the old troubadour fashion drew fulsome praise and helped remove the prejudice to country music.

A new-sound crooning Bob popped up on Nashville Skyline: he duetted with Johnny Cash on a revisit to ‘Girl From The North Country’ and opened his heart on the bittersweet ‘I Threw It All Away’. Evidently acutely aware of his own image, Self Portrait (1970) could be construed as a deliberate attempt to loosen the shackles of superstardom with four sides of covers and originals designed to appear like a bootleg recording (this being the heyday of illicit releases). Much of it sallied over the heads of critics but takes on Gordon Lightfoot’s ‘Early Morning Rain’, Paul Simon’s ‘The Boxer’ and the Bryant Brothers’ ‘Take A Message To Mary’ had serious intent even if the overall mood was deliberately playful.

The excellent New Morning, containing ‘If Not For You’ (which George Harrison covered on All Things Must Pass, though Olivia Newton-John made it a hit single in 1971), prefaced a new chapter. It was followed, three years later, by the soundtrack album Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid, which included the relaxed soon-to-be-standard, ‘Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door’.

Dylan then reunited with his Canadian chums The Band for the studio outing Planet Waves and its attendant live album, Before The Flood. Touring with the group that had backed him on his incendiary 1966 live shows rejuvenated Dylan’s live appeal, drew critics back on board and paved the way for 1975’s Blood On The Tracks, his most poetic if not entirely autobiographical work; despite some oddly lukewarm responses at the time, it has become many people’s go-to Bob Dylan album. The writing is so deft and the imagery so lucid that songs such as ‘Tangled Up In Blue’, ‘Simple Twist Of Fate’ and ‘Lily, Rosemary And The Jack Of Hearts’ stand beyond the remit of lesser mortals. Producing the record himself, Dylan added mandolin and organ to his repertoire and also turned in some of the most unforgettable vocals of his career. Never ceasing to please and amaze, the album now consistently wins five-star plaudits.

The worked-over official release of The Basement Tapes (cherry-picking from a heavily bootlegged set of sessions) captured a narrative strain and a roots-rock sensibility. Good as it was, however, the arrival of Desire, which featured stand-out cuts ‘Hurricane’ and ‘Joey’, plus vocal assists from Emmylou Harris and Ronee Blakley, found the artist back in love with the road, setting out across the States on the Rolling Thunder Revue, and capturing a later show on the Hard Rain album.

1978’s Street-Legal and the following year’s Slow Train Coming found Dylan at a crossroads, depicting a man torn between secular and religious motifs. Born again in 1980, Saved moved into gospel terrain and Old Testament fire-and-brimstone before 1981’s Shot Of Love, which included the superlative ‘Every Grain Of Sand’ and remains one of Dylan’s personal favourites.

Infidels (1983) was less favourably received, but by now Dylan was used to being praised and pilloried by rote, so that when he made Empire Burlesque, which featured various Heartbreakers, reggae stalwarts and rock drum legend Jim Keltner, and was mixed by pioneering hip-hop producer Arthur Baker, one senses he could care less. But the consensus turned back in his favour once the career-spanning box set Biograph reminded us all why we’d loved Dylan in the first place. 1986’s Knocked Out Loaded passed muster with Petty in the mix, but Down In The Groove and Dylan & The Dead were less essential.

Oh Mercy and Under the Red Sky tipped the session player balance without thrilling unduly. However, The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991 got the archivists frothing: there would be more in this vein, but not before 1992’s Good As I Been To You and the following year’s World Gone Wrong revisited the folk originals Dylan had cut his teeth on. 1993 also saw the live 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration, which allowed him to enjoy the limelight on stage with pals Willie Nelson, Eric Clapton, Lou Reed, George Harrison and Neil Young (who dubbed the event “Bobfest”).

If he’d struggled to retain his voice throughout the changing times of the 80s, Dylan quashed doubts with 1997’s Time Out of Mind, on which songs such as ‘Cold Irons Bound’ and ‘Standing In The Doorway’ reminded us of an immense presence. Several archival compilations and box sets in The Bootleg Series followed before Love And Theft (produced by Jack “Bob Dylan” Frost) broke the ice and introduced his new touring band, including Larry Campbell, Charlie Sexton, Tony Garnier and David Kemper.

Recorded as he approached 65, Dylan was back in the main news again with 2006’s Modern Times. Closer, ‘Ain’t Talkin’’ was a revelation in terms of spiritual blues-noir. Folks will worry on behalf of a much-loved artist, but Dylan was in form and ready to hit the studio again for 2009’s Together Through Life, on which he collaborated with Jerry Garcia’s old sparring partner Robert Hunter.

After a quick detour into seasonal classics on Christmas In The Heart, Dylan’s magical allure was undimmed on 2012’s Tempest (which included the John Lennon tribute ‘Roll On John’) and emerged brightly again on 2015’s Shadows In The Night, a collection of songs Sinatra had mastered. As Dylan saw it: “I don’t see myself as covering these songs in any way. They’ve been covered enough. Buried, as a matter a fact. What my band and me are basically doing is uncovering them. Lifting them out of the grave and bringing them into the light of day.”

Hot on its heels was the similarly focused Fallen Angels, performed in the sentimental mood of the 20th-century American score and libretto chiefs the likes of Jimmy Van Heusen and Harold Arlen. Vastly influenced by his old friend Willie Nelson’s Stardust epic, Dylan wraps up some loose ends as if to say, “I’ve given you many of my best shots, and this is what I love to listen to.”

The revelations keep coming. On 2017’s Triplicate, Dylan casts his net even wider for a triple-disc, 30-song album that takes in little works of art from a variety of American songwriters. Don’t try to guess what comes next. Bob Dylan’s next dream could be a nightmare, maybe a rousing epiphany. He’s one of rock’s stalwarts, but he remains forever young.

Max Bell

Ken Speed

August 7, 2022 at 4:24 pm

If not for you was co-written with George Harrison.

Their joint recording efforts never came to anything

but Harrison’s version on All Things Must Pass is

based on the version on their joint session while Bob as usual opted for something entirely different.

Oh Mercy is a wonderful album. Some truly beautiful songs.

Arguably it’s his best produced thanks to Daniel Lanois.