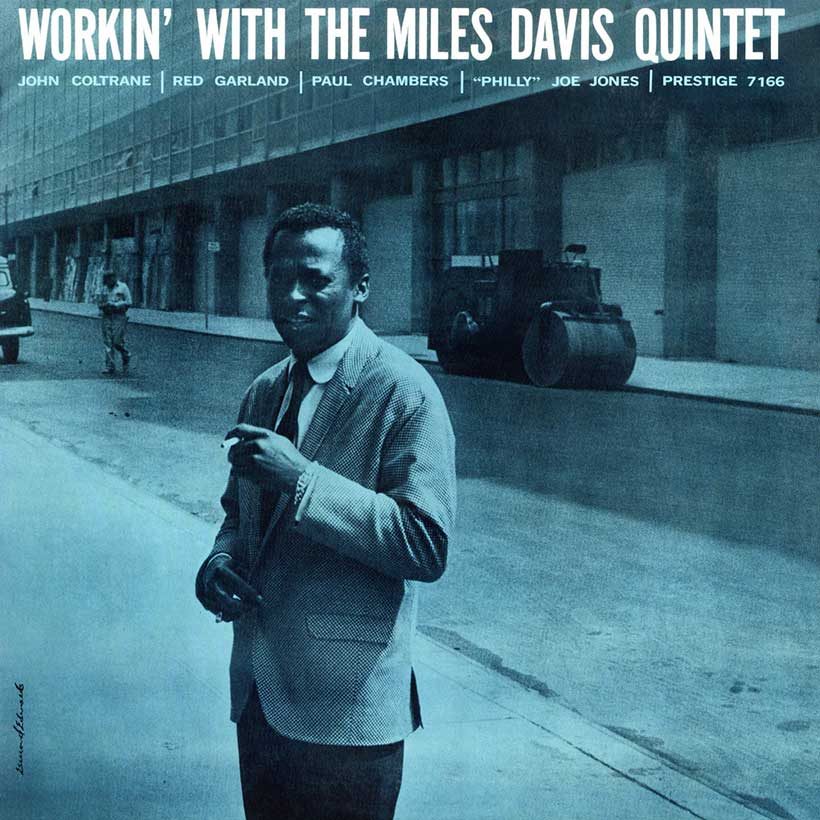

‘Workin’ With The Miles Davis Quintet’: A Job Lot Of Post-Bop Brilliance

Profoundly exploratory, ‘Workin’ With The Miles Davis Quintet’ proved that Miles Davis assembled one of the most progressive groups in jazz.

In his desire to leave the jazz indie label Prestige and join the affluent major Columbia, for a lucrative recording deal that would eventually establish him in the mainstream as a household name, Miles Davis agreed to stockpile several albums’ worth of material for producer Bob Weinstock’s small company, thereby fulfilling his contractual obligations. Though recorded quickly over just two sessions, the resulting albums – Cookin’, Relaxin’, Workin’ and Steamin’ With The Miles Davis Quintet – remain key post-bop albums and a fascinating look at Miles’ earliest recordings with his first great quintet.

Listen to Workin’ With The Miles Davis Quintet on Apple Music and Spotify.

One of the most progressive groups in jazz

At the time of their recording, the trumpeter was leading one of the most progressive and exciting small groups in modern jazz, which he had been developing with a successful residency at the Café Bohemia venue in New York: a quintet comprised of tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, pianist William “Red” Garland, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Philly Joe Jones. The group had secretly started recording their first album for Columbia (’Round About Midnight) during October 1955, in anticipation of Davis’ imminent departure from Prestige, but, for legal reasons, it couldn’t be released until he had met the terms of his contract with Weinstock’s company.

To meet Weinstock’s demands and hasten his departure, Davis took his group – which had debuted for Prestige with the album Miles: The New Miles Davis Quintet, released in April 1956 – into Rudy Van Gelder’s Hackensack studio, in New Jersey, for two long sessions on May 11 and October 26 of that year. In both instances, the group set up their instruments, then waited for Miles to call out the song titles and cue them in. They went through song after song as if they were playing a live gig, with no second takes (apart from one track, “The Theme”). The music was honest and raw – but also compelling.

Tender lyricism and vulnerability

Workin’ With The Miles Davis Quintet used material from both trips to Van Gelder’s studio, but wasn’t released until December 1959, following its sister albums Cookin’ (released in July 1957) and Relaxin’ (March 1958), which established an album title theme (Steamin’ concluded the series in July 1961).

Workin’ opens with “It Never Entered My Mind,” a Rodgers & Hart show tune that had been covered by Frank Sinatra in 1949 and which Miles first cut for Blue Note five years later. Red Garland’s delicate arpeggios begin the performance; then Davis states the main melody using a muted horn, which imbues his performance with both a tender lyricism and a sense of vulnerability.

John Coltrane is conspicuously absent from the opening cut, but his presence is immediately apparent on the harmonized twin-horn theme to “Four,” a Davis original that he first recorded in 1954 and which stayed in the trumpeter’s repertoire well into the 60s (it was also a favorite of tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins).

Davis uses an open horn on this track. His melodic lines are lean and relaxed in his solo, contrasting with Coltrane’s robust and more intense delivery, which witnesses him firing off long, flowing salvos of notes. Garland follows Coltrane with a solo that highlights both his delicacy and rhythmic felicity (given his sensitive touch, it’s hard to believe that Garland had a brief career as a boxer). Philly Joe Jones also has an opportunity to shine, trading “fours” (alternating four-bar solo sequences) opposite Davis.

Profoundly exploratory

Dave Brubeck’s “In Your Own Sweet Way” finds Miles back using a Harmon mute on his trumpet, bringing a sense of fragility to the gorgeous melody. Chambers and Jones, the band’s engine room, keep the piece swinging, underpinning Coltrane’s lofty tenor saxophone flights with a solid and well-grounded groove.

A brief (it clocks in at just under two minutes) rendition of “The Theme,” used by Miles to close his live shows, leads into a Coltrane composition, “Trane’s Blues.” After enunciating the main theme, the track morphs into a finger-snapping swinger propelled by Chambers’ walking bass and Jones’ ride cymbal. Miles takes the first solo (using an open horn), followed by Coltrane, whose improvisation is profoundly exploratory.

Letting others take center stage

Though Miles Davis was a huge fan of the Ahmad Jamal trio and covered several tunes in the Pittsburgh pianist’s repertoire, he and Coltrane sat out on “Ahmad’s Blues.” Instead, Miles lets the trio of Red Garland, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones take center stage, seemingly replicating the point in his live shows when he and Coltrane took a breather.

In Workin’’s original liner notes, writer Jack Maher also states that Davis was keen for Bob Weinstock to hear what Red Garland could do in a trio setting. Evidently, the producer was impressed by Garland’s sparkling right-hand runs and signed the pianist to a solo deal. The trumpeter wrote in his memoir, Miles: The Autobiography, that he hired Garland because of his stylistic similarities to Jamal: “Because I wanted to find a piano player who played like Ahmad Jamal, I decided to use Red Garland… he had that light touch I wanted on the piano.”

A bona fide jazz superstar

Unlike the rest of Workin’, the Davis-written “Half Nelson” – a song he first recorded as a sideman with Charlie Parker, back at the height of the bebop revolution, in 1947 – originated from the October 26 session, Davis’ final studio appearance for Prestige.

A second, shorter take of “The Theme” (with Philly Joe Jones briefly spotlighted) wraps up Workin’ just as if it were bringing the curtain down on a live set – which is what Davis intended: the music he recorded during his final Prestige sessions documented what his band were doing on stage at the Café Bohemia.

By the time Workin’ hit the shelves, just before Christmas 1959, musically, Miles Davis had moved on and was leading a sextet that had shifted away from hard bop into modal jazz. Thanks to his groundbreaking album Kind Of Blue, released earlier that year, he was now a bona fide jazz superstar whose music had crossed over into the mainstream. But Workin’ was a potent reminder of how important his first great quintet had been in the development of small-group jazz in a post-bebop world.

The 6LP The Legendary Prestige Quintet Sessions box set is out now.