‘White Light/White Heat’: How The Velvet Underground Foretold The Future

A decade before punk was even a thing, ‘White Light/White Heat’ found The Velvet Underground light-years ahead of everyone else.

In early 1968, The Velvet Underground uncharacteristically posed, with apparent good humor, for a publicity photo to mark the launch, on January 30 of that year, of their pathologically uncompromising second album, White Light/White Heat. In the most commonly circulated shot, Sterling Morrison, with eyebrows arched, wryly executes a “ta-daaa” gesture towards the LP sleeve; Maureen Tucker stares impassively into the camera lens; John Cale, presciently, is already looking elsewhere; and Lou Reed, inscrutable behind his shades, wears an expression notable only for its outright lack of any discernible emotion.

Listen to White Light/White Heat (Super Deluxe) now.

It would subsequently emerge that Reed was fiercely proud of the album – with every justification. Roundly ignored (or regarded as a wholly alien artifact) at the time of its release, White Light/White Heat not only provided a bracingly harsh audio vérité snapshot of the band’s chaotic circumstances at the time of recording, but also, in its way, foretold the future. The migraine murk of its unglamorous non-production, its contrasting clarity of intent, its murderous performances, and the flinty, unsentimental reportage of Reed’s lyrics ring-fenced it as an obstinate manifesto from which, the best part of a decade later, punk greedily drew style and substance.

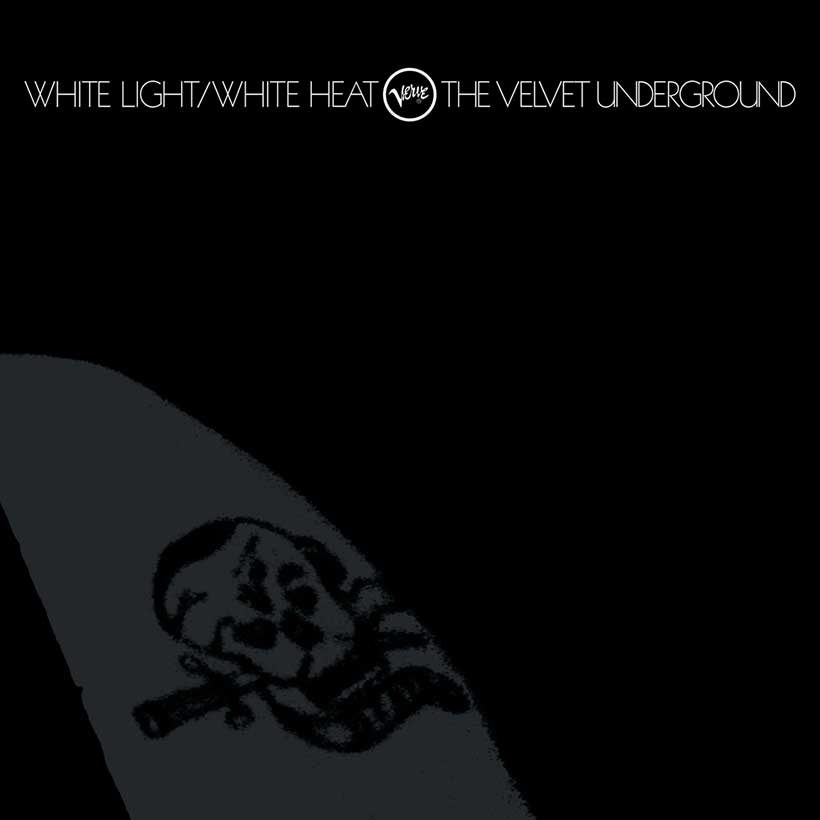

White Light/White Heat’s blunt impact begins with that album cover, portending the music within: a forbidding black-on-black monolith with covertly telling details. The skull tattoo at bottom left is modeled by Joseph Spencer, star of Andy Warhol’s 1967 film Bike Boy. “Death” is emblazoned on the banner beneath the skull, but for all its downer iconography and surly, nihilist content, White Light/White Heat radiates a life-affirming belligerence.

The title track and “I Heard Her Call My Name” are extreme, benchmark recordings: electric music at its most unstable and charged. The former, presented as a deadpan paean to methamphetamine, is a malevolent centrifuge with Cale’s bass right at the front of the mix: the relentless violence of his playing is quite without precedent. Similarly, “I Heard Her Call My Name” is dominated – overwhelmed, even – by Reed’s defiantly unruly lead guitar, popping and shrieking with uncontrolled feedback. Way off in the background, the Velvets stoically churn away like a garage band viewed down the wrong end of a telescope with a dirty lens.

An unrepentant disregard for convention

Both songs conclude with Reed nonchalantly pulling the jackplug from his guitar: a logically direct way to break the circuit and stop the tumult. The unrepentant disregard for conventional notions of proficiency in these livid performances still seems exciting and liberating. “Proper” musicians wouldn’t, and couldn’t, have played like this – and it’s worth remembering that Reed and Cale, coolly literate and fully conversant with avant-garde principles, knew exactly what they were doing.

White Light/White Heat’s reputation as a uniformly rough-hewn blast of dissent fails to take into account the delicate “Here She Comes Now,” a wryly measured interlude, fancifully interpreted in some quarters as a three-way metaphor for sex, drugs, and guitars (“She looks so good… she’s made out of wood”). Consider also that the album’s remaining tracks all deploy a narrative structure, in one form or another. “The Gift” is a bona fide recitation concerning the grisly fate of Waldo Jeffers, who mails himself in a box to his girlfriend. (“She… plunged the long blade through the middle of the package”). This bleak vignette is blandly delivered by John Cale, hard-panned into one speaker while the Velvets grind implacably over a single chord in the other.

“Lady Godiva’s Operation,” meanwhile, woozily transitions from faux-rapt observation (“Dressed in silk, Latin lace, and envy”) to a sinister, unblinking account of a surgical nightmare (“The screams echo up the hall”). In less gnarled hands, its smoky melody could almost qualify as psychedelic. Above all, the 17-minute “Sister Ray,” with its cheerfully dissolute cast of characters (Doc, Sally, Miss Rayon, Cecil, Rosie, Reed’s old fallback “Jim”, and Sister Ray himself/herself), is operatic and orgiastic in its lurid tableau of oral sex and mainlining. And none of this would work half as well without Maureen Tucker’s unperturbed pulse beat. As successive cover versions have proved, standard rock drumming somehow diminishes these songs.

It may have taken years to gain traction, but nothing would ever be the same after White Light/White Heat – not least the Velvets, following Cale’s enforced departure in autumn 1968. It’s one of a precious handful of albums that helped rock music turn a significant corner… before dragging it down an alley and beating sense into it.

Neil Saunders

February 5, 2019 at 3:19 pm

Why must punk – a vastly overrated movement – always be invoked? It’s like the Mormons baptising those they claim as their ancestors.