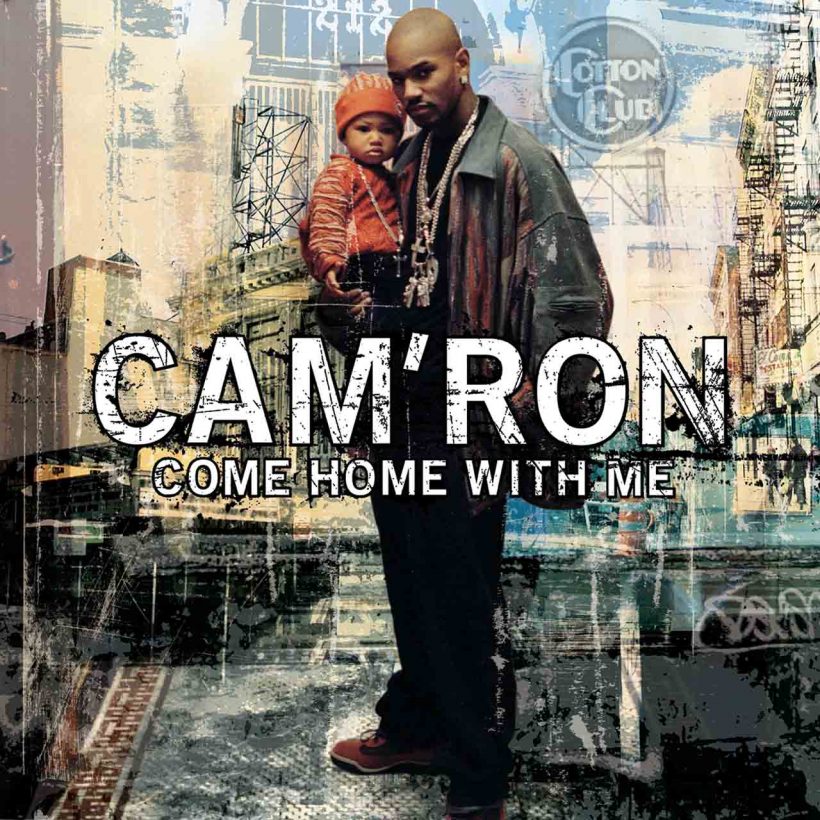

‘Come Home With Me’: Cam’ron’s Breakthrough Hit

The smash record led to Cam’ron’s crew, The Diplomats, taking over NYC.

Cam’ron couldn’t miss. Not again. In the years leading up to 2002’s Come Home With Me, the man who would usher in a new era of New York rap had seen one too many shots fall short. The first was Cam’ron’s missed game-winning three-pointer during the P.S.A.L. championship game at Madison Square Garden, which grazed the rim and altered his career trajectory. His 1998 debut album, Confessions of Fire, yielded a moderately successful single (“Horse & Carriage”) but didn’t make him a commercial or critical diaper dandy. Cam’s grimy sophomore effort, 2000’s S.D.E., detailed his deflated hoop dreams and transition from hustling to rapping while displaying substantial artistic growth, but Epic Records dropped the ball when promoting the record.

Cam’ron was in his mid-20s when S.D.E. only went Gold, virtually middle age in rap years. He had to score with his third album, Come Home With Me. After an acrimonious exit from Epic, he signed with the ascendant Roc-A-Fella Records, the label co-founded by Jay-Z and Cam’s childhood friend, Dame Dash. Cam set up an office in a storage closet, regularly conferenced with label staff, and began recording songs for Come Home with Me with the Diplomats, his crew of Harlem compatriots that included Juelz Santana and Jim Jones.

Listen to Cam’ron’s Come Home With Me on Apple Music or Spotify.

His first major move proved he knew a hit record. The day he and Juelz Santana recorded lead single “Oh Boy,” Cam took it directly to radio station Hot 97. Before the Roc could clear the Rose Royce sample on the beat, “Oh Boy” was blaring in the club and the streets. It remains one of the most successful and enduring street rap crossovers. New York’s answer to Nelly’s “Country Grammar,” the knocking yet glinting instrumental and Cam’s delivery – in conjunction with the high-pitched “boy” sample – underscored lines about speeding in sports cars and belied grimmer lyrics about going to court for selling heroin (aka “boy”). Cam went pop without changing his subject matter or delivery, linking strings of vivid internal rhymes as he punned on the same word/phrase so many times that parsing each meaning of “boy” required undivided attention. That wasn’t a problem, though: The song was so accessible that anyone could bounce and chime in on every “boy” and “oh boy” without thinking.

“Oh Boy” presaged the tone and greatest strengths of Come Home With Me. Throughout the album, Cam’s combination of swagger, wry wit, and inexhaustible wordplay made his lavish material flexes sound fresher than those of his peers while making the harrowing realities of the Harlem drug trade seem both more surreal and even colder. Come Home With Me also signals the moment Cam perfects his invincible head honcho persona, the man calling plays for his partners and grinning a sardonic “Hi hater” to anyone who didn’t show respect. Though jaded by the rap industry and scarred by all that he witnessed growing up, Cam pushed ahead, his flow slower, calmer, and better suited for reflection.

That reflection defines much of Come Home With Me. Many of the songs are memoirs of the Harlem depicted in the collage on the album cover. On “Losing Weight 2,” Cam recalls beefing with rival crews dealing in the same neighborhood. It’s the kind of song that would resonate with The Wire’s Avon Barksdale, the player sending his soldiers to sell on and protect his corners. “Live My Life (Leave Me Alone)” and “Come Home With Me” follow along the same lines, but the latter features some of Cam’s most concise and evocative writing. In two lines, he condenses his life in the early ’90s: “’Cause I ain’t have no fresh clothes/Or jewelry with the X O’s, my house had asbestos.”

Ever the businessman, Cam knew he needed songs that appealed to women. Chief among them is “Hey Ma,” the album’s hit single. The laidback, quasi R&B beat built around a Commodores sample and conversational hook is embedded in the brain of anyone who listened to rap radio in the early 2000’s. Cam is irrepressible as the affable, self-aware player half-heartedly pretending he’ll change his ways. It’s a slight shift in tone from “Daydreaming,” where Cam plays the sensitive, reformed thug who’s trying to make amends and rekindle a former love. (Granted, both stand in stark contrast to the extensive STD PSA “On Fire Tonight” and the cold-blooded macking of “Stop Calling.”)

Come Home With Me codified the sound of New York rap that began with Jay-Z’s The Blueprint the year prior. Just Blaze, Rsonist, a young Kanye West, and the rest of the album’s producers put their singular spin on soulful yet bombastic beats that sounded like a procession of vibrant Escalades mobbing through the projects. It’s a sound The Diplomats would perfect the following year with their debut, Diplomatic Immunity.

On the features front, Come Home With Me is essentially a showcase for Cam’ron’s Diplomats compatriots: Juelz Santana, Freekey Zeekey, and Jim Jones. They all turn in some of the hungriest verses of their respective careers. A wise hustler, Cam played both sides of the fence, affirming his allegiance to Roc-A-Fella by soliciting features from Memphis Bleek and Beanie Sigel on “The Roc (Just Fire).” Despite the behind-the-scenes tension between Cam and Jay-Z, the Roc-A-Fella head delivered the sharp and gloating opening verse on the post-9/11 anthem “Welcome to New York City.”

Come Home With Me went platinum before the end of 2002, catapulting Cam’ron and the Diplomats into the public eye. They eventually became the biggest New York rap collective since Wu-Tang Clan, and Cam’ron proved that he could outshine and outrap many of the Harlem rappers who’d preceded or come up alongside him. Perhaps equally important, Come Home With Me gave Cam the confidence to turn in more linguistically daring records like 2004’s Purple Haze. This is where the legend of Cam’ron begins.

Listen to Cam’ron’s Come Home With Me on Apple Music or Spotify.